All martyrdoms are difficult…

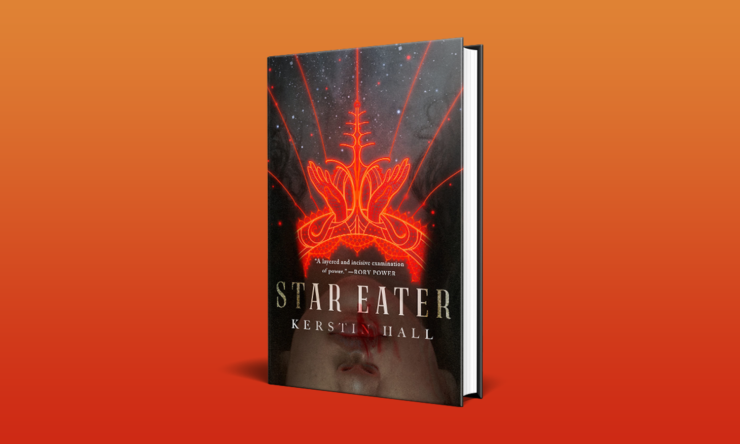

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Kerstin Hall’s dark fantasy, Star Eater—arriving June 22nd from Tordotcom Publishing.

Elfreda Raughn will avoid pregnancy if it kills her, and one way or another, it will kill her. Though she’s able to stomach her gruesome day-to-day duties, the reality of preserving the Sisterhood of Aytrium’s magical bloodline horrifies her. She wants out, whatever the cost.

So when a shadowy faction approaches Elfreda with an offer of escape, she leaps at the opportunity. As their spy, she gains access to the highest reaches of the Sisterhood, and enters a glittering world of opulent parties, subtle deceptions, and unexpected bloodshed.

A phantasmagorical indictment of hereditary power, Star Eater takes readers deep into a perilous and uncanny world where even the most powerful women are forced to choose what sacrifices they will make, so that they might have any choice at all.

Chapter One

The sun skimmed over yellowing leaves and filtered through the branches. Birds darted amongst the trees, passing from shafts of light into shadow, their feathers catching silver. Too hot, too close, the woods themselves seemed restless. Under our feet, the leaf litter crunched, and our white robes rustled as we wound along the path.

I was focussed on my breathing. In and out, in and out. Nice and slow and easy. Keep my mind on the immediate and tangible: the warm air brushing the nape of my neck, the loose, brittle earth under my shoes. Cicadas hissed, and I set my teeth. It had been seven days since I had last seen Finn, and I could feel the pressure building behind my eyes.

Concentrate, I told myself. Leave no room for panic.

In some respects, I had been lucky. The Moon Pillar pilgrimage was the shortest; only a day’s journey from the city. Unfortunately, this trip had taken far longer than usual. Herald Vay Lusor had directed the cohort to stop at every settlement along the route; we were to bless the citizens, listen to their grievances, and collect any petitions or entreaties. Excessive? Probably. But with the drought dragging on, the Council had deemed our support for the farmers a top priority. If they turned on us, the city would starve.

That was all very well. I just had far more pressing personal concerns.

Before every Pillar pilgrimage, every errand that took me beyond the Fields, I arranged to see Finn. While the journey to the Mud Pillar had cut it fine—six days there and back—the others had proved manageable. Not this time. Work had overwhelmed me, and then an Acolyte broke her wrist during a Renewal. I was suddenly called to serve as her substitute.

So here I was. Day seven, and in deep shit.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

The trees thinned and the path grew wider, the dry undergrowth giving way to short, softer grass. We had arrived.

The Moon Pillar stood in the middle of the clearing, the massive granite column split down the centre by the roots of a long-dead beech tree. White and leafless, the branches threw jagged lines of shadow over the stone, and in the shade gleamed thousands of names. Every Sister throughout the history of Aytrium was memorialised here. When we died, the Order carved our names into the Pillars and filled in the letters with gold.

The cohort fanned out to ring the monument. I knelt and laid my forehead against the dark earth. Dirt anointed my face, blades of grass brushed my cheeks. I rested the pads of my thumbs against the base of my skull, pressing my other fingertips together to gesture submission.

Calm down. Just get through it.

Deep within my chest, my mother’s power quickened. I stilled, letting the rhythm of my blood drown my other senses. The woods grew silent. Faintly, I could hear the slow breathing of my Sisters. Beneath that, quieter still, the sleepy heartbeat of Aytrium itself. Not a true pulse—it was only the echo of our ancestors’ power. I drew out the store of lace nestled within my core, and coaxed the warm thread to twine with the Pillar’s glacial current. Within seconds, my skin grew cold as the monument pulled lace from my veins.

On my first pilgrimage, I’d instinctively recoiled and severed the connection. The older members of my cohort had laughed at me.

The air around the Moon Pillar hummed as power drained into the ground. Deep vibrations rattled my teeth. Once my lace was spent, I sat back on my heels.

A six-legged goat stood tethered to the tree.

