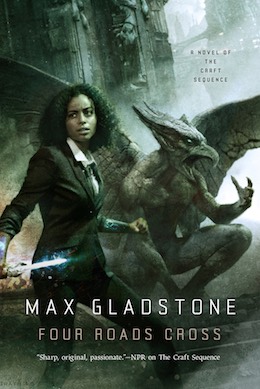

We’re excited to bring you four days of Four Roads Cross, the fifth book in Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence! Read chapters 4 and 5 below, or head back to the beginning with chapter 1!. Four Roads Cross publishes July 26th from Tor Books.

The great city of Alt Coulumb is in crisis. The moon goddess Seril, long thought dead, is back—and the people of Alt Coulumb aren’t happy. Protests rock the city, and Kos Everburning’s creditors attempt a hostile takeover of the fire god’s church. Tara Abernathy, the god’s in-house Craftswoman, must defend the church against the world’s fiercest necromantic firm—and against her old classmate, a rising star in the Craftwork world.

As if that weren’t enough, Cat and Raz, supporting characters from Three Parts Dead, are back too, fighting monster pirates; skeleton kings drink frozen cocktails, defying several principles of anatomy; jails, hospitals, and temples are broken into and out of; choirs of flame sing over Alt Coulumb; demons pose significant problems; a farmers’ market proves more important to world affairs than seems likely; doctors of theology strike back; Monk-Technician Abelard performs several miracles; The Rats! play Walsh’s Place; and dragons give almost-helpful counsel.

4

One does not need an expensive Hidden Schools degree to know the first step in crisis management: get ahead of the story. If that’s impossible, at least draw even with it. Tara, who had an expensive Hidden Schools degree, hunted Gavriel Jones.

The Crier’s Guild was more hive than office. Stringers, singers, and reporters buzzed like orange bees from desk to desk, alighting coffee mugs in hand to bother others working, or pollinate them with news.

“Late report by nightmare telegraph, lower trading on Shining Empire indices—”

“You hear the Suits busted Johnny Goodnight down by the docks, taking in a shipment?”

“No shit?”

“—Haven’t found a second source for this yet, but Walkers looks set to knock down those PQ slums for her new shopping center—”

“Still missing your bets for the ullamal bracket, Grindel’s about to close the door—”

“—Loan me a cigarette?”

“Do you really want it back?”

They didn’t let people back here, exactly, but Tara wasn’t people. She forced her papers into the receptionist’s face—I’m Ms. Abernathy, Craftswoman to the Church of Kos Everburning, we’re working on a case and want to check our facts, without pause for breath. Then she held the receptionist’s gaze for the ten seconds needed for the word “Craftswoman” to suggest shambling corpses and disemboweled gods. Not that most gods had bowels.

Useful mental image, anyway.

The young man grew paler and directed her to Jones: third desk from the back, on the left, one row in.

They’d thrown desks like these out of the Hidden Schools in Tara’s first year, chromed edges and fake wood tops that didn’t take the masquerade seriously, green metal frames, rattling drawers and sharp corners. Thrown them, she remembered, straight into the Crack in the World. If you have a hole in reality, why not chuck your garbage there? At the time they’d also thrown out a number of ratty office chairs like the one in which Gavriel Jones herself reclined, one muddy shoe propped on the desk. The Crier held a pencil in her mouth and a plainsong page inverted in her hand. She straightened the foot that propped her, then relaxed it again, rocking her chair back and forth. Her free hand beat syncopation on her thigh. A cigarette smoldered in the ashtray on her desk. Tara frowned at the ashtray and the smoke. She might work for Kos, but that didn’t mean she had to approve of the weird worship the fire god demanded.

Or maybe the Crier was just an addict.

“Ms. Jones.”

Jones’s hand paused. She stopped rocking and plucked the gnawed pencil from her teeth. “Ms. Abernathy. I took bets on when you would show up.”

“What was the spread?”

“You hit the sweet spot.”

“I’m getting predictable in my old age.”

“I won’t pull the story,” Jones said.

“Too predictable.”

“At least you’re not getting old. Not like the rest of us, anyway.” Jones pointed to the paper-strewn desktop. “Step into my office.”

Tara shifted a stack of blank staff paper and leaned against the desk. “You’re starting trouble.”

“We keep people informed. Safety’s the church’s job. And the Blacksuits’.”

“You didn’t see the Paupers’ Quarter market this morning when they sang your feature.”

“I can imagine, if it’s anything like the rubbernecking we had up north in the CBD.” She grinned. “Good tips today.”

“People are angry.”

