Is there a perfect time to read a given book? A moment not too early or too late, where you’re not too young or too grown—not to mention not too tired, worn out, beaten down by the world, or too excitable and distracted and enthused about other things? What about a perfect place?

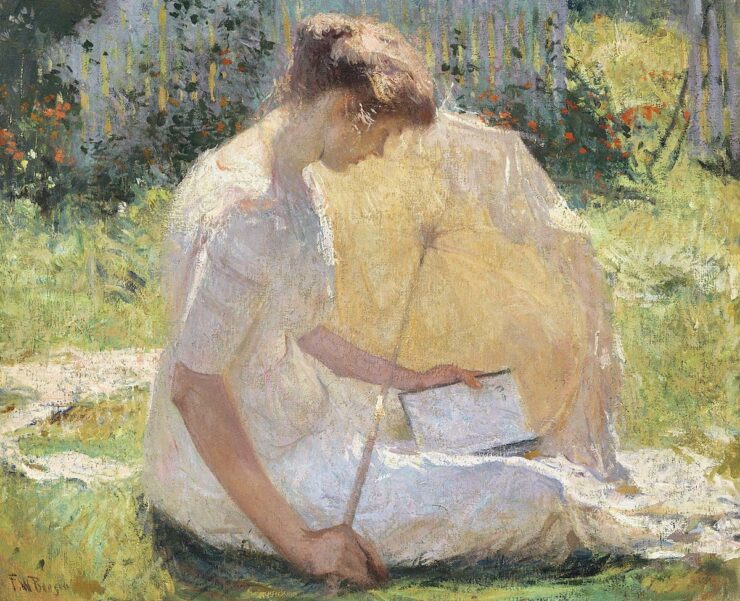

The experience of reading a book at what feels like precisely the right time and in just the right place can probably be had deliberately, but as often as not is a matter of chance. I read Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lavinia on a train, on deadline for a review, before trains had wifi. In my memory it was a gloomy day, so there was nothing, not even scenery, to distract me. The rhythm of the train propelled my reading, but also connected with it, so that I always think of that book with movement and focus.

That was an unexpected blessing of place. But when I think of the ideal window of reading opportunity, I mostly think of time, which is another way of saying context: How much have you lived? What are you bringing to the book, and what is it bringing fresh to you? Where are you meeting each other, in the stages of your relative existence?

For some books and readers, this window never closes. But for others, it sure feels like it does.

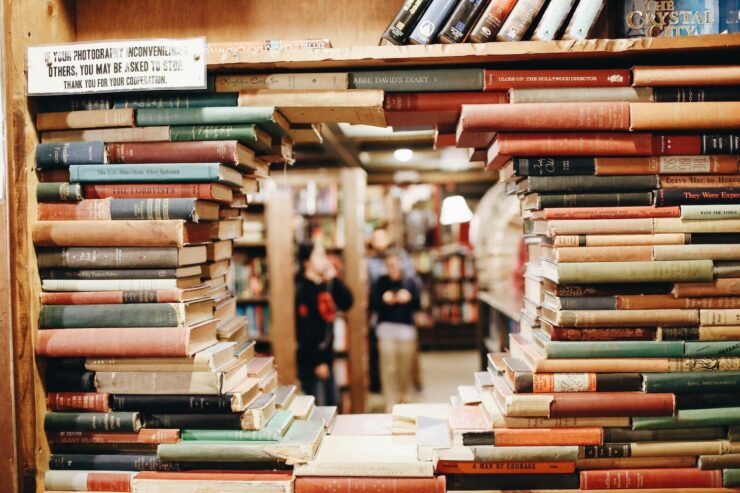

As a teen, I did very little other than read. (Rural Oregon offered few options.) I read great books, mediocre books, books I didn’t fully understand, books I wanted to understand, books I brought home from the mall bookstore and books my mother had bought decades earlier. Going back to some of those books is a well of surprises: I remembered nothing of the plot of Elizabeth A. Lynn’s The Sardonyx Net, only that I had been so upset by the scene in which a girl burns to death that I am, to this day, excessively afraid of fire. I loved Kathleen Sky’s Witchdame so deeply, for its mopey dragon and determined but not particularly special princess, yet I also totally missed some wild details of the ritual of that princess’s coronation. As a kid, Patricia A. McKillip’s The Forgotten Beasts of Eld just read like a dream—I too wanted to live in the woods with a host of magical creatures and piles of books. But re-reading it as an adult, I saw another side, a story about compromise and freedom.

These were entirely different books when I reread them years later. What I saw and what I didn’t notice was entirely different from book to book, and sometimes unpredictable. Maybe I read those books “too early,” in that I didn’t understand parts of them, but if I hadn’t, then I wouldn’t have the specific experience of rereading them, decades later, and finding so much more. You never read the same book twice—but you also can’t have the specific pleasure of rereading without enough time and distance to ensure the experience is something new.