The animal had not been there when I started the rite. It bleated and tugged at the rope, straining to free itself. Its eye sockets were empty and lidless.

I did not allow myself to react. The goat tossed its head. Its fur was ink-black, except for the two white stripes running from its nose to its horns. Its nostrils flared.

Other members of the cohort began to sit up, their lace spent. Some gazed absently at the Pillar, while others watched the Sisters still occupied with the rite.

The goat struggled. Its legs moved awkwardly; a stray hoof drew blood from a rear shin. I sensed it too, the prickling dread. Beneath my knees, the earth trembled.

The last of the Sisters completed the rite. I stood, brushing dirt off my robes. I did not rush or speak. My face remained impassive. As usual, I allowed the others to lead the way, dropping to the rear of the cohort. The goat, now frenzied, scrabbled in the grass as the heavy footfalls grew ever louder, but I betrayed nothing, not a flicker of fear. I kept my gaze fixed on the ground and followed the Sisters ahead of me. I did not look back.

The goat screamed once in terror. Its hooves scrabbled against the earth and there was a sickening crunch, like bones crushed beneath the wheels of a cart.

The women ahead of me whispered to one another. Herald Lusor, at the head of the column, recited a ritual devotion to the Eater. Her voice rang sweet and clear.

“For your nourishment, for our nourishment, for the absolution of our mistakes, we give thanks. For your grace, for your sacrifice, for your wisdom, we give thanks. Let us lay our bodies beside yours, let us serve as we may.”

Step by step, the pressure inside my skull eased. I relaxed my jaw. I was clear; we had moved outside of the vision’s range. Not that I could see how I would ever make it back to the city like this.

Sunlight scattered through the branches overhead, warming my face. The low conversation of the Sisters blended with birdsong and the rhythm of our footfalls.

“Have you heard from Ilva recently?”

“Wasn’t she dating…”

“—she said nothing… I think so.”

Breathe. Keep walking.

A year ago, almost to the day, I had awoken to find my dormitory room coated in a layer of ash. When I touched it, the powder had melted like frost. My first vision, just as I’d been formally inducted as an Acolyte.

The cohort reached the waypoint. A web of red scarves hung from the tree’s branches. Beaded tassels and tiny copper chimes clinked in the breeze, and a rusted bell hung in the highest reaches of the canopy. Herald Lusor placed her palms flat on the smooth bark of the trunk. A pause, then the bell rang out, and a startled flock of sparrows took to the air.

As far as I was aware, anyone could enter the woods without announcing themselves, but the Pillar Houses’ zero tolerance policy for trespassers was notorious. Once, on the way to the Salt Pillar, I had seen the bodies of intruders hanged along the roadside. Their bare chests were branded with the two overlapping triangles that marked them as heretics.

Over the trees, our signal was answered by a second bell from the Moon House.

Herald Lusor removed her hands from the trunk and turned to face us.

“Thank you for your efforts, everyone,” she said. “After the delays this morning, I’ve decided that we should spend the night in Halowith. Are there any objections?”

My stomach sank. The other Sisters murmured approval, and I could say nothing, not without drawing attention to myself.

“Then it’s decided,” said Lusor. “Let’s move.”

The woods gave way to farmland; we crossed a stone bridge over a dry riverbed and emerged at the border of the orchards. Beyond the low timber fence, plum trees ran in parallel lines all the way to Fort Sirus. Workers tended to them with buckets, and a few waved to us. In the heat, their faces rippled like the surface of water. Pale pink blossoms lingered on the lower branches of the trees, dark fruit ripened higher up, and the barest whiff of fermentation carried on the breeze.

I could run, I thought, trudging down the road. My legs were leaden. I could vanish during the night, make up some excuse once I reach the city. A plausible emergency.

I almost collided with the Herald in front of me when she slowed. I looked up. The other members of the cohort were muttering to one another. Herald Lusor raised her hand.

The path ahead was deserted. The orchards were quiet. For a moment, I could detect nothing out of the ordinary.

Then I saw the man.

He crouched in the riverbed running alongside the road, facing away from us. It would have been easy to overlook him. Dust powdered his skin, hair, and clothes a uniform brown.

“Sir?” said Lusor.

Even as we approached, he remained stock-still, his arms wrapped over his head, neck curled toward his chest.

“Are you all right, sir?”

No response.

“Vay…” warned Herald Drishne, the cohort’s second-in-command.

Thick drops of blood rolled down the man’s arms where his skin had split open. I could see the lines of shallow red gouges through the ripped sleeves of his overalls. He had been scratching himself.

Lusor gestured, and we spread outwards to flank him.

“Please stand up,” she said, without inflection. “I need you to identify yourself.”

The man twitched. The motion undulated across the whole length of his spine. Then he was motionless again. His chest did not rise or fall; he could have been carved from the wood of the plum trees. Now that we stood closer to him, I could hear a furtive rasping sound, something between breathing and growling.

Lusor nodded curtly to us. I slipped my hand into the pocket of my robes and found my emergency vial. I removed the stopper with my teeth and swallowed the sacrament inside. It slithered down my throat, cold and salty.

