“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.”