But some of the novels I loved in that era, I’ve never wanted to go back to. It feels like the window is closed, or at least closing. Can anyone read Tom Robbins’ Still Life With Woodpecker the way an oblivious 16-year-old, hungry for all the peculiar experiences of the world, can read it? If I go back to the very first Heralds of Valdemar books, will I change the way I felt about them as a horse-mad, lonely kid? Is that window closed?

If a window really closes, the trick is not to let it change what a book was to you. If you loved a book once, because of the person you were and the book it was, it’s important to respect that, to accept that your younger self didn’t know about an author’s hateful views or their dark personal history. It used to be common to read from a place of ignorance when it came to the writers behind the work. All we knew was whatever the back cover told us. Now that we know so much more—now that authors have to have personal brands, Twitter presences, personal essays about their own favorite books—it changes the context. But what you got from those books, you still got. Those reading experiences are still yours. Knowledge can change what you bring to a book now, but not how you read it the first time.

The window can narrow in other ways, too, ways that are not specific to a book, but to what you’ve been reading. Sometimes I think I can’t take another fantasy about the Most Special Person, the only one who can save the world, especially if they are royalty or have a magic power no one else has. I’ve been reading these stories for as long as I can remember, but they rarely work the same magic they used to. It’s like I’ve met my personal quota on that front, and need to take a break until I’ve read an equal number of other kinds of stories: stories about communities working together; stories about smaller, more personal stakes; stories about how people make their fates, free of destiny and prophecy.

(But books about those Most Special Ones will still sneak in and surprise me.)

The right place to read a book is both simpler and more elusive. It can be anywhere: a favorite chair, a favorite coffeeshop, a long flight. (I read Chuck Wendig’s Wanderers on a plane, which kind of felt like a mistake—it elevated the stress!—but it was so propulsive I simply couldn’t make myself stop.) When you’re a kid, where you read is entirely determined by your parents: maybe it’s in bed, maybe it’s in the book-lined hallway of a boring party attended only by boring grownups.

Mostly, it doesn’t matter. You fall into the book and you’re there, not here. But there are books that want to be read outside (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, How to Do Nothing); books that want to be read at night (I like to read Expanse books when it’s dark out and I can see the night sky); books for road trips and books for vacations and books for reading in little snippets on your lunch break rather than in big gulps. Some books want to be read when you’re alone, and with others it’s almost necessary to have company. At seventeen, I read Jurassic Park in one long sitting in the corner of a beloved cafe. I can’t say I necessarily recommend this—but I also can’t pass that corner without remembering the delight of just not stopping, getting refill after refill, turning page after page, pausing to look up only when trains rattled past on the nearby track.

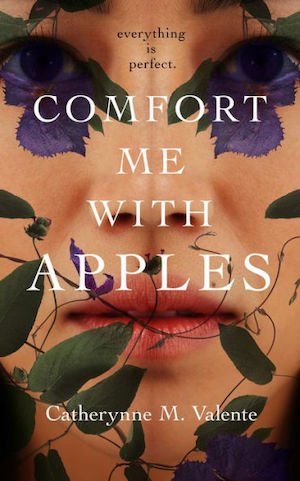

Buy the Book

Comfort Me With Apples

Reading a book in the city where it’s set is one particular joy; reading in contrast is another. I re-read American Gods while traveling in Australia, thinking about what a strange country I’d left behind. It felt different, there. I read Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle on that same trip, in tiny stolen moments, and I still think of it in fits and starts, a book made up entirely of flashes of story and image (and cats, and wells). But this kind of reading-in-place is a privilege, depends on your location, and feels like something of a different era, right now. Now I’m more likely to pick a book in hopes the book will transport me to a different place on its own—a planet of the Culture, maybe. A great city watched over by an N.K. Jemisin character.

Now, finding the ideal reading window is a matter of balancing so many more elements. Do you want to know the author’s life story, to read intense Q&As and their thoughts on craft? Do you want to go in as blank as possible, intrigued by a plot summary and avoiding anything else that might cross your screen? Is it even possible to be aware of hype without being affected by it?

For some, that perfect window is simply as early as possible, before anyone else’s opinion has a chance to color your own. And there is joy in the early read, in being able to tell your reading friends that yes, that book is just as good as promised, or warn them about some detail that may make it a bumpy read for them. For others, it’s armed with as much knowledge as possible about the book, its creation, its inspiration, the playlist the author had on while writing. For others, none of that even registers. The book is what’s on the page, nothing more. (I want to know what it’s like inside their heads.)

This isn’t just about how there’s no perfect time to read a book, no spell to get it just right, no process to hone. It’s also about how you change the book, the way you might think more about the mentor characters than the sprightly heroines as you get older, or how you’ll see the way an author worked in climate change where you never saw it before. The books we read when we were young have all kinds of new things to offer; the ones we read now will too, decades on. The best books keep the window open for you.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.