It’s a period of turmoil in Britain, with the country’s politicians electing to remove the UK from the European Union, despite ever-increasing evidence that the public no longer supports it. And the small town of Lychford is suffering.

But what can three rural witches do to guard against the unknown? And why are unwary hikers being led over the magical borders by their smartphones’ mapping software? And is the immigration question really important enough to kill for?

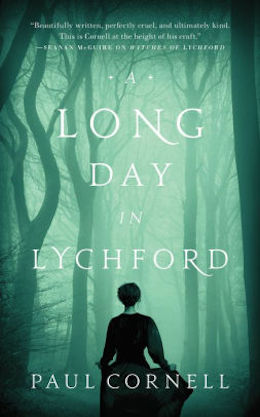

A Long Day in Lychford is the third book in Paul Cornell’s Witches of Lychford series, available October 10th from Tor.com Publishing.

Chapter 1

Marcin Przybylski was lost, and the voice in the cab of his lorry wasn’t being much help. “At the roundabout, take the third exit, and continue…”

He stared into the darkness of the tree-lined road ahead. “Where’s the roundabout?” he asked his phone, helplessly. The phone was attached to a bracket on the dashboard, and illuminated as if to underline its importance. Because right now it ruled his life. Mr. Ofgarten, who right now would be asleep in his comfy bed, had some sort of beacon attached to each one of these phones. If, when he woke up and checked his enormous tablet over his delicious morning pastries, one of those drivers was not anywhere near, in this case, the brand new Tesco distribution centre at Pilning in Gloucestershire, however you were meant to pronounce that… well, there would be a stream of German obscenities down the line. It was said that to be more than twenty minutes late meant automatic dismissal. At least then Marcin could tell him what he could do with his smoked sausages.

He’d got to the Oxford distribution centre for Sainsbury’s with no problem. That was second nature by now. It was the combination of this new location and this “brilliant new crowdsourced navigation app” that Ofgarten had installed that was foxing him.

A sign loomed ahead in the summer night. “Lychford,” he said to the phone.

“I do not recognise the location,” the phone replied.

“Of course not.”

“I do not understand the instruction.”

“Oh, go to hell!”

“Changing route now.”

“No! Stop!”

“Stopping now.” And the screen showed the moving circle that indicated it was waiting for further instructions.

Marcin managed to avoid bellowing at it, worried that might dig him in deeper. He was passing a new housing estate on the edge of this Lychford, woodlands on the other side. Was there anyone around here he could wake up at this time in the morning to ask for directions? How willing to answer their door would they be? And he didn’t have much English. Did he trust his phone to translate for him?

Suddenly, the light seemed to change a little, and he jumped, worried that, despite being used to the night shift, he’d fallen asleep. But no. Still the woodlands. Maybe that had been lightning? Or was it getting light this early?

“Turn left,” said his phone. Ah, it was back!

Only of course there didn’t seem to be a… no, what was that up ahead? He couldn’t see it properly, did he need glasses? The road seemed to suddenly—!

Marcin had to haul on the wheel as abruptly, impossibly, the road he was travelling on turned almost at a right angle and headed upwards into… what the hell was that?!

“I do not recognise this location!” yelled his phone. And it kept yelling it. As Marcin and his lorry skidded uncontrollably into what seemed like… nothingness.

Autumn Blunstone woke up, and gradually realised she was lying face down, fully clothed, in her own bed, upstairs at her magic shop, Witches, in the market town of Lychford, in the Cotswolds. These facts came to her one by one, introducing themselves politely.

The sun was already up. A cool breeze was ruffling the curtains. It was… really early still. Why was she awake?

Autumn felt… bloody awful. Not actually entirely… hungover, not yet. It was like the hangover was literally hanging over her, waiting to expand to its full dimensions, but had first just wanted to knock on her door to tell her it was getting ready to do its thing. We have a delivery for you, it was saying, and we will not hand it to a neighbour, but intend to unpack it in your every special place.