The rasping ceased.

Lusor made a swift slicing motion with her hand. We obeyed. Thirteen nets of lace flew through the air, snapping around the man’s shoulders and pinning him to the spot.

He did not make a sound.

Sweat gleamed on Lusor’s forehead. “Hold him.”

We watched in absolute silence as she stepped into the gully and circled around the man.

“Sebet. Raughn.”

I started.

“Drop your nets and come here.”

Fine plumes of ochre dust rose around my feet. No one else spoke. Acolyte Fian Sebet and I were the youngest members of the cohort, and the least skilled in lacework.

Lusor never took her eyes off our prisoner. She lowered her voice so that only we could hear her. “Raughn, I saw your placement test scores. Your memory’s good, right?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I want you to make a report to the Moon House. Repeat exactly what I tell you to Reverend Shaelean Cyde, and request immediate assistance. Understood?”

“Understood.”

She recited her report to me. When she finished, I nodded.

“Do you need to hear that again?” she asked.

“No, Herald.”

“Good. Sebet, I want you to run to Halowith’s chapter house and summon the Sisters on duty. They must help us to contain the Haunt until the retrieval cohort arrives.”

“Understood,” said Sebet.

The frozen man stared at me. His expression was unfathomable, his mouth worked soundlessly. Between the ceaseless movement of his lips, I could see two sets of teeth, the back row needle-sharp and pointed. Bubbles of bloody saliva drooled from his chin.

“Raughn?”

I snapped out of my daze. “Sorry.”

“Try to stay focussed, okay?” said Lusor, not unkindly.

“Yes, Herald.”

“Once reserves arrive from Halowith, I’ll send a second runner after you.”

I gestured compliance, weaving the tips of my fingers together and drawing them downwards.

Lusor dismissed me. “Go.”

I clambered out of the gulley, and the cohort parted to let me through. Even as I hurried away from him, I could still see the Haunt’s lips moving in my mind.

“Closer, closer, closer…” he repeated.

The sun had passed its meridian, but the heat blazed on, and it was scarcely any cooler beneath the beech trees. Perspiration trickled along the ridges of my spine. The Moon House was on the south side of the Pillar. Unless I circumvented the entire wood, the only route was back toward the vision. And I knew it was still there. The pressure in my skull was mounting again.

At the waypoint, I shut my eyes and drew on my lace, curling a thin thread of power through the tree’s protective web. I found the hidden cord and pulled. Overhead, the bell clanged.

When I opened my eyes, a rose lay to the right of the path. Red, careless, a flower dropped from a lover’s bouquet. The outer petals were marred by bruise-coloured marks.

I shook my head and took the left path, away from the Pillar.

The Moon House answered, their bell ringing in the distance. They must have been confused, but with luck they would ride out to meet me.

I came across a second rose, and then a third, tucked into the crook of old tree roots. A fourth, dangling from the branches. Their petals fluttered in the wind. Everywhere I looked, more appeared. Bruised, incongruous, a line of red dripped to the base of a fallen tree, where the petals pooled beneath the trunk. A slender black foreleg lay half submerged in the flowers. The rest of the goat was nowhere to be seen.

“Eater preserve me,” I muttered.

The trees thickened, obscuring the sky, and the sound of my footfalls soaked into the dense vegetation. I had never been this deep in the woods before. Strange noises rose and fell, furtive creaks and chirrups, the sharp buzzing of unseen insects, the whirr of wings.

A blackwing hen burst from the undergrowth ahead of me. I jumped and swore. It flapped up into the canopy, squawking.

“Sorry,” I said.

I came to a bend in the path and then, quite abruptly, the Moon House was spread out before me.

The complex rested against the rise of a steep hill, a semicircle of twelve dark brick buildings nestled in the shadows of the trees. A group of Sisters had assembled in the yard in front of the House stables. Oblates rushed to saddle Cats, and Reverend Cyde directed the preparations.

She saw me approach. A flicker of surprise crossed her face.

“Elfreda? What’s going on?”

I reached the yard.

“Acolyte Elfreda Raughn, delivering a report from Pilgrim Guide Vay Lusor of cohort eight, identification code 2649B.”

“Proceed,” said Reverend Cyde.

I spoke loudly enough for everyone to hear. “Stage Three Haunt apprehended on the West Orchard Road, just past the bridge. Individual is largely unresponsive and contained by eleven Sisters. Reinforcement urgently required.”

Reverend Cyde nodded and turned to address her subordinates. “Hina, Samas, ride ahead and provide support. Everyone else, prepare the retrieval cart.”

My part done, I moved to leave. This was my chance. If I disappeared now, I could make it back to the city by nightfall. In the chaos, the Sisterhood would overlook the irregularity and—

“Elfreda,” said Reverend Cyde.

“Yes, Reverend?”

“Wait in my office please.”

My hopes crumbled.

“Yes, Reverend,” I said.

Chapter Two

Reverend Cyde’s assistant offered me tea.