“They have a right to be. Maybe you’re an operational atheist, but most folks don’t have the luxury. We’ve had problems with gargoyles before. If they’re back, if their Lady is, that’s news.” Jones had a way of looking up at Tara and seeming to look—not down, never down, but straight across, like a pin through Tara’s eyeball. “We deserve to know how, and why, the city’s changed beneath us.”

“Who are your sources?”

One of Jones’s lower front teeth had been broken off and capped with silver. “Do you really think I’d answer that question? If people are worshipping Seril, a church rep is the last person I’d tell.”

“I don’t need specifics,” Tara said.

“I met a girl in a bar who spun me a tale. She worked delivery, and some hoods jumped her and stole her satchel. Way the contract was written up, she was liable for everything inside. Small satchel, but you know Craftfolk. Whatever was in there, it was expensive— the debt would break her down to indentured zombiehood. She knew a story going around: if you’re in trouble, shed your blood, say a prayer. Someone will come help. Someone did.”

“What kind of bar was this?”

That silver-capped tooth flashed again.

“So you write this on the strength of a pair of pretty blue eyes—”

“Gray.” She slid her hands into her pockets. “Her eyes were gray. And that’s the last detail you get from me. But it got me asking around. Did you listen to the song?”

“I prefer to get my news straight from the source.”

“I did legwork, Ms. Abernathy. I have a folder of interviews you’ll never see unless a Blacksuit brings me something stiffer than a polite request. Women in the PQ started dreaming a year ago: a cave, the prayer, the blood. And before you scoff, I tried it myself. I got in trouble, bled, prayed. A gargoyle came.” Her voice lost all diffidence.

“You saw them.”

“Yes.”

“So you know they’re not a danger.”

“Can I get that on the record?”

Tara didn’t blink. “Based on your own research, all they’ve done is help people. They saved you, and in return you’ve thrown them into the spotlight, in front of people who fear and hate them.”

Jones stood—so they could look at each other face-to-face, Tara thought at first. But then the reporter turned round and leaned back against her desk by Tara’s side, arms crossed. They stared out together over the newsroom and its orange human-shaped bees. Typewriter keys rattled and carriage returns sang. Upstairs, a soprano practiced runs. “You don’t know me, Ms. Abernathy.”

“Not well, Ms. Jones.”

“I came up in the Times, in Dresediel Lex, before I moved east.”

Tara said nothing.

“The Skittersill Rising was my first big story. I saw the protest go wrong. I saw gods and Craftsmen strangle one another over a city as people died under them. I know better than to trust either side, much less both at once. Priests and wizards break people when it suits you. Hells, you break them by accident. A gargoyle saved me last night. They’re doing good work. But the city deserves the truth.”

“It’s not ready for this truth.”

“I’ve heard that before, and it stinks. Truth’s the only weapon folks like me—not Craftsmen or priests or Blacksuits, just payday drunks— have against folks like you. Trust me, it’s flimsy enough. You’ll be fine.”

“I’m on your side.”

“You think so. I don’t have the luxury of trust.” She turned to Tara. “Unless you’d care to tell me why a Craftswoman working for the Church of Kos would take such an interest in crushing reports of the gargoyles’ return?”

“If the gargoyles are back,” she said, choosing her words carefully, “they might raise new issues for the church. That makes them my responsibility.”

Jones looked down at the floor. “The dreams started about a year ago, after Kos died and rose again. There were gargoyles in the city when Kos died, too. Maybe they never left. It sounds like more than the gargoyles came back.”

Tara built walls of indifference around her panic. “That’s an . . . audacious theory.”

“And you began to work for the church at about the same time. You sorted out Kos’s resurrection, saved the city. Maybe when you brought him back, you brought something else, too. Or someone.”

Tara unclenched her hand. Murdering members of the press was generally frowned upon in polite society. “Do your editors know you make a habit of baseless accusations?”

“Don’t treat us like children, Ms. Abernathy—not you, not Lord Kos, not the priests or the gargoyles or the Goddess Herself. If the world’s changed, the people deserve to know.”

Time’s one jewel with many facets. Tara leaned against the desk. A year ago she stood in a graveyard beneath a starry sky, and the people of her hometown approached her with pitchforks and knives and torches and murder in mind, all because she’d tried to show them the world was bigger than they thought.

Admittedly, there might have been a way to show them that didn’t involve zombies.

“People don’t like a changing world,” she said. “Change hurts.”

“Can I quote you on that?”

She left Gavriel Jones at her desk, alone among the bees.

5

Every city has forsaken places: dilapidated waterfront warehouses, midtown alleys where towers close out the sky, metropolitan outskirts where real estate’s cheap and factories sprawl like bachelors in ill-tended houses, secure in the knowledge their smoke won’t trouble the delicate nostrils of the great and the good.