Knocking on her… no, someone was actually knocking on the door downstairs. Really quite loudly and urgently. At this time in the morning. And there was distant music somewhere out there. The duff duff duff of dance music. What was that about?

Autumn shouted something incoherent, reached out to find her robe, realised she didn’t need to and fell out of bed.

At the door she found PC Shaun Mawson, in uniform and definitely on business. In the air, from somewhere behind him, faded in and out that beat of some distant, ongoing rave.

“Miss Blunstone,” he said, “can I come in? It’s urgent.” It must have been for him to call her by anything other than her first name, or more usually just a shy nod. Shaun was the son of Autumn’s elderly employee and supposed mentor in the ways of magic, Judith, but he shared none of his mother’s bloody-mindedness. Thank God. He turned down the offer of tea, and made Autumn sit down in the kitchen.

“Is someone… dead?” she asked.

“We don’t know. That’s why I’m here.” He got out his notebook and pen and held up a hand to gently halt her questions. “Let’s start at the beginning. Can you remember much about last night? Can you remember where you got to?”

Great question.

Worrying question.

Why had he asked her to sit down?

No, come on, concentrate on the question. Where had she been last night? Autumn had always said there was a pub in Lychford to suit her every mood. If you wanted the good company of builders and town councillors, there was the Plough. If you wanted to meet people who were just passing through, or to sit and read quietly, there was the Market Hotel. If you wanted noise, youth, and the offer of drugs in the toilets, there was the Randolph. And if you wanted a fight, there was the Custom House. That was it for the pubs of Lychford these days. A couple had closed down recently. When Autumn had been a teenager, there’d been seventeen. Over the years, her range of options had narrowed, but, neatly, so had her range of moods.

“I think I was at… the Custom House?”

The Custom House was the sort of pub that the town council kept wanting to find a good reason to close down. The dusty whitewash on the outside gave one a clue that here was an inn the carpet of which could have been the subject of a TV nature special by David Attenborough. As you headed for the bar, your footsteps crunched. The walls inside were bare, the cloth on the pool table ripped, though people still played on it. The fruit machine’s soundboard had once had a pint tipped into it, resulting in strange, muffled, warblings. However, the landlord, Malcolm, kept the beer pipes clean, and for the Custom House’s clientele, that was the only required saving grace. After you got to know people, the décor became a feature, not a bug.

But yeah, there were often fights.

“Why did you decide to go there?” Shaun’s tone suggested that no nice young lady would. Autumn tended to end up at the Custom House having had a couple of drinks at one of the other pubs, become slightly angry with something someone had said there—but not enough to want to cause a fuss—and thus decided to move on. Her light complexion, what her best friend Lizzie had once called her “had clothes fall on her accidentally” sense of style, and, she supposed, the fact that she’d always been around, all distracted from the fact that she was, as they said these days, a person of colour. So she overheard things in those other pubs: perfectly nice people who’d never use the N word still saying “chinky” and, incredibly, “pikey”; people on her own social level knowing they were being risqué when they’d had a few, making jokes that started with “Jewboy and Mick walk into a pub.” When she’d been younger, she’d always spoken up at that point, and had been pleased when there’d often been whoops of applause rather than dismissal. Some of it was “oh ah, here she goes again,” but some of it had always been that feeling that she was to be congratulated for speaking up for “her own people.” Not that she knew, apart from her extended family in Swindon, any of her own people. Not since her Dad had passed away. She was literally the only non-white person in the entire town. That, she suspected, was the only circumstance in which you’d get that welcoming reaction, when the majority thought of you as the sole representative, and therefore harmless. Of course, in Lychford, there were also Sunil Mehra and his employees, but she’d never felt they had much in common. Sunil was part of the “reception for the Prince of Wales” crowd in this town, who’d probably see himself as “one of them,” while she was… whatever class it was that owned magic shops.

She was aware that, as she’d gotten older and still overheard things in pubs, she’d stopped speaking up so much. Because when you stopped being a teenager, you started feeling less sure of yourself, and not everything seemed like it was life and death. And she liked fitting in. She was quite popular, wasn’t she? And these were good people, really. Really. But it hadn’t eased off like she used to think it was going to. It had gotten worse. It had gotten more normal. The ones being “risqué” seemed to find it easier to say.