The office was spacious and airy, with large windows overlooking the stables. Bookshelves dominated the right- hand side of the room. The vellum-bound volumes were arranged alphabetically and with meticulous care, more valuable books locked behind glass panels. Before taking her position at the Moon House, Shaelean Cyde had served as the Chief Archivist at the Department of Memories.

I sat in a plush blue armchair by the window and watched the tree line. The pressure in my head was faint now. The woods were still.

I took a sip of my tea. It tasted bitter.

The office was on the second floor of the main dormitory building. A longcase clock ticked in the passage outside, and old floorboards creaked from time to time. Through the window, I could see three Oblates locked in serious conversation. Most of the Moon House residents were accompanying the Haunt to the Edge, leaving the compound in the care of a skeleton guard.

Swift footsteps beyond the door, and then Reverend Cyde strode into the room. I half rose from my seat, but she signalled for me to dispense with formalities.

“You’ll be pleased to hear that the situation has been contained,” she said, taking a seat behind her desk. “No one was hurt.”

Cyde was old for a Reverend, nearing sixty, with unlined brown skin and a no-nonsense haircut. On her shoulder, she wore a midnight blue badge and crescent moon pin to designate her rank. Head Custodian of the Moon House, one of the most powerful people outside of Ceyrun.

“I will need to file a report.” She opened her drawer and drew out a clean sheet of paper. Her movements were brisk, effortlessly efficient. “I would like to hear your version of events.”

I nodded. “Yes, Reverend.”

“But first”—she folded her hands on the desk in front of her, fixing me with her stare—“are you all right?”

“Yes, Reverend.”

“Please stop saying that.”

“Ye—okay.”

She gave me a hard look. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” I lied with greater conviction. “I’m fine. Thank you for your concern.”

Cyde had been something like a mentor to my mother, back when the Reverend still lived in the city. I was surprised that she had recognised me in the yard; the last time we met, I had been fifteen. So much had changed since then that this reunion made me feel awkward.

“I’m glad to hear that.” She wet the nib of her pen in her inkwell. “Right. This is mostly to corroborate what I already know, but can you describe the events leading up to your cohort’s discovery of the Haunt?”

I nodded. “We completed the Pillar maintenance, and rang the bell at the waypoint. Pilgrim Guide Lusor proposed spending the night in Halowith.”

“Why?”

“The pilgrimage took longer than anticipated. We would only have reached Ceyrun after dark.”

She made a note. “The cohort was in agreement?”

With one notable exception. “Yes, we were tired. We left the woods via the north-east bridge, and encountered the Haunt shortly after that.”

“Did any civilians see you?”

“A few farmers saw us on the road, but I don’t think they witnessed our capture of the Haunt. At least, that was the situation when Herald Lusor sent me here.”

“How did Herald Lusor react to the Haunt?”

I frowned. “She was calm, under the circumstances.”

“Did anyone in the cohort behave unexpectedly?”

“Not that I recall. We were surprised.”

“I would imagine so.” She did not look up from the page, still writing. “So there was no one whose reaction to the Haunt struck you as out of the ordinary?”

“No, Reverend.”

She finished her sentence and set down her pen. “That should do, unless there’s anything else you want to add?”

I thought for a moment, gazing down at the floor. I gathered my nerve.

“Reverend, do you need someone to deliver that report?”

“Hm?”

“I would be happy to courier it to Ceyrun.”

“How generous of you.” Cyde leaned back in her chair, folding her hands in her lap. Her dark eyes gleamed. “Elfreda, it strikes me that you are very eager to return to the city.”

“Uh…”

“Any particular reason?”

“The Council should be made aware of the situation as soon as possible.”

Cyde raised an eyebrow fractionally. She was far too sharp for my liking, but then, she had been a Councilwoman prior to her retirement.

“That’s it?” she asked.

I decided that a measure of truth might help my case. “It’s my mother’s anniversary tomorrow. I had hoped to be there.”

Her face clouded.

“Oh. Of course,” she said.

“I realise it might seem sentimental, but—”

“No.” She shook her head. “No, I understand. It’s been a year already, hasn’t it?”

I nodded.

Cyde stood up. She walked over to the window, eyes sweeping the woods, hands clasped behind her back.

“You won’t be able to cover the distance on foot,” she said. “Not before sunset. You would need a Cat.”

She caught my expression and her lips curved upwards in amusement.

“I have a precondition,” she said.

“Yes, Rev… Yes?”

“Make that two conditions. Firstly, ‘Shaelean’ is fine; I’ve known you since you were six. Secondly, I want you to consider applying for reassignment.”

“Reassignment?”

“To the Moon House.”

I blinked.

“I don’t need an answer now,” she said, “but I want you to think about it.”

Positions at the Pillar Houses were highly sought after; House staff were exempt from Renewal duty for months at a time, received a much higher stipend, and enjoyed better lodging. Most Acolytes would not dream of applying in their first five years. The fact that Cyde had implicitly offered a post to me bordered on the scandalous.

“Thank you,” I said, disoriented. “I… I will consider it.”