Alt Coulumb’s hardest harshest parts lay to its west and north, between the Paupers’ Quarter and the glass towers of the ill-named Central Business District—a broken-down region called the Ash, where last-century developments left to crumble during the Wars never quite recovered, their land rights tied up in demoniacal battles. Twenty-story stone structures rose above narrow streets, small compared to the modern glass and steel needles north and east, but strong.

Growing up in the country, Tara had assumed that once you built a building you were done—not the farmhouses and barns and silos back in Edgemont, of course; those always needed work, the structure’s whole life a long slow deliquescence back to dust, but surely their weakness came from poor materials and construction methods that at best nodded toward modernity. But a friend of hers at the Hidden Schools studied architecture and laughed at Tara’s naiveté. When Tara took offense, she explained: skyscrapers need more care than barns. Complicated systems require work to preserve their complexity. A barn has no air-conditioning to break; free the elementals that chill a tower and the human beings within will boil in their own sweat. The more intricate the dance, the more disastrous the stumble.

The abandoned towers in the Ash were simple things, built of mortar, stone, and arches, like Old World cathedrals. If Alt Coulumb fell tomorrow, they’d still stand in five hundred years. Their insides rotted, though. Façades broke. Shards of plate glass jutted from windowsills.

Tara approached on foot by daylight through the Hot Town. Kids loitered at alley mouths, hands in the pockets of loose sweatshirts, hoods drawn up in spite of the heat. Sidewalk sweepers stared at her, as did women smoking outside bars with dirty signs. Girls played double dodge on a cracked blacktop.

But when she reached the Ash, she was alone. Not even beggars lingered in these shadows.

The tallest tower lacked a top, and though black birds circled it, none landed.

Tara closed her eyes.

Outside her skull, it was almost noon; inside, cobweb cords shone moonlight against the black. This was the Craftswoman’s world, of bonds and obligations. She saw no traps, no new Craft in place. She opened her eyes again and approached the topless tower.

Sunlight streamed through broken windows. Jagged glass cast bright sharp shadows on the ruins within. Tara looked up, and up, and up, to the first intact structural vault seven stories overhead. The intervening floors had collapsed, and the wreckage of offices and apartments piled twenty feet tall in the tower’s center: splintered rotted wood, chunks of drywall, stone and ceramic, toilet bowls and countertops and tarnished office nameplates.

And of course she still couldn’t fly here, damn the jealous gods.

A few decades’ abandonment hadn’t weathered the walls enough to climb, even if she had equipment. She’d scaled the Tower of Art at the Hidden Schools, upside down a thousand feet in air, but she’d had spotters then, and what was falling to a woman who could fly? She considered, and rejected, prayer.

There had to be an entrance somewhere, she told herself, though she knew it wasn’t true.

On her third circuit of the floor, she found, behind a pile of rubble, a hole in the wall—and beyond that hole a steep and narrow stair. Maybe they hired cathedral architects for this building. Old habits died hard.

She climbed for a long time in silence and the dark. A fat spider landed on her shoulder, skittered down her jacket sleeve, and brushed the back of her hand with feathery legs; she cupped it in her fingers and returned it to its wall and webs. The spider’s poison tickled through her veins, a pleasant tension like an electric shock or the way the throat seized after chewing betel nut. A rat king lived in the tower walls, but it knew better than to send its rat knights against a Craftswoman. They knelt as she passed.

Twenty minutes later she reached the top.

Daylight blinded her after the long climb. She stepped out into shadowless noon. Clutching fingers of the spire’s unfinished dome curved above her. Blocks of fallen stone littered the roof. Iron arches swooped at odd angles overhead, stamped with runes and ornaments of weather-beaten enamel.

She turned a slow circle, saw no one, heard only wind. She slid her hands into her pockets and approached the root of one arch. It was not anchored in the stone, but beneath it, through a gap in the masonry, as if the arch had been designed to tilt or spin. She recognized the runes’ style, though she couldn’t read them. And the enameled ornaments, one for each of the many interlocking arches—

“It’s an orrery,” she said. “An orrery in your script.”

“Well spotted,” a stone voice replied.

She turned from the arch. Aev stood barely a body’s length away, head and shoulders and wings taller than Tara. Her silver circlet’s sheen had nothing to do with the sun. Tara had not heard her approach. She wasn’t meant to. “I knew you lived here. I didn’t realize it was your place, technically.”

“It isn’t,” Aev said. “Not anymore. When Our Lady fell in the God Wars, much was stolen from her, including this building.”

