The movie Titanic begins with an elderly Rose telling the story of her voyage across the Atlantic. As we push in on her eyes, we suddenly find ourselves in 1912, and the movie begins in earnest. Only a few times during the film do we return to the elderly Rose to touch in on her experience—but the movie ends there, just as it began. In storytelling, this is known as a framing device: a story told within the context of another story. Framing devices can be very simple, or very complex, as we’ll see in a moment. In every case, the framing device is a gateway that sets the stage for a deeper journey into story.

Framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves. Many of the earliest recorded stories—such as The Ramayana, The Mahabharta, and The Odyssey—were told by an in-book narrator. Frame stories glue together collections such as The Canterbury Tales and the Arabian Nights, and set the stage for comparatively recent tales such as Wuthering Heights. Shakespeare used a “play within a play” to imply that Hamlet knew of his uncle’s murderous guilt. Framing devices appear in modern literature as well—such as in Patrick Rothfuss’ mega-popular The Name of the Wind, in which Kvothe tells stories from his past even as new events unfold in his present.

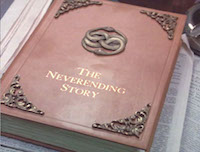

Naturally, framing devices have found their way into movies and TV shows as well. Classic films with framing devices include The Princess Bride (told by Peter Falk to Fred Savage, with the narrative reversing and changing course when the two characters disagree on the tale’s direction), and The Neverending Story (a book within a movie, the twist being that the main character “enters” the book). More recent films with framing devices include Life of Pi (a white lie told to a journalist) and Slumdog Millionaire (a confession at a police station). On TV, How I Met Your Mother has a framing device implied by the title, and LOST featured a unique structure that included flashbacks, flash forwards, and flashes in other directions in almost every episode. These are just examples; dozens of shows and movies use similar devices. Framing devices are absolutely everywhere.

But where frame stories get really interesting is when they start being stacked up: stories within stories within stories. One of the best examples is the eighth volume of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman (which I recently discussed at length), entitled “World’s End.” Modeled after The Canterbury Tales, this story features a group of travelers trapped at an inn between worlds, going around a table telling stories. The storytelling peaks with the issue “Cerements,” in which the character of Petrefax tells the tale of a sky burial at which several corpse-handlers sit around telling stories of their own. One of those stories is the tale of a student’s apprenticeship to the Mistress Veltis, who in the story tells her own story about how she lost her hand to a magic book. You follow all that? That’s four layers of nested storytelling—all within the greater story arc of the Dream King.

Another great example is Inception, in which Leonardo DiCaprio enters Cillian Murphy’s dream to implant an idea in his subconscious. In the dream, DiCaprio puts Murphy to sleep, following him into a second layer of dreaming which soon gives way to a third—the catch being that time passes ever slower within each nested dream. In the innermost dream, Leo gets knocked out and enters “limbo”—an endless dream that could conceivably last for eternity while only seconds pass in the real world. After what seems like years, Leonardo finally wakes through each successive dream layer, returning (we think) to his real, waking life. For those keeping score, that’s five layers of nested story.

As an aside: Christopher Nolan may have been inspired by two classic episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation that both involve frame stories. In “Frame of Mind,” Commander Riker finds himself performing in a play in which he’s a patient in a psych ward—only, the ward becomes real, and his doctors tell him he’s crazy. At the episode’s climax, reality shatters, and Riker discovers he was trapped in a dream within a dream. In “The Inner Light,” Captain Picard gets zapped by a satellite and lives forty years of another man’s life on a faraway planet. He becomes a father and a grandfather and ultimately forgets his old life—until, as he lay dying, the entire experience is revealed as a kind of experiential history book. When he finally wakes up, only forty-five minutes have passed on the Enterprise. Both of these episodes feature framing device motifs that show up in Inception.

As an aside: Christopher Nolan may have been inspired by two classic episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation that both involve frame stories. In “Frame of Mind,” Commander Riker finds himself performing in a play in which he’s a patient in a psych ward—only, the ward becomes real, and his doctors tell him he’s crazy. At the episode’s climax, reality shatters, and Riker discovers he was trapped in a dream within a dream. In “The Inner Light,” Captain Picard gets zapped by a satellite and lives forty years of another man’s life on a faraway planet. He becomes a father and a grandfather and ultimately forgets his old life—until, as he lay dying, the entire experience is revealed as a kind of experiential history book. When he finally wakes up, only forty-five minutes have passed on the Enterprise. Both of these episodes feature framing device motifs that show up in Inception.