“You would like working here. Consider it my favour to your mother.” She released her hands from behind her back. “I’ll finish up my report; you may head down to the stables in the meantime.”

I gestured respect and stood. She returned to her desk.

The lacquered walls of the passage outside the Reverend’s office flickered with the shadows of incipient visions; brief impressions of dark shapes that twitched and rolled like flames in the wind. I shut the door behind me and pressed the palms of my hands to my eyes. My head pounded; colours bloomed under my eyelids.

“Shit,” I muttered.

I walked unsteadily toward the stairs. The floor was covered in soft woven rugs, the walls lined with old portraits of prior Custodians. Their painted faces bulged; their bodies melted and reformed within their gilt frames. The oil paint glistened as if newly wet. Behind me, the clock struck fifteen, and its gong reverberated through the walls of the Moon House. I felt the sound within my bones.

It was better outside. The sun touched the highest branches of the trees and stained the buildings orange. I passed the locked entrance to the House’s underground Martyrium, dry grass crunching under my boots. The air remained blistering, oven-hot and thick. With luck, the humidity heralded a storm.

A Cat handler reclined in the shade of the stables. Sweat shone on her forehead and beaded her upper lip.

“I am to courier a report for Reverend Cyde,” I said.

She straightened, eyes narrowed. “Now?”

“She’ll be down in a minute.”

The handler, who I guessed was an Oblate despite her plain clothes, got up and dusted off the back of her trousers. I understood her suspicion. The use of the Cats was generally restricted to Heralds and Reverends, or Acolytes who worked in communication. I clearly did not fit into any of those categories.

“You’ve ridden one before?” she asked.

I shook my head.

“I’ll saddle Claws, then. He’s the easiest to control.”

The stable was largely empty; most of the Cats were with the retrieval cohort. Three animals remained; the handler approached the smallest.

Haqules, to use their proper name, were intimidating. They were as lithe as their smaller feline cousins, with eyes that saw as well in the dark as in daylight and excellent hearing. Adults stood shoulder height to humans, and a fully grown Cat’s head was as large as my entire torso. Their fur was coarse and variegated, their canines capable of puncturing iron. Although few other animals could slow a Haunt, prides of Cats tore them to pieces.

When interacting with their human handlers, however, they had the personality of puppies.

“Heel, Claws,” called the handler.

The Moon House housed eight Cats, seven for service and one reserved for Reverend Cyde’s personal use. Claws was evidently the runt of the litter. He bounded over to the handler, forked tail swaying.

“Good boy!” She stood on tiptoe and scratched behind his massive, bat-like ears. He shivered with pleasure. The handler cast me another doubtful look.

“He’s very quick,” she said.

“I’ll manage.”

I kept out of the way while the handler fit a leather harness to Claws’s back. One of the other Cats wandered over to investigate, sniffing my clothes. I patted her, a little uncertain. She sneezed, arched her back, and ambled off into the cooler shadows of the stable.

Reverend Cyde’s boots crunched on the grass outside and she appeared in the entrance. She handed a wax-sealed letter to me.

“Deliver this to the Council as soon as you reach Ceyrun,” she said.

“Yes, Reverend.”

She smiled. “I despair.”

“Kneel, boy,” said the handler.

Claws crouched. I slung my leg over his side. His fur smelled of grass and prickled against my exposed skin. I hugged him around the neck, feeling his muscles shift beneath me.

“You can just sit tight. He’ll head to the city on his own.” The handler adjusted the leg straps of Claws’s harness until they squeezed my calves. “You want to stop, tell him. He’s smart.”

She tapped his rump, and he rose. I swayed dangerously as his body tilted.

“Have a safe trip,” said Cyde.

The handler unclipped the Cat’s restraint from the collar around his neck.

“City, Claws,” she ordered.

The sensation was like falling. Half a ton of muscle and fur surged through the stable door and out into the yard.

If not for the harness, I would have lost my balance within the first thirty seconds. I clung to the Cat’s neck, helpless as a ragdoll, as we streaked into the woods. Each bound hurtled us over rocks and shrubs and fallen trees; wind whipped my face and roared in my ears. Claws strayed from the path, finding his own route, but he moved with absolute surety, silent and precise and lightning-quick.

I didn’t care about the discomfort; I was finally heading in the right direction. The pressure clouding my mind evaporated and I laughed with delight.

We slowed once we reached Orchard Road. The workers had left the farms, and we loped along the path alone. Claws panted and I shifted in the harness, trying to find a more natural seat. The road ended at a T-junction; one way leading to Halowith, the other toward the main road and the city. Without any instruction from me, Claws turned left and started up the steep hill.

I squinted at the sky. There was at least an hour left until nightfall. If we continued at our current pace, we would reach the gates in time.

We crested the slope, and the capital province of Aytrium spread out before us. The basin of Malas Lake stretched from the base of the hill into the far distance. The water levels had withered over the last two hot seasons, and the banks were wide and bone-pale. Iron pipes snaked from the centre of the lake to the small villages dotting the northern shoreline. The great waterwheels stood still and dry.