And then last year, that bloody year.

The walk through the marketplace on the day after the Brexit vote had been like something out of a science fiction movie. And that was saying something, coming from someone who was getting used to seeing magical beings. Which of these people, she had thought, looking around herself on that market day, had voted to saw themselves off from the rest of Europe? Which of these people, in their heart of hearts, wanted a Lychford that was “just like it had been in the 1950s”? Which of the shops she spent money in were owned by people who wanted the full emulsion white paint job, corner to corner, maybe without even having thought about it enough to know that was what they wanted? Which of the coffee shops contained people who were cheering inside today? She’d never know, because this was Britain, after all, and nice people don’t talk about anything that might cause trouble, and so all that day the town had been weirdly silent.

She’d gone down the pub that night, and people hadn’t talked about it there, either, but Autumn had overheard things, a lot of things, and that had been the first time she’d found herself going down the road to the Custom House. In the weeks and months that had followed, after the election, she’d found herself going there more and more. She’d talked with Lizzie about how she felt, and that always made her feel better for a while, like going on the Women’s March in Bristol after Trump’s election had made her feel better for a while. But the trouble with talking about this with Lizzie was that Lizzie would never understand how much these things made Autumn feel like an outsider in her own town. It had been months now, and she still couldn’t find a way to haul herself out of the pit that social media dropped her into every morning. She looked at the future, and for the first time in her life, the way ahead looked uniformly grim. There were such incredible things in people’s lives now, like photos from space probes around Saturn, and such incredible things outside those lives, the magic only the three of them knew about, and yet still, still, these tiny bloody people with their pent-up little bloody fears—! Even if she could have put it all into words, she couldn’t be sure Shaun Mawson would ever understand.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t know why I went to the Custom House.”

“Did anything… particularly stressful happen to you yesterday? I’m wondering how worked up you were when you got there.”

Yesterday had been a long, sweaty summer day, which had seemed to gather up anger within itself, ready for a storm. And, oh God… yeah, she remembered now, the storm had broken. During that day, she had ended up having the row she was always going to have. And, horribly, it had been with the mother of the police officer who was facing her now. It had been with Judith.

They’d fallen into it by accident. The old witch of the hedgerow, as Judith liked to style herself, both mentally and in terms of grooming, had sat permanently behind the till that day, just like most days now, glaring at any tourists who might happen to come into the shop, setting quizzes about the occult history of Gloucestershire in the sixteenth century to any of them who might offhandedly try to strike up a conversation about crystals or the healing energy of unicorns. It was like Autumn was keeping a troll behind the counter, in every sense of the word. She had wondered hopefully, in the last few months, as Judith’s attitude to people had got worse, if Judith might seem like the more challenging end of the real ale spectrum, that people might start to say that was the real thing at that magic shop, that, horrible as it tasted, it was the genuine experience. But no, after the third tourist yesterday had left without buying anything, at a speed which left the shop bell bashing against its hanger, Autumn had finally dropped the idea of monetising the degree of difficulty her employee presented to the world. “Okay,” she’d said, “you can’t keep doing that. What with Brexit, I need to start making some sales here—”

“What about it?”

Autumn had realised that, at the end of a tiring day, she had finally let slip what she had avoided talking about with Judith all this time. She had said the magic word. Ironically. Still, she knew that Judith’s grasp of economics was usually that of an elderly aunt who every year tried to bet five pence each way on the Grand National.

“Any supplies I get in from Europe are now literally worth their weight in gold, and given everything that’s happened this year, the council will be putting the rates up.”

Judith had made a dismissive sound in her throat. “Things’ll get better.”