In David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, six different tales are nested inside each other like Russian dolls (This is not true of the movie adaptation, which I recently reviewed.) The first is “The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing,” in which the main character embarks on a journey across the Pacific in 1850. The author cuts the story off halfway (literally midsentence!) to begin a second tale, this one set in 1931 and following the character of Robert Frobisher—who, it turns out, is reading Ewing’s journal. Frobisher’s tale is itself cut off to begin a story set in 1975—and onward it goes, each new story set further in the future, each new character reading the text of the previous tale. Only once the sixth story concludes does Mitchell unwind it all, telling the second half of each tale in reverse chronological order and ending where it all began. At six layers deep, Cloud Atlas might just be the most complex framing device ever created. (If it’s not, I’d love to know what is…)

These examples are complex, but they raise a simple question: why do framing devices work so well? Perhaps it has to do with the simple idea of suspension of disbelief. As readers and viewers, we have to suspend our knowledge that fiction is fake when we read a book or see a movie. That’s how we’re able to “get into” the experience. But when we experience a story within a story, that transition is more natural. It’s as if once we make that first leap of the imagination, we get more easily swept away with each new layer.

And when it all ends… we find ourselves back in the first frame, often surprised to remember where it all began. That moment can be powerful, and speaks to the intoxicating power of a well-told story. Perhaps that’s why framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves.

And when it all ends… we find ourselves back in the first frame, often surprised to remember where it all began. That moment can be powerful, and speaks to the intoxicating power of a well-told story. Perhaps that’s why framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves.

Anyway, that’s a brief look at stories within stories within stories. Next week we’ll take the whole thing interactive and explore some games within games within games. Stay tuned…

Brad Kane writes for and about the entertainment industry, focusing on storytelling in movies, TV, games, and more. If you enjoyed this article, you can follow him on Twitter, like Story Worlds on Facebook, or check out his website which archives the Story Worlds series.

I will admit I have a huge weakness for stories told with framing devices. I absolutely love love love the Kingkiller Chronicles, and just about every other item you listed. I really enjoyed the Cloud Atlas movie, even though it’s “frame” wasn’t as clear cut. I also tend to like narrators when done right – Lemony Snicket is great, and Ewen narrating/writing his story in the Moulin Rouge movie is another great example.

Basically for me I think it comes down to the very clever things that can be done with the frame – whether it’s advancing the story or providing small clues and foreshadowing–all the narative devices that I love to see.

One of my favourites is /Turn of the Screw/ because the framing allows for so much ambiguity in what is happening and how to interpret the events. I think that it is three or four layers deep.

Frankenstein is a good one. At one point you have:

1. A letter from an Arctic explorer, Robert Walton, to his sister, telling her

2. The story Walton heard from Victor Frankenstein, which includes

3. The story Victor heard from the monster, which includes

4. The life stories of the cottagers who shelter him.

And I suppose you could add:

0. The preface, in which Mary Shelley tells the story of how she came to write the rest of the novel!

Nice list!

I think my first experience with one of these framing devices was “The Neverending Story” by Michael Ende, mentioned in its movie incarnation here

Reading a book about a character reading a book who ends up inside his book – as a child I loved it! Still do :) The book also adds a lot more to Bastian’s adventures including the consequences for him travelling within the story

One little thing about the Worlds’ End story party: Another of Mistress Veltis’ stories (retold by Master Hermas (retold by Petrefax (retold by Tucker, in the end))) is a story about Petrefax’ own visit at the inn in the future. One wonders how much she told of the stories told in that story, particularly the one with herself in it.

The Wind Through the Keyhole was a great example of a three deep nested story. Really well done (and allowed us to live a little bit longer with Roland and friends).

Catherynne M. Valente’s The Orphan’s Tales are, in short, fantasy Arabian Nights. I have not tried to count the maximum “nesting score”, but would not be very surpised if it would be more then 6.

