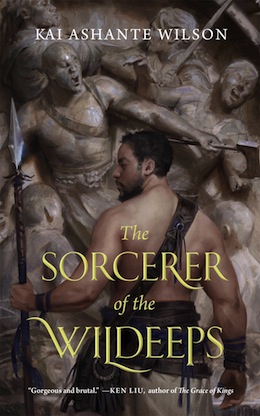

Kai Ashante Wilson’s The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps is, if you haven’t been paying attention, the very first novella to emerge from Tor.com Publishing. As to be expected from the author of “The Devil in America,” it’s complex, powerfully written piece of work, with an ending whose ambiguity only adds to its curious impact.

I say novella—but let’s be honest, the ARC I have clocks in at 208 pages. We’re really talking something closer to a short novel. And Kai Ashante Wilson has packed those pages with the worldbuilding of a much longer work. The world of The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps feels big. It feels deep. It feels like we’ve barely scratched the surface: There’s as much depth of field here as there is in many trilogies, for all that the narration stays tightly focused on one character.

I want to be articulately effusive about this novella. I’m not sure I can be: It’s a little orthogonal to my own particular tastes, I’m presently wrestling an illness that dulls my wits—not to mention that effusiveness often makes me uncomfortable, anyway. But The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps is really damn good. It’s a literary style of sword-and-sorcery, a genre that, in my experience, is very difficult to find, and very difficult to do well. Samuel R. Delany did, in the Nevèrÿon books and stories, and there’s a something of the taste of Nevèrÿon about The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps, not least the relationship between two men (demigods?) and the sheer delight it takes in its prose, and in the sharp, edged precision of its fantastical weirdness.

If I were to describe The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps in terms of its apparent plot, it would seem a cliché. Man and beloved travel, encounter problems, find—and fight—monstrous creature in a magical wilderness. But this is an altogether deeper and more layered work than that sketch implies.

Since leaving his homeland, Demane has been known as the Sorcerer. He’s descended from gods, it seems; as is the captain of the caravan which Demane joins in its trek across a desert wasteland and through the Wildeeps to reach Great Olorum. Demane is in love with Captain Isa, a love that is a consuming passion. But it’s also sharp-edged and filled with misunderstandings: Just because Demane loves Isa—and his feelings are at least in some degree reciprocated—doesn’t mean he understands the other man; doesn’t mean their relationship isn’t full of difficulties.

It’s odd for me to read a story—a sword-and-sorcery story—where most of the characters speak in the register of African-American English, but it rapidly feels natural: a lot more natural, in fact, than the occasional archaising tendencies that sometimes sword and sorcery falls prey to. This use of language—a disruptive use, for the genre—carries over into The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps‘ interest in the problems of translation, of navigating the worlds of language and how operating in a second or third language imposes barriers. Demane can converse in his own language about the nature of the gods in magico-scientific terms:

“Exigencies of FTL,” Demane answered. Distracted by a glimpse from the corners of his eye, he lapsed into a liturgical dialect. “Superluminal travel is noncorporeal: a body must become light.” A tall thin man passed by: some stranger, not the captain. “The gods could only carry Homo celestialis with them, you see, because the angels had already learned to make their bodies light. But most sapiens—even those of us with fully expressed theogenetica—haven’t yet attained the psionic phylogeny necessary to sublimnify the organism.”

But when he goes to talk to the caravan master, in another language, he struggles to express himself (a struggle anyone who’s had to even briefly get along for work in a second language in which they’re not sure of their ground will find familiar):

“Master Suresh, the Road, she,” (he? it? shoot! which one?) “is right there. I see she.” (No, her, shouldn’t it be? Yes, it should.)

It’s an interesting vein running through the novella, an interesting undertone of linguistic tension alongside the violence and tension of the life of the caravan guards, the tension of Demane’s relationship with Isa. Interesting, too, is the use of footnotes to leap forwards—or sometimes sideways—in the narrative. The footnotes have an air of regret, of melancholy, that colours the text: I’m inclined to read The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps as tragedy.

I don’t know that I really liked The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps. I’m not fond of tragedy—and I do prefer my stories to have at least a token female presence. But I admire it. It’s skilfully written, and left me thoughtful at its end. I can recommend it as technically excellent, even if my emotional response is entirely ambivalent.

The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps is available September 1 from Tor.com Publishing.

Read excerpts from the novella here on Tor.com.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.