Beyond lay the Fields, yellow with millet and corn, and then the city. Ceyrun’s pale gold walls rose a hundred feet from the valley floor, shielding the lower quarters of the city from view. From this distance, I could see the oldest trees of the Central Gardens, the taller houses of the Minor Quadrants, and Martyrium Hill. Glass and polished stone reflected the sunset, and shadows thickened at the base of the eastern wall.

Claws skidded down the flinty road, struggling for purchase. I lurched forward, and only the harness prevented me from flying over the top of his head. He mewed when I pulled his fur too hard.

“Sorry,” I said, and patted the side of his neck. His ears flicked.

The road ran alongside the edge of the lake. I wiped sweat off my face. It was a few degrees cooler here, and the faint breeze carried the smell of mud. Jewelled dragonflies flitted through the air. Amberwings. They were breeding in larger numbers this year.

The path ahead bubbled.

Claws slowed, and his hackles rose.

“It’s okay,” I whispered.

He growled. I didn’t think that he could sense the vision, but he knew that I was disturbed.

“Keep going,” I told him. “Go on.”

He took a few uncertain steps forward. I continued to murmur encouragingly. The ground beneath his paws reddened, dark blood seeping out of the dirt. The smell of smoke and jasmine caught in my throat, chokingly sweet.

“They are coming, they are coming, they are coming, they are coming, they are coming…” The voice swelled from the earth below us: female, rasping, a relentless stream of fear. As I watched, the ground bulged with strange protrusions, fat red seedlings sprouting and unfurling in the sunlight. They squirmed beneath Claws’s paws and burst like pustules. I flinched and pulled my feet up higher. “They are coming, they are coming.”

The protrusions grew taller. They wound around Claws’s legs like river weeds.

“They are here.”

A scream filled the air, and I clasped my hands to my ears. The sound was inhuman and agonised; it stretched on and on, so loud that I thought my eardrums would rupture. The protrusions reached my ankles, and their touch seared my skin. I kicked them away.

With a wet, tearing noise like meat pulled apart, the vision ended. The protrusions crumpled to dust.

I breathed hard. Claws shied sideways, shaking his head and whining. His claws extended and scratched lines in the dirt.

“It’s all right,” I said. “Hey. It’s all right, boy. I didn’t mean to scare you.”

I tried to stroke his head, but he snapped at me. I withdrew my fingers. The fur along the ridge of his spine stood straight up.

“Why don’t you let me down, okay?” I said gently. “It’s not far now.”

He whined again, but bent his knees. I loosened the harness straps, and slid off him.

“That’s better, isn’t it?”

I steadied myself against his flank, and Claws shivered. My ankle stung where the vision had touched me. Not serious. I stroked the Cat in jerky, mechanical motions. Had to keep my composure.

Millet grew on both sides of the road; we had almost reached the city walls. Up ahead, I could hear workers singing the day-end song. The evening was humid. Crickets rasped from the grain, and flies buzzed circles around us.

I took another deep breath. When I started walking, Claws followed me.

The singing grew louder as we approached the silos. Although harvest time was still a month away, the Fields bustled with temporary labourers. The Department of Food Management was collaborating with Water and Sanitation to introduce a new irrigation system, drilling boreholes below the Fields. It was proving more complex—and expensive—than anticipated. At around ten feet deep, the drills in the northern-most Fields had hit a hard bed of granite. The excavation team had assured us that they would break through the rock, but not before the end of the week.

I attracted a few curious looks and deferential gestures as I approached the city. I must have appeared important, with a Cat walking behind me. I returned the greetings.

Sing the storm clouds, sing them in,

There will be food on our tables,

There will be food in our stores,

The Eater’s grace upon us.

The day-end song was familiar and mindless. My mother had told me that the lyrics were altered seventy years ago. I’m not sure how she knew of the original, but she liked to collect odd information like that. In my head, I recited the older version.

Call your children, call them in,

There will be blood in the fields,

There will be blood on our hands,

It will not be ours.

I circled around the side of the silo and leaned against the wall. Claws yawned and stretched. He lay down, flapping his ears to fan himself. The workers were returning their tools to the equipment store; they talked loudly and occasionally laughed. I scanned their faces.

“Hey.”

I turned.

All the visions threatening to emerge from the shadows of the silos bled away. The tension inside my chest eased.

“Good evening, Finn.”

“‘Good evening,’ El. Feeling formal today?”

Finn was tall and wiry, with messy shoulder-length hair and a wide smile. He carried himself with a disarming confidence, propping a dusty pitchfork across his shoulders as he walked over to me.

“Sorry.” I shook my head. “I’m all over the place.”

“Don’t apologize. What’s with the Cat?”

Claws eyed Finn suspiciously and yawned again, cracking his jaw. His long teeth gleamed.

“That would be Claws. Reverend Cyde of the Moon House had a report for the Council.” I lifted my bag. “I volunteered to deliver it.”

Finn checked if anyone was close enough to overhear us, and lowered his voice.