Yeah, I was just going to mention that I think the most nested narrative I can recall reading has been Valente’s The Orphan’s Tales; at some points, it becomes difficult to recall just how far out from the original frame we’ve gone.

No examination of this subject is complete without mention of The Orphan’s Tales; thanks, Spriggana. Maybe it actually backtracked out of recursion levels more than I remember, but I would place my estimate of its highest nesting level closer to 30 or 40.

@chaosprime – I would not go as far as 30, but it is hard to keep count as the various stories interconnect. Still, the wikipedia entry Story within a story claims that in the OT the count is sometimes up to more than seven layers.

The same article also mentions – among many other works – Jan Potocki’s The Manuscript Found in Saragossa with stories-within-stories reaching several levels of depth.

When I think frame/next, I now think Kvothe.

Also Robin Hobbs – Assassin’s Apprentice series. Simple one level nest, as decrepit Fitz tells the tale. Sequel trilogy (Tawny Man) moves ahead without nesting.

Isn’t Proust the most famous frame/nest of all? Bites into a fruit and memories wash over him in Remembrance of Things Past?

I suspect framing devices were invented by writers who got told by pompous editors or “writing teachers,” “You should not tell a story in the first person.” “Hey, I’m not!”

Didn’t realize that those were around back in Homer’s day.

(end)

A famous horror tale that’s a set of nested stories is H. P. Lovecraft’s Call of Cthulhu. Everytime I read it, I’m amazed at how interwoven the tale is and yet, even the first time I read it, I’ve never gotten lost or confused. It’s a master example of this sort of story telling.

The above was meant to end with end(tongue in cheek).

Don’t forget L. Ron Hubbard’s gargantuan series, “Mission Earth.” Before I ever heard the word Scientology, I did actually read that 10 book series and I liked most of it. In “Mission Earth” the story is told by the villain, as a confession to his crimes which make up the story. Further, Hubbard saw fit to include another framework periodically, in the form of a translation device, which has been assigned the task of translating the confession into the fictitious language called “English” in case anyone from Earth involved (the court maintains even the planet is a total fabrication) should be prosecuted and need to reference the testimony.

“The Menelaiad”, one of the stories in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse, has 7 layers of nested storytelling, moving rapidly up and down levels (including one exclamation that occurs in all 7 levels at once). Unsurprisingly, Barth is a huge fan of the Arabian Nights, and layers of storytelling open like trapdoors in almost all of his works.

I would have loved to see Catherynne M. Valente’s The Orphan’s Tales mentioned, as she takes the framed narrative and refines it to such an intricate and heart-achingly beautiful tapestry of interwoven stories. I think there absolutely must be a recursive pattern in her tales, but the sheer amount of time and energy one would have to expend to unravel and itemize each thread of the tale is seriously daunting. If I were stranded on a deserted island, I would be taking The Orphan’s Tales specifically so I could complete that task.

Hey, you know who’s really good at taking framing devices in unexpected directions? Grant Morrison. Take The Filth, which is the story of secret police officer Ned Slade who gets lost in his deep cover personality Greg Feely, and the story of office drone Greg Feely who develops a nervous breakdown and halucinates being Ned Slade, and the story of Ned/Greg having a bardo experience at the moment of his death of a drug overdose, and the story of a god breaking into the world in the form of a gargantuan hand holding a pen, the ink of which brings to life several fictions, including Ned/Greg. It’s all of those things at the same time, in a chaotic, amorphous, incestuous, self-generating hive of stories. Which of course also serve as a frame around the story of the comic book superhero Secret Original, who broke through the sky and ended up in the comic’s world, inside and outside of a comic book at the same time.

It’s wonderful.

I always liked framing. It has largely gone out of style these days, but some of my favorite stories and books use this device.

Having just slogged through it but still finding it worthwhile – William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land. Which became an inspiration for Greg Bear’s City at the End of Time. Also as I mention in my linked Goodreads review, it was likely the first mover for several SF&F/horror concepts now common.

What’s quite fascinating about its framing story is that the frame itself, though allegedly “present day” in its first-person narration, was set back linguistically and perhaps culturally about 100-200 years prior. So as soon as you start reading, you’re already taken out of your own time and reference, before its jump to the far future within the frame.

