Shipwrights have always possessed space within our stories. How many of us grew up with the fable of Noah, the ark-builder destined to save humanity? Others of us probably heard tales of Manu, king of Dravida, who built a boat to ferry the Vedas safely during a great flood. Others still learned of Jason’s adventures on the Argo, or of the sons of Ivadi who crafted Skidbladnir, or even Nu’u, who landed his vessel on the top of Mauna Kea on Hawaii’s Big Island after a great flood. Many myths characterize shipbuilders as beacons of hope, harbingers of change, and men who possess a unique—and often divine—vision of the future. These ideals have been passed down from ancient archetypes into our current works of science fiction and fantasy.

Shipwrights, much like the people who captain ships, are seekers of something new and different in the world. One of the differences, however, is that shipwrights have only heard stories of what that new land could be, and they are the ones who must first take the risk of saying, “What if?” Shipwrights not only act on the faith they have in a better, stranger future, they act on the questions that inhabit their lives. This is an act of rebellion. There is something at home that is not satisfactory. In each version of the story, in each embodiment of the archetype, there is an understanding that the world as it is is not enough. The shipwright sees this and decides to do something about it. There is an inherent and deep-seated hopefulness to the shipwright, who sits at their desk, or prays their altar, or works at the boat yard, and dreams of a different world.

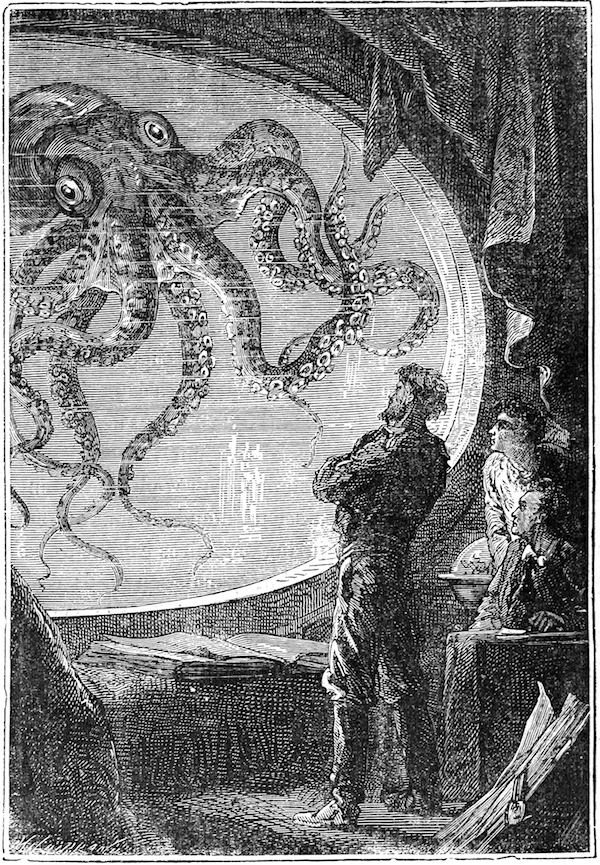

In the late nineteenth century, the science fiction as a genre was starting to gain recognition. Shipwrights, in addition to sea captains, were appearing at the forefront of literature as visionaries and pioneers. One of the best examples from this time is Captain Nemo, architect and captain of the Nautilus in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Verne sets up a familiar character; a man crushed under the thumb of modern society who is eager to be free from the burdens of the modern world. Equal parts separatist and idealist, Captain Nemo defines the shipwright in science fiction for the next few decades with his tortured genius, visionary drive, and his faith in his own creation. (The Nautilus itself becomes a standard in science fiction as well, with comparisons drawn between it and other late 19th century speculative ships, Thunder Child from H.G.Wells’ War of the Worlds and the Astronaut from Across the Zodiac.) Nemo gracefully, madly inhabits the archetype. He is a revolutionary who selects a chosen few to journey with him; a new, modern Noah, saving two of every animal in his archives and journals, ferrying them away from the backwards mainland into the idealized future.