Autumn had paused, wondering if that had meant what she’d thought it had. Judith had made grudging eye contact, then looked away. And Autumn had recalled how, according to the polls, there had been a direct correlation between one’s closeness to the cemetery and how willing one was to mess up the future for generations to come. It had occurred to her that it would be just like Judith to have done what a number of the folk down the pub seemed to have done: to have taken any yes/no question from any government as an immediate reason to burn down their own house and everyone else’s. “Okay, you got me. You’ve been working hard today to separate my shop from its customers. I’m interested in how you feel about separating other stuff. Which way did you vote?”

Judith had glared at her. “None of your business.”

Which nobody on the Remain side ever said. It was only the Leavers who wanted to hide it. “Oh no. You did, didn’t you?”

“Vote’s private. That’s democracy, isn’t it?”

“But you’re not proud of it?”

“I don’t talk about politics or religion.”

“You’re a witch, who works in a magic shop and, like the car sticker would say, your other apprentice is a vicar.”

“I don’t talk about politics. Stop going on. Do you want a cuppa?”

Which had been the first time in the history of their association that Judith had ever offered to make the tea. The enormity of this distraction might even have worked, if Autumn had been willing to let it. With the sun getting lower in the shop window, the row might have faded and Autumn might have decided to let it go, let her go, let her go back to her house and annoy her neighbours instead. As the song so nearly put it. But that had been the moment, Autumn remembered now, the moment she’d realised something huge about the situation she and Lizzie were in, something that had felt in that second like sheer complicity on her part. “Oh my God,” she said. “That’s what you’re teaching us to do.”

“What?” Judith had looked at Autumn like she’d gone mad.

“We’re defending the borders of this town. We’re here to deter the outsiders. That’s what we’re all about, isn’t it? That’s what we do.”

There had been a long silence. There had been, even then, Autumn thought now, things Judith could have said.

But instead, Judith had slowly got to her feet. “Do you want me to keep on working here, then?” Those merciless old eyes had fixed on Autumn. Judith had done what she always did. She had boiled down the complexities of a situation to some ridiculous basics.

Autumn had wanted to say of course she wanted Judith to stay. She really had. But in the heat of that moment, she hadn’t been able to get the words out. Instead, she’d said nothing.

After a moment, Judith had picked up her bag from under the desk, and headed for the door. Autumn had wanted to call to her before she got there. She had not.

So Judith had left, and the door had closed gently behind her.

It had taken Autumn a few minutes after Judith had left to move at all.

When she had, it had been fast. She had been shaking with emotion. She had locked up the till, locked up the shop, slammed the bolts… and headed down to the Custom House.

“It had just… been a long day,” she said to Shaun now. “I’d had some problems with one of my staff.”

He carefully wrote that down. What was going on here? She felt like she’d just somehow incriminated herself. “Okay,” he said. “Was there any trouble when you were in the pub itself?”

Autumn recalled that she hadn’t been the first to set forth across the crunchy carpet of the Custom House last night. Her heart had sunk, in fact, when she’d seen who’d gotten there before her for early doors. It had been Jenker. Keith Jenkins, he was properly called, a taxi driver who’d married someone in the Backs. The Custom House was his local. Earlier that summer, when Autumn had come in complaining about the heat, he’d said something about her working on her suntan. At the time, she hadn’t been quite sure whether or not he’d meant it literally, and he’d maintained eye contact, kept that innocent grin on his ruddy, aye aye, here’s the life and soul of the party face. She couldn’t help but be wary of him after that, though, and yeah, she’d overheard things.

“Hello hello!” he’d boomed yesterday night. “Here comes trouble.”

Which would normally have been the sort of greeting she loved. But not from him. And especially not after the day she’d had. She’d nodded to him, she remembered, and ordered a pint of 6B. It would have been impossible, in the circumstances, not to talk to him, but the last thing she’d wanted to talk about was what had happened with Judith and the guilt and anger that were wrestling within her. He’d tried the normal, harmless, topics, such as football and the weather, and she’d nodded along, barely listening to his replies. With anyone else, on any other day, she would gleefully have raised the subject of the weirdness of her work at the magic shop. She liked to present what she did, at least the public part of it, to her pub friends in all its eccentricity and have them tease her about it. But she couldn’t do that with Jenker. She wouldn’t make herself sociably vulnerable to him.