You conclude this piece by asking why framing devices work so well. I have a simple answer: they don’t. A framing device will not make a bad story better. Many of the examples you cited are classics of literature, such as Homer and Shakespeare. They aren’t great because of the framing devices. These devices are just an element that adds one piece to magnificent and profound works.

You also mentioned Inception. Yes it has dreams within dreams, but it was still a lousy story. Besides, the dreams within dreams weren’t even frames. Each dream did not lead to a new story. It was just the next step in the journey.

Also, Don Quixote employs a classic framing device as well, and features numerous stories within stories.

And remember “In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu) by Marcel Proust that it starts and ends between eating a madeleine.

Framing devices tend to be a turn-off for me. I find they’re a huge hazard to momentum, and often to immersion. Most often, they simply feel like administrivia that must be *got through* before I get to the good stuff.

The Name of the Wind: The book begins with tired old fantasy cliches that I deeply adore – elements that match up nicely with my mental Platonic Ideal of epic fantasy. The first chapter or two gave me *chills* reading it – it made me go Yes! A fantasy author who’s coming from the same narrative place I am, who is likely going to know where all my narrative nerves are! … Nope. Framing device. I got about halfway through the book, then dropped it.

The Odyssey: I loved, *loved* the Iliad. But I’ve never made it through the Odyssey, across multiple reading attempts. It’s about *momentum*, and it’s about continuity of the journey. For me, the Odyssey reads like Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” played on random.

Slumdog Millionaire: I cringed every time they cut away from one narrative thread, to bring us another. I kind of adored the main character, and I adored the story they were ultimately telling, but augh, it was maddening.

It can work, but it’s like shooting for the moon in a game of Hearts – if you fail, you lose big. The framing device in the Ramayana has the decency to wear a big neon “I AM A PREFACE” sign, and stays out of the way once the story starts, and The Princess Bride is very deft, clever, and quick with its framing device.

Another work that does work for me is Bernard Cornwell’s Warlord Trilogy (“The Winter King”, “Enemy of God”, “Excalibur”). You have the aging monk Derfel, writing out a first-hand account of the deeds of King Arthur, for the benefit of a starry-eyed young queen who’s grown up with a much-romanticized version.

One of my favorite heavily-framed stories is Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer, written a couple years after Frankenstein. It’s been a while since I’ve read it, but I think I remember counting eight or ten layers of frames at one point. It pulls stuff like having a book within a book where a person is telling a story in which he encounters a letter in which someone tells a story in which someone tells a story, etc. Somehow it manages (imo) to never get boring or hard to keep track of.

wait, is “the princess bride” listed? i’m too drunk to read

The movie which has a framing device is “The Lego Movie.” The way the framing device is used in this master piece is by starting off with a normal life of a Lego called Emmet. Soon later in the movie he gets involved with a group called the piece of resistance which are trying to stop the end of their happy Lego world from a villian who wants to make everything organized and perfect. Later after trying to defeat the villian, the movie gets to a point where the hero is about to die, and here comes the framing device. All of a sudden it goes to the human world and meeting the business obsessed father of the little boy who has been playing with Emmet and his friends all this time and it ends up that he was creating their story. It plays that both the father and the little boy have been on the Lego level Emmet and Lord Business. So the framing device is that the human boy has been telling the story of the Lego world. Soon ends up that the boy is suppo

sed to be resembling the Lego Emmet and the father the villian, so it end up that the Legos were controlled by the humans. In my theory I believe the reason the filmmakers used this to show that spend more time with your family than to be stuck in a room all the time.

The Lord of the Rings has a nice doubly nested frame. The Prologue sets up the entire story as a translation & adaptation of notes compiled by the story’s participants and various lore masters. (It seems a number of readers skip the Prologue, perhaps that’s why no one else has mentioned it on this thread?) The conceit is used cleverly to explain the background of the revisions made to The Hobbit necessary to retcon it into the larger story, and sets up the appendices and later books (The Silmarillion, etc.) as natural extensions.

Personal recommendation for The House of Leaves by Mark Z Danielewski

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Leaves [spoilers!]

I’m still not entirely sure of 100% of whats going on, but it starts with ‘found footage’ frightened scribblings and goes from there.

the movie i choose with a framing device is “The Book of Life”. the framing device is the book with the girl narrating it to tell a story.