Nemo, unlike the rest of the shipwrights mentioned in this essay, does not ascribe to a divine directive in order to find his moral grounding. Stated to be the son of an Indian raja and implied to be Sikh, Nemo is a man with a vendetta against British imperialism and colonization. This could come from Verne’s own perspective as a Frenchman, whose nation had seen the fall of the Sun-King-descendant emperor, and had then invaded Mexico, China’s Forbidden City, and Russia immediately after. Nemo rejects god in favor of science, dedicating his life to the furtherance of his research and exploration, even at the cost of his own life. Science, not god, is the focus of his faith, and he believes that one day his work will benefit all of humanity. Parallels can be drawn here to the mythic Manu, who built a ship to protect the Hindu holy texts during a great flood. If Nemo is Manu, he has built a religion out of research on The Nautilus, and uses his skills to preserve his texts until the world is ready to receive them.

In the mid-1900s, shipwrights come to the forefront of major works of fantasy. Both C.S. Lewis, with The Chronicles of Narnia, and JRR Tolkien, penning Lord of the Rings, showcase shipwrights in all their archetypal glory. In Narnia, Prince Caspian oversees the building of The Dawn Treader, a ship designed to sail across the ocean on a mission to save his land from destruction. In The Silmarillion, Earendil builds The Vingilot to travel to Valinor, the home of the gods, on behalf of Middle-earth, seeking help against an invading army.

There are interesting manifestations of the original archetypal depictions within the stories of The Dawn Treader and The Vingilot. Both ships are destined towards a divine land (Aslan’s Land in the Chronicles, the Undying Lands in The Silmarillion), both shipwrights sail as representatives of their people, and ultimately, both men find their gods, deliver saviors to their people, living afterwards in the shadows of their journey, which has long-lasting implications and effects within the mythology of their respective series. In these works, both Caspian and Earendil are working towards the betterment of the community, not the individual. This is a common thread throughout modern and mythic ship builders as they take on tasks for the sake of the collective, bearing the burdens of their homeland’s expectations.

Like Nemo, both shipwrights rebel against the traditional assumptions of their cultures. Caspian and Earendil have seen their world in danger and they believe that the way to save themselves is through divine intervention. However, instead of rejecting God as Nemo did, Caspian and Earendil act with an extreme, desperate faith in the divine as they build their ships and plan their journeys. They are more like the original mythical shipwrights, who act on the words of God, regardless of the opinion of others. Neither Casspian nor Erendil know if they will find Aslan or the Valar, but they venture forth despite not knowing.

With no guarantee of success, both must have known that within each journey was possibility, even an obligation, to sacrifice oneself for the sake of the journey and the furtherance of the community. Like Nemo, they are willing to die for their causes, and both offer at some points to never return from their journeys. Both Caspian and Earendil are charismatic enough to convince others to go with them, and they found among their people fellow faithful, others who were willing to put their lives on the line not only for their futures, but for the shipwrights themselves.

Buy the Book

Fate of the Fallen

Both Caspian and Earendil find the land of their gods, but there are complications. Caspian finds the fallen star-king Ramandu and is told that he will have to travel to the edge of the world and sacrifice a member of his crew. Although Caspian intends to sacrifice himself, when the Dawn Treader can go no further Caspian agrees that he must stay behind with the ship. He can’t leave The Dawn Treader to travel back to Narnia without him, and he accepts that it’s his destiny to make that return journey. This is a direct reference to the Irish mythological story device, the immram, where the new Christian faithful journey to the land of the gods and return to serve their country with the benefit of sainthood and new revelations about their God and their faith.

J.R.R. Tolkien as well knew of the immram, composing a poem of the same name, and using the same devices with Earendil’s journey on The Vingilot. However the difference between Caspian and Earendil is that Earendil is forbidden to return home. He has seen the divine of the Grey Lands, and he has been changed. He is not allowed to bring back the news of his journey, but must again trust that when he is needed he will be called. The stars seen in the Voyage of the Dawn Treader make their own appearance here, as the Silmaril, the light of the Valar, is given to Earendil, who places it on the bow of The Vingilot to guide the way. Earedil then sails upward, to the stars themselves, and places himself in the celestial zodiac, where The Vingilot and the Silmaril becomes the North Star, the light of the elves, constantly guiding and protecting the elves on Middle-earth.

In modern and contemporary fiction, shipwrights are often depicted as spaceship designers. They look up into the night sky and imagine how to get human beings from Earth to Mars, or Jupiter, or beyond. Modern works of science fiction show these people to be ambitious and experimental, obsessed with the preservation of their cargo and the spirit of exploration that has possessed shipwrights the world over. They continue to work towards collective futures, but the individual space-shipwright is eschewed for the corporation or military, and rarely does a character rise to prominence as a spaceship designer.