After a couple of drinks, however, she’d taken something he said for a starting point for a conversation that swiftly turned into come on, did he feel okay with how things were now, when you couldn’t say anything on Twitter without some fascist, some, I mean, literal fascist, someone who if you asked “are there any fascists here?” would put up his hand and say “actually…”? It had turned out Jenker wasn’t on Twitter, and thought people who paid too much attention to the Internet were a bit… he’d made big boggly eyes at her.

Where had it gone from there? Oh God, she was starting to remember. Shaun the police officer was actually quite good at this interviewing thing, wasn’t he?

After three drinks, one of which Jenker had bought her, and she’d suddenly started to wonder if he thought she was coming on to him, but no, that moment had gone past without comment, they’d started to seriously argue about what Brexit was going to mean to the economic future of Britain. He kept cutting her off and saying “nah,” while making points she found she didn’t have the information to hand to come back about. If you were a “crap farmer, not a good farmer” you had reason to vote to stay in, he said, but fishermen had a good reason to vote out. Then Autumn said what about wanting to keep all the brown people out, and he’d said it wasn’t about the brown people, he was mates with a lot of brown people, like her, no offence, it was the bloody Poles and the whatever they were from central Europe, who couldn’t speak English, taking their jobs, bringing their own shops over here and their foreign muck into our supermarkets. If she thought it was about brown people, that was where the chip on her shoulder had come from. No offence. Here, Autumn had been on steadier ground, at least in terms of data, and she’d held her own, and had actually said out loud that she felt she was one of those people too. Every sort of those people. He’d said, what you? You’ve been here longer than I have! He’d started holding up a finger for his interruptions, and had said they should have another pint and blimey love, you can talk, can’t you, you and me must have been separated at birth, maybe I had a touch of the tar brush too, ’cos you’re not full on, are you, you’re half and half, so I don’t see what you’ve got to worry about, and she’d been about to… explode? Yeah, hopefully she’d been about to do that rather than force a laugh, when one of the many, many people who had somehow filled the pub around them, some of whom were now looking on in glee or embarrassment, had spoken up.

Oh. Oh my God. She remembered now.

This was him. She remembered his face. An old lad, in his seventies, newspaper under his arm. A ruddy, drinker’s face, balding, a fleck of grey stubble on his chin. He was so important. Why was he so important? What had happened to him?

“There… wasn’t really any trouble,” she said to Shaun. “Bit of a row.”

“Do you remember anyone in particular being there?”

She mentioned Jenker. But okay, Shaun probably had in mind this… weirdly important guy she’d just remembered. “Someone told me his name was… Old Rory?”

“Rory Holt.” That seemed to be the box he’d been wondering if she was going to tick. “Did he say anything in particular to you?”

Yeah. Yeah, he had, now Shaun had made her think of it. And it had been a terrible thing. It would have appeared in her memory, sometime today. It would have popped up, to bring her crashing down. Like it had halted her in her tracks now.

She could see him in her mind’s eye now, a little grin on his face as he’d said it. “Bloody good idea.” That’s what he’d said.

“What is?” she’d replied.

“A wall,” he’d said. “Trump’s got it right. We should build one too. Keep ’em all out.”

Which had gotten laughs, because come on this was still Britain, and nobody, whatever their politics, flew a flag for the most ridiculous American of them all, and that had come out of bloody nowhere. But it had left Autumn speechless. It had been a one-two punch with the awkward anger at what Jenker had just said.

She had stared at the old man. He’d met her gaze, challenging her. He hadn’t looked away. His gaze said, What the hell are you doing here in my sight? Did you think we were equal? This is my home. Not yours.

Jenker had tapped her on the shoulder. “Old Rory’s been reading the Internet too much,” he’d said, and made the boggly eyes again. “Do you want another?”

Was that how furious the look on her face had been, that he’d felt he’d needed to distract her?

What had happened next? She remembered leaving the pub… didn’t she? Had that been soon after? Had she had that next drink and lost track? Had she lost track of Rory Holt too?