“I thought temples weren’t your style.”

“We are temples in ourselves. But the world was changing then, even here. We thought to change with it.” She reached overhead— far overhead—and scraped a flake of rust from the iron. “Even your heathen astronomy admits that the rock-which-circles-as-the-moon is the closest of any celestial body to our world. We thought to cultivate Our Lady’s glory through awe and understanding.”

“And then the God Wars came.”

Aev nodded. “Your once human Craftsmen, who style themselves masters of the universe, have slim regard for awe or wonder, for anything they cannot buy and sell. So deadly are they, even hope becomes a tool in their grip.”

“I’m not here to have that argument,” Tara said.

“Our temple would have been glorious. At night the people of Alt Coulumb would climb here to learn the turnings of the world.”

“Where are the others?”

Aev raised her hand. The gargoyles emerged soundlessly from behind and inside blocks of stone, unfolding wings and limbs— worshippers who were also weapons, children of a dwindled goddess. Thirty or so, last survivors of a host winnowed by the war to which their Lady led them. Strong, swift, mostly immortal. Tara did not want to fear them. She didn’t, much.

Still, preserving her nonchalance took effort.

The Blacksuits could stand still for hours at a time. Golems spun down to hibernation. Only the faintest margin separated a skeletal Craftswoman in meditation from a corpse. But the gargoyles, Seril’s children, they were not active things feigning immobility. They were stone.

“I don’t see Shale,” she said.

“He remains uncomfortable around you. Even you must admit, he has his reasons.”

“I stole his face for a good cause,” Tara said. “And he tried to kill me later, and then I saved you all from Professor Denovo. I think we’re even.”

“‘Even’ is a human concept,” Aev said. “Stone bears the marks of all that’s done to it, until new marks erase those that came before.”

“And vigilante justice—was that carved into you, too?”

“I see you heard the news.”

“I damn well heard the news. How long have you been doing this?”

“Our Lady sent her first dreams soon after our return to the city. A simple offer of exchange, to rebuild her worship.”

“And your Lady—” Tara heard herself say the capital letter, which she didn’t like but couldn’t help. She’d carried their goddess inside her.self, however briefly. “Your Lady controls Justice now. She has a police force at her disposal, and She still thought this terror-in-the-shadows routine was a good idea?”

Aev’s laugh reminded Tara of a tiger’s chuff, and she became uncomfortably conscious of the other woman’s teeth. “Justice may belong to Our Lady, but when She serves as Justice, She is bound by rules, manpower, schedules. Your old master Denovo wrought too well.”

Tara’s jaw tightened at the word “master,” but this wasn’t the time to argue that point. “So Seril uses you to answer prayers.”

“Seril is weak. For forty years the people of this city have thought Her more demon than goddess. Her cult has faded. Those who hold Her rites—rocks into the sea at moon-death, the burning of flowers and the toasting of the moon—do not know the meaning of their deeds. So we give them miracles to inspire faith. Lord Kos and His church preserve the city, but Seril and we who are Her children work in darkness, in the hours of need.”

“Some people wouldn’t like the idea of a goddess growing in the slums, feeding off desperate people’s blood.”

“We have stopped muggings, murders, and rapes. If there is harm in that, I do not see it. You have lived in this city for a year—in the Paupers’ Quarter, though its more gentrified districts—and it took you this long to learn of our efforts. Is that not a sign we have done needed work? Helped people otherwise invisible to you?”

Gravelly murmurs of assent rose from the gargoyles. Wind pierced Tara’s jacket and chilled the sweat of her long climb.

“Seril’s not strong enough to go public,” she said.

“Our Lady is stronger than She was a year ago, as She would not have been if we listened to you and kept still. Some believe, now— which is more success than your efforts have yielded.”

“I’ve spent a year chasing leads and hunting your old allies, most of whom are dead, and that’s beside the point. It sounds like you waited all of ten minutes before you started playing Robin-o-Dale. You didn’t even tell me.”

“Why would we tell you, if we knew you would disagree with our methods?”

“I am your Craftswoman, dammit. It’s my job to keep you safe.”

“Perhaps you would have known of our affairs,” Aev said, “if you spoke with the Lady once in a while.”

Moonlight, and cool silver, and a laugh like the sea. Tara shut the goddess out, and stared into her own reflection in Aev’s gemstone eyes.

“You’re lucky they still think Seril’s dead. I want a promise from all of you: no missions tonight. And I need you, Aev, at a council meet.ing soon as it’s dark enough for you to fly.”

“We will not abandon our responsibilities.”

“This is for your own good. And Seril’s.”