While the current emphasis is less on divine directive and more on the inescapable call of the unknown and unexplored, there are still examples of hopeful, faithful, forward-thinking shipwrights in modern science fiction and fantasy. The building of a ship to take humanity to the next level of understanding remains the first step in a journey of faith that continues to define major instances of important shipwrights throughout contemporary works.

A fascinating example of faith in modern shipwrights are the fictionalized Mormons from The Expanse. A series of sci-fi novels and short stories, the world of The Expanse focuses on the struggles of a colonized solar system that lacks Faster-Than-Lightspeed (FTL) travel, with later stories exploring what happens when FTL travel is achieved. Wanting to pursue religious freedom, the Mormons designed and built a ship to take them to Tau Ceti where they planned to pursue a separatist existence. The Mormons were not able to realize this, as they had their ship commandeered, but they did build it for the express purpose of saving their culture and pursuing their faith. An inherently rebellious act, the Mormons looked at the world they were living in and rejected it, believing that they could find a better way in a better land.

Looking to contemporary fantasy, we have Floki, from Vikings (The History Channel, 2013), who was intimated to have a divine connection throughout the series that is considered both insightful and mad. He designs a longship that will allow the raiders to sail both across oceans and up rivers, making them more dangerous and more mobile than ever before, reflecting many of the tropes established by Captain Nemo—a man inherently mad, a man on the edge of sanity, but also greatness. The longship he designs also allows Floki to travel west, searching for Asgard, the mythical land of the Norse gods. He eventually lands on Iceland and believes his journey to be successful, founding a small settlement there and making an attempt to live there in peace. His faith pulls him through the series, and while his end is a particularly ironic twist on the trope, Floki also asks that others put their faith in him, assuring Ragnar and other vikings that the ships will carry them across the wide sea, to a land of riches and plenty.

King Brandon Stark, called the Shipwright, was only briefly mentioned in George R.R. Martin’s A Clash of Kings, but his story is exceptionally archetypal. Brandon sailed west, towards a land of plenty, a land without death or (even worse, for a Stark) winter. He never returned. But, like all shipwrights, all men who take up lathe and stone and work the wood to travel the ocean, he had faith that there existed a better place and a chance for a safer, more bountiful future for his people.

There are a few themes here, right? A man, typically royal, spiritually inclined, and intent on making a better life for his chosen people, sails west (usually, but sometimes east), into the setting sun. They typically never find exactly what they were expecting, and only a few return. Most are revered, some are reviled, but all are remembered. There’s a latent desire for a better future, a new life. There’s little attachment to the current state of the world or country from which each shipwright descends. Answers are not at home; answers are in the lands of the gods, the Grey Lands, the expanse of space.

Throughout fiction, ships are symbols of both change and hope, but when built, first built, ships also represent cultural dissatisfaction and disillusionment. Whatever is here is not as good as what is there. These characters; Nemo, Earendil, Floki, and so many others, represent a very human desire to strive for better in their lives and their communities. Science fiction and fantasy authors have always imagined a future, or a past, or a present that is different. Authors use characters like shipwrights to communicate their own desire for change. Within the genre, authors work to craft stories on speculation and faith in the future, building ships and writing books that will allow readers to set sail, to find new ideals for the next generation, and to present us with an alternative for a larger, better, more visionary future.

Shipwrights and science fiction and fantasy authors always seek something different, imagining a new world, often a better, mythical world of safety and comfort. Shipwrights do not languish on the edge of the shore. They craft a vessel out of faith and trust, creating a physical embodiment of a new direction, the vessels of the collective, the people, and the future. The speculation, the inspiration, the new imaginings–shipwrights and authors set out in faith and with a hopeful vision, casting off shore to find a divine land, not for themselves, but for everyone.

Linda H. Codega is an avid reader, writer, and fan. They specialize in media critique and fandom and they are also a short story author and screenwriter. Inspired by magical realism, comic books, the silver screen, and social activism, their writing reflects an innate curiosity and a deep caring and investment in media, fandom, and the intersection of social justice and pop culture.