“What happened next?” asked Shaun.

“I… I really don’t know. Could you tell me why you’re asking me all this?”

Shaun pursed his lips.

Like a lot of elderly people, Judith Mawson didn’t need much sleep, and thus tended to get up early. She would put the television on in her kitchen and watch something stupid before the news as she made a very early breakfast, these days usually consisting of whatever half-arsed cereal the doctor said she needed to force down for the sake of her… heart, usually, but pick any organ. Like they said, eating healthy food might not help you live longer, but it certainly made you feel like you were. In the last six months or so, as she went through her usual ritual, she’d find herself glancing at the stairs, always thinking she’d heard a voice, when actually she hadn’t.

“Stupid,” she whispered to herself. “Soft.”

Judith had got used to living with the spiteful ghost of Arthur, her husband, or rather, a curse that had taken his shape. The spectre might have been evil and cruel, but at least he’d been company. She was still trying to find a way to deal with the lack of another presence in the house, and thus, for the first time, having to completely accept that the real Arthur was gone. It was a strange, attenuated sort of grieving, made worse by Judith only having two people she could talk about it with: her apprentices, Autumn and Lizzie. Well, make that one person, after yesterday. The thought of it made her stop, with the cereal packet in mid-air. She had to take a moment to control her anger, as she had so many times before finally getting to sleep last night. Of course that stupid girl had wanted her to stay on at the shop, she just hadn’t been able to bring herself to say the words. And that wasn’t bloody good enough. Before she set foot in that place again, before she let Autumn resume her training, she would want, at the very least, an apology. And more money. And… whatever bloody else that stupid, stupid—!

Judith stopped herself. Her doctor probably wouldn’t approve of her getting so worked up, and what for? It had only been the sort of thing young folk did, with their emotions flooding all over the place like spilt milk. She’d lost sleep about it, but so what? She wouldn’t go in today, get an afternoon nap, let the stupid girl come to her.

For the umpteenth time, she put that matter to the back of her mind. What was worrying her more right now was this note she’d found attached to her fridge by a magnet. It made no sense. The note said:

Remember that your parents are dead, you great fool.

Which was ridiculous, because Judith’s parents still lived next door like they’d always done. Only… no, that wasn’t true, was it? She clicked her tongue, annoyed with herself. That was her getting old. Joyce who had that horrible laugh lived there now, with her parakeet. So… Judith’s parents must have moved out, but… they’d have told her where they were going, wouldn’t they?

They must have moved out.

Where?

This bloody note, making no sense. Nothing of magic about it, either. It hadn’t just appeared. Someone had, quite normally, written it and put it there.

The weirdest thing about the note was, it was in Judith’s own handwriting.

The Reverend Lizzie Blackmore groaned, and threw out a hand to hit her clock radio. It was only when her hand had connected three times to the button atop the radio, and she had only succeeded in switching it on, and it had filled the room with the soothing really very early morning sounds of BBC Radio 2, that she realised it was not actually 6:30 a.m., but a whole hour earlier. She switched it off, and then realised what had actually awoken her. The sound of distant music was wafting through her open window. Duff, duff, duff, dance music, so far away you could only hear the beat, then the beat changing, then back to the previous beat. She got up, stumbled to the window, and closed it. That wouldn’t be uncomfortable. The Vicarage was cool in summer, if bloody freezing in winter. But she could still hear the beat, like a distant tapping. It was locked into her consciousness, specific and now just at the volume that made your ears listen out for it. Had it stopped? No, there it was. Had it stopped now? Nope.

She went back to bed and listened for about ten minutes to the changing beat, without wanting to. If it would only stay the same for a minute or two, she could have fallen asleep to it. She really didn’t feel much like bloody dancing. Finally, she got up, put on her dressing gown, and grabbed from her bedside table the item which was now ruling her life. She’d gotten the Exercise Tracker for herself as a New Year’s present, following that rather traumatic Christmas. The little electronic sadist was already making a bit of a difference to the size of her arse. Then she headed for the stairs, intending to make a cup of tea. She could spend this extra hour sending out a few emails, getting ahead of the day’s problems. And perhaps she could play Overwatch for a bit.