“Are you okay?” he asked.

“Now? Yes.”

“Good, because I was worried out of my mind.” He glanced toward the queue of workers clocking in with the shift supervisor. “Can I walk you to the Council Building?”

“Sure, if you want to.”

“I do.” He smiled. “Let me just sign off on this shift.”

With my visions banished, I allowed myself to relax a little. Finn had been my best friend since I was seven, and was one of the few people I trusted completely. In his company, I felt stable, secure in myself, which seemed key to suppressing the visions. I watched as he joined the queue of workers, cracking a joke that caused the people around him to groan. These days, he was doing well. I was glad to see him happy, even if it left me feeling a little lonely.

The breeze shivered across the pale gold fields, brushing the shadows of the city wall. I rubbed my arms. Hopefully, delivering the report would not take too long.

Finn returned, stretching his arms overhead.

“I’ve discovered that I am not cut out for farming,” he said with a grimace. “Or hard labour, generally.”

“You look tired.”

“Thank you for noticing. I feel ready to drop dead.”

“So dramatic.”

Finn made a show of pretending to faint, leaning against the silo wall for support. Claws growled.

“Don’t upset my Cat,” I said, although I could not help smiling. “Can you drag yourself to the city please?”

“So… far…”

“Enjoy sleeping in the Fields, then.”

“That sounds pretty appealing right about now.” He straightened. “But I’ve got a shift at the Candle tonight, so unfortunately it’s not an option.”

“Oh. You don’t need to walk halfway across the city if…”

He waved off my suggestion. “I want to. Don’t worry, I’m just whining. Let’s go.”

Claws rose reluctantly. Ahead of us, the city walls stretched tall and shining, and we followed the path that led to Ceyrun.

Chapter Three

The Council Building was situated in the Minor East Quadrant, the wealthiest sector of the city. It stood four storeys high, overlooking the college grounds and the Department of Memories. The old building projected an air of stately grandeur, with its yellow stone walls and fine latticework, its mythic friezes, its jutting balconies and sloping gullwing roof. The oldest wing of the building was home to the Conclave of Representatives, and dated back to the Great Fire of the Ash Disciple rebellion almost four hundred years ago.

I seldom had reason to visit the Council Building. In fact, I had not seen the interior since my induction as an Acolyte last year.

“I’m not sure how long I’ll be.” I gazed up at the carved pillars. Sisters were leaving the building, work concluded for the day. “If the Council is in session, it could be a while.”

“I’ll take that as a hint,” said Finn. “Want to drop by the Candle afterwards?”

“It’s been a long day.”

“I thought you might say that.” A strange expression passed over his face. “El, I’ve been thinking…”

He trailed off.

“What is it?”

“Probably nothing. Forget it.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah.” He smiled. “Yeah, I’m sure. Listen, are you free tomorrow? Millie has plans.”

“What kind of plans?”

“It’s Daje’s birthday. I’m supposed to convince you to attend. So, you know, please come.”

I laughed. “Convincing.”

“I try. So?”

“I don’t know, would Daje really want me there? We aren’t exactly close.”

Finn shook his head. “It’s fine, it’s just a casual thing in the Gardens. I get the impression it’s more for Millie’s benefit anyway.”

“Still…”

“He won’t mind.”

I thought for a moment. Sisters were granted a day off after any pilgrimage, and although I wanted to see my mother, that wouldn’t take more than an hour.

“All right,” I said, still a little uncertain. “If you’re sure it’s okay.”

Finn grinned. “Great. Meet me at the graveyard at third bell?”

“Fourth?”

“Sure.” He leaned forward quickly and kissed me on the cheek. “See you then.”

He was walking away from me before I could think of anything to say. My cheek burned, and I felt, suddenly, as if the eyes of the whole city were upon me.

I hurried up the steps. Reckless idiot.

Cool, dry air wafted out into the evening; the walls of the building were thick, and chambers within always cold. At the entrance, the Acolyte on guard gestured welcome to me.

“Is the Council still in session?” I asked.

She nodded. “I believe so, but they should finish shortly. Do you need help finding them?”

“I think I’ll manage, but thank you.”

My footfalls echoed on the tiles. The foyer was vast and dim; red carpeted stairs bordered the chamber, and a great brass chandelier hung from the ceiling. Marble busts of prior Councilwomen sat in recessed alcoves. Their eyes seemed faintly accusatory to me. A statue of the Star Eater stood on a raised pedestal in the centre of the room. The old woman had a stern expression, but her hands reached outwards, ready to embrace penitents. Small offerings covered her bare feet.

I paused to pay respect, then headed up the right-hand staircase to the third floor. The workday was done, so the Council must be running late. Probably struggling to reach consensus on the water crisis.

Oil paintings crowded the walls of the eastern wing corridors. The old floorboards groaned as I made my way toward the Council chambers. I had never been to this part of the building before, and could not quite shake the sense that I was trespassing. The murky glass of the windows only let in thin, watery light, and the smell of lantern oil and varnish was cloying.

I followed the sound of voices. As I got closer, I could catch snatches of an argument.