Aev paced. Her claws swept broad arcs through the air. Tara did not speak their language enough to follow her, but she recognized some of the curses.

“No!”

The stone voice did not belong to Aev. The gargoyle lady spun, shocked.

A gray blur struck the roof and tumbled, tearing long grooves in the stone with its landing’s force. Crouched, snarling, a new form faced Tara: slender and elegant compared to the hulking statues behind him, majestically finished, limbs lean and muscles polished, but no less stone, and furious.

Tara did not let him see her flinch. “Shale,” she said. “I’m glad you were listening. I need your pledge, with the others’, not to interfere.”

“I will not promise. And neither should they.” Aev reached for Shale, to cuff him or pull him back, but he spun away and leapt, with a single beat of broad-spread wings, to perch on the broken orrery arch, glaring down. “We are teaching the people of Alt Coulumb. They’ve come to believe—in the Paupers’ Quarter, in the markets. They pray to our Lady. They look to the skies. You’d have us give that up—the only progress we’ve made in a year. You ask us to turn our backs on the few faithful our Lady has. To break their trust. I refuse.”

“Get down,” Aev snapped.

“I fly where I wish and speak what I choose.”

“We asked Tara for her help. We should listen to her,” Aev said, “even when her counsel is hard to bear.”

“It’s just for one night,” Tara said.

Shale’s wings snapped out, shedding whorls of dust. He seemed immense atop the jagged iron spar. “For one night, and the next, and the next after that. We’ve crouched and cringed through a year of nights and nights, and if we cease our small evangelism, with each passing day the faith we’ve built will break, and faith once broken’s three times harder to reforge. I will not betray the people who call on us for aid. Will you, Mother?” He scowled at Aev. “Will any of you?” His gaze swept the rooftop gathering. Stone forms did not shuffle feet, but still Tara sensed uncertainty in shifting wings and clenching claws.

Aev made a sound in her chest that Tara heard as distant thunder. “I will swear,” she said, fierce and final. “We all will swear. We will not show ourselves. We will let prayers pass unanswered, for our Lady’s safety.”

Tara felt the promise bite between them. Not so binding as a con.tract, since no consideration had passed, but the promise was a handle nevertheless for curses and retribution should Aev betray her word. Good enough.

“You swear for the Lady’s sake,” Shale said, “yet, swearing, you turn from Her service, and from our people—you turn from the over.looked, from the fearful. Don’t abandon them!”

“And I will swear,” said another gargoyle, whose name Tara did not know. “And I.” And others, all of them, an assent in grinding chorus. Tara gathered their promises into a sheaf, and tied the sheaf through a binding glyph on her forearm. That hurt worse than the spider’s poison, but it was for a good cause.

“Broken,” Shale said, and another word, which must have been a curse in Stone. “Surrender.”

“Shale,” Aev said. “You must swear with us.”

“You cannot force me,” Shale said. “Only the Lady may command.”

He leapt off the tower. Wings folded, he needled toward the city streets—then with a whip crack he flared and glided up, and off, through Alt Coulumb’s towers.

Tara gathered her Craft into a net to snare him, hooks to catch and draw him back. Shadow rolled over her, and she cast out her arm.

But a massive claw closed around her wrist, and Aev’s body blocked her view of Shale’s retreat. Tara’s lightning spent itself against the gargoyle’s stone hide.

“I can stop him,” Tara said. She pulled against Aev’s grip, but the gargoyle’s hand did not move. “Get out of my way.” Growls rose from the other statues, obscured behind the grand curve of Aev’s wings.

“His choice is free,” Aev replied. “We will not let you bind him.”

“He’ll spoil everything.”

“We are not bound save by our own will, and the Lady’s.” Again Aev made that thunder sound. Her claw tightened—slightly—around Tara’s wrist, enough to make Tara feel her bones. “Even Shale. One child, alone, cannot cause too much trouble.”

“Want to bet?”

“Police the city more tonight. He will have no prayers to answer.”

“That’s not enough.”

“It must be.”

She remembered a dead man’s voice: you have fused a chain around your neck.

Tara’s wrist hurt.

“Fine,” she snapped, and let her shadows part and her glyphwork fade, let mortal weakness reassert its claim to the meat she wore. Her skin felt like skin again, rather than a shell. The world seemed less malleable.

Aev let her go. “I am sorry.” “Come to the meeting tonight,” she said. “I’ll see myself out.” She turned from the gargoyles and their unfinished heaven into darkness.

Somewhere a goddess laughed. Tara didn’t listen.

Excerpted from Four Roads Cross © Max Gladstone, 2016