She was surprised, and then alarmed, as she walked blearily down the stairs, to hear that the kettle was already boiling. She stopped, remembering that the burglar alarm was still below her in the hall. It was only relatively recently, after she’d been bathed in the water from the well in the woods, and become able to see the magical powers surrounding and threatening Lychford, that she’d even started turning it on. She couldn’t get to the emergency button, but her phone was charging upstairs. She’d started to carefully make her way back up when a voice called from below. “Do you want a cuppa?”

She recognised the voice, and the way it had just said the most ordinary of sentences as if it was learning a foreign language, and was first relieved, then angry.

She marched down the stairs and into the kitchen to find Finn, Prince of the Fairies, appreciatively watching her kettle boil as if it was some sort of modern art installation. “What the hell are you doing here?” she said.

He turned to look at her, not his usual jovial self. “Something strange is happening. I’d have gone to see, you know, the other one—”

“You mean Autumn? Your ex?”

Finn’s supernaturally handsome features creased into the most gorgeous frown Lizzie had ever seen. It really was hard to stay angry with him. Which was, in itself, worrying. “I can’t be expected to remember everyone. You people keep… reproducing. And then I look up from whatever I’m doing and you’ve had a millennium and I’m like ‘where does the time go?’ and—”

“Is there any point in asking how you got in? And yes, now you’re here, I do want some strong black coffee, thank you.”

Finn, as if he was following the most exotic process of preparation, and looking to her for guidance every other moment, made just that, and for himself poured hot water onto a tea bag it looked like he’d brought along, because Lizzie was pretty sure she didn’t own any that glowed green. “I got in by walking down past the walls, which was really hard, as expected, because the Vicarage still has about it some of the old shapes of protection”

“I thought that in Lychford the vicar and, you know, magic people were always on the same side?”

Finn took a long drink from his mug, and glowed slightly green himself for a moment. “You church folk are indeed usually allies with the wise woman of the town, but the nation of my father, we’re not always friends with humans. This is reasonably easy to grasp, surely? Human beings still have different nations. You have borders even from your allies, right?”

“True.”

“So those who built the Vicarage made its shape to defend against people like me slipping in and out without a lot of effort. Hence this.” He pointed to his mug. “Keeps my strength up. Like I said, I’d have gone to see one of the other two for preference, but the old one’s got some serious ‘keep away’ hoo-hah round her place these days, and Autumn’s got a guest over.”

“Oh?” Lizzie realised she’d put the wrong note in her voice and changed it to a more neutral “Oh.”

Finn raised a frankly delightful eyebrow. “How are she and that new lad of hers doing?”

“How do you know about that?”

Finn just pointed at himself.

“Has that question got anything to do with the sort of company she’s got this morning?”

“Not sure. Probably not. So how are she and Luke doing?”

Lizzie noted that he knew Autumn’s boyfriend’s name. “They have their ups and downs, but they’re still together. He’s off on some teaching thing up north.”

“Probably for the best.”

“Why?”

“Because of this strangeness that’s been going on. As I was about to say before I was so rudely interrupted, today it wasn’t just the shape of this place that made it hard to get in here. Something has happened to the borders. Leaving fairy and getting into Lychford is normally just about taking a step here and a step there. This time it was like stumbling down a hill. I felt like I’d crash any moment, and I don’t know what crashing would even involve. When I get back, everyone’ll be yelling about this.”

“That is worrying. Okay, thanks for—”

“But that’s not why I came here! I only found that out on the way here! And now I think of it, maybe the two are connected, because this is damnable, this is unconscionable, this I was sent from the court of my father with urgent diplomatic condemnation concerning!”

Lizzie held up her hands, amazed at the sudden fury which had taken him over. It was as if he had remembered that he was supposed to be officially angry, and in that moment, took on that emotion for real. Once again, she’d been reminded that though a fairy like Finn might resemble a human being, he was actually very different. “What?!’