“… won’t be anything left to preserve if they tear down the walls!”

Someone spoke with a mollifying tone. I did not catch their words.

“I don’t think you understand the severity of the situation.” That was Reverend Deselle Somme, Head of Food Management. She spoke slowly and clearly, and her deep voice carried well. “If we don’t implement measures now, we are setting ourselves up for full-scale civilian revolt.”

An Acolyte stood outside the doors to the Conclave. She wore a heavy yellow uniform, with tasselled shoulders and a tricorn hat. When she caught my eye, she grimaced. Outside the door, the Reverends’ every word was audible.

“It’s high time that the radicals were served a reminder of who rules this city. We can handle the situation.”

“Who is ‘we,’ Jiana?” A new voice, icy and authoritative. “Because I’m fairly certain you mean ‘Enforcement can handle the situation,’ and that means I will have to handle the situation.”

“They’ve been at it for an hour,” the Acolyte whispered to me. “If you have a message, I can pass it on for you. This could last all night.”

I winced. “Unfortunately, it’s urgent.”

The Acolyte nodded sympathetically. “In that case, rather you than me.”

At least I was back in the city. If I could handle the visions, then surely I could face the Council. I raised my hand and knocked on the varnished wooden door.

“Your convenience is not a priority.”

“This is not about convenience. You know what will upset the civilians? The cancellation of a festival they’ve been preparing for since last year.”

The uniformed Acolyte gave me an embarrassed smile.

“They probably won’t hear you,” she whispered. “You’ll have to intrude.”

Better to get it over with. I steeled myself, and pushed open the door.

The Conclave of Representatives chamber fell quiet. The room was much larger than I had anticipated, with the thirteen representatives seated in a ring behind individual stone podiums. A huge map of the island was painted on the floor, the names of towns and rivers etched in gold. Three of the Reverends were on their feet, their argument stalled by my appearance. The other ten remained seated beneath the coloured banners of their departments.

I stepped inside and gestured respect and regret. My throat felt bone-dry.

“What is the meaning of this?” Reverend Jiana Morwin of the Department of Public Health fixed me with a cold stare. Her skin was flushed with anger.

“Please forgive my intrusion,” I rasped. I cleared my throat. “I have an emergency missive from Reverend Shaelean Cyde of the Moon House.”

“Whatever it is, I hardly think it justifies disrupting session.”

I swallowed. Although I knew who all the Councilwomen were, I had only ever spoken to Reverend Somme, who was the head of my department. The thirteen most powerful individuals on Aytrium, and I had barged into the middle of their meeting.

“Come now, Jiana,” said Reverend Yelina Celane, the Chief Archivist of the Department of Memories. Her robes bore the green quill insignia of her department, and she appeared quite at ease. She smiled at me. “No need to be rude. Your name, Acolyte?”

“Elfreda Raughn, Honoured Councilwoman.” I drew Cyde’s report out of my bag and hesitated, unsure who I should present it to. To my relief, Reverend Somme held out her hand.

“Very good,” said Reverend Celane. “Thank you for your service, Acolyte Raughn. You may go now.”

“One moment.”

Reverend Saskia Asan was the youngest member of the Council and its most recent addition. She served as the Commander General of the Department of Enforcement, the Sisterhood’s military force. Rumour suggested that she was one of the most talented lace-weavers of the last century, and, despite her coarse demeanour, one of the smartest women in the Sisterhood.

“You aren’t a House member,” she said. “Unless you’re wearing someone else’s robes.”

“I was part of the Moon Pillar pilgrimage and available to deliver Reverend Cyde’s report.”

“Please speak louder.”

“The House members were occupied,” I said, raising my voice. Other members of the Council whispered to one another. Sweat rolled down my back.

“Huh.” Reverend Asan folded her arms and slouched on her chair. “Irregular.”

Reverend Somme finished reading Cyde’s letter. Her gaze flicked toward Reverend Asan, and she set down the paper.

“Thank you, Elfreda, that will be all,” she said.

I bowed. The whispering grew louder. I backed out of the room and closed the heavy door behind me. My hands shook.

“What was all that about?” asked the Acolyte.

“I’m not authorised to say.” Although, given her position, she would no doubt find out shortly. One of the perks of her job, I imagined. I could hear the murmur of Reverend Somme’s voice as she read Cyde’s report to the Conclave, too low to understand. The Acolyte frowned at me.

“Enjoy your evening,” I said.

The truth would leak to the rest of the Order soon enough anyway. I doubted that the Reverends could keep the Haunt a secret, not after so many Sisters were involved in its capture and disposal. I hurried back down the corridor. The news would be all over the dormitories by tomorrow.

By the time I reached the entrance to the building, evening had fallen. An Oblate was lighting the votive candles at the base of the Star Eater’s statue, murmuring a devotional as she moved from one taper to the next. Tiny white moths fluttered around the open flames. The tiles below were already dotted with the singed wings of the dead.

Excerpted from Star Eater, copyright © 2021 by Kerstin Hall.