“What,” yelled Finn, pointing out of the window in the direction of the repetitive beats, “is that bloody music?”

Lizzie could only shrug in agreement. “I know.” Then she realised she was representing possibly the entire human race in an official diplomatic negotiation with another… species? If that was what fairies were. Not a situation she expected to encounter while still in her dressing gown. She made herself straighten up and adjusted her robe. “I mean…” she said, more carefully, “I don’t know.”

Finn sighed. “I now have a new winner for our ‘stupid things humans say’ board.”

“Do you really have a—?”

“What you’re trying to say is: you don’t know what that music is either?”

“I know what it is.” And before he could scream in frustration, Lizzie quickly explained the concept of illegal raves, from the perspective of someone who’d last gone out dancing two decades ago.

Finn seemed relieved to at least have an explanation he could take back to his father. “Well, normally I’d be all for that, and good work there with the mind-expanding drugs, because at least someone here’s trying, but how is the sound of it getting into fairy? We’ve got stuff to do, you know. We need the sleep of ages under the hills. We can’t be having with dush dush dush all the time.”

“So the dance music is… keeping the fairies awake?”

“That’s what I just said. Try to keep up.”

“Well, our local police, such as they are, will be out trying to find it, I should think.”

“Probably, though I’ve seen a few of them this morning doing other things besides. But what worries me most is, since I got here I’ve had a bit of a look for where the music’s coming from, and I can’t find it. And I have the nose of a bloodhound. In my pocket.” He took something that Lizzie really hoped was a felt novelty of some kind from his jacket and showed it to her. “So your police won’t be able to. You put that together with the borders getting messed up, and it’s big trouble for everyone.”

“You’re right. I’ll tell the others.”

Finn seemed satisfied. “Excellent. This is what the three of you are for.” He threw back the remains of his tea, then glanced suspiciously at Lizzie, carefully washed out his mug, and retrieved the tea bag. “Good luck with it. Now I have to go home and listen to everyone at court getting worked up all over again. Let’s hope you can deal with it before that boils over into, you know, the collapse of reality. Or whatever.” And with a gesture that seemed somehow dismissive as well as functional, he vanished. Then there was a sudden clonk sound from somewhere inside the walls, and a cry of pain, and then a motion of air that Lizzie somehow knew meant that now he’d actually gone, on the second attempt, and that the Vicarage’s old defences were still good for some things.

Lizzie’s first impulse was to go and see what sort of company Autumn had at this time in the morning, but no, Judith was who she should go to find.

She went back upstairs, pleased at having added an unexpected flight of steps to her fitness tracker’s records, dressed, then headed off to Judith’s house.

As she walked up the hill from the marketplace, that distant sound of dance music was still drifting over the town. It was indeed weird that, if that was an illegal rave, the police hadn’t found it and closed it down by now. Something that loud couldn’t be legal, could it? Wouldn’t she have had a warning letter through her door, or something?

There didn’t initially seem to be anyone at home at Judith’s house. But that was often the case these days. Lizzie knew Judith had been grieving in a manner that was, quite possibly, unique in all of human history. Lizzie had been doing her best to help, because comforting grieving widows was very much part of her skill set, but Judith had been, as expected, one of her more challenging subjects. The old lady’s desire to not say anything to anyone about anything unless it was somehow offensive had reached a new intensity in these last few months. It took a bit of work for anyone dealing with her to realise that she’d changed, because she now bore an entirely different burden than the one she’d borne for years before. And that burden had been made worse, of course, by its own potential for change, that someday Judith might bear no burden at all. The weight on her shoulders had grown to be part of her, had informed the malice that often seemed, to those who didn’t know her well, to be what kept her going.

At Lizzie’s third ring of the bell, the door opened. Judith stood there, looking even more grim than usual. “I was just about to come and find you,” she said. “Summat terrible has happened.”

“I know—” began Lizzie.

“No you don’t,” said Judith.

Excerpted from A Long Day in Lychford, copyright © 2017 by Paul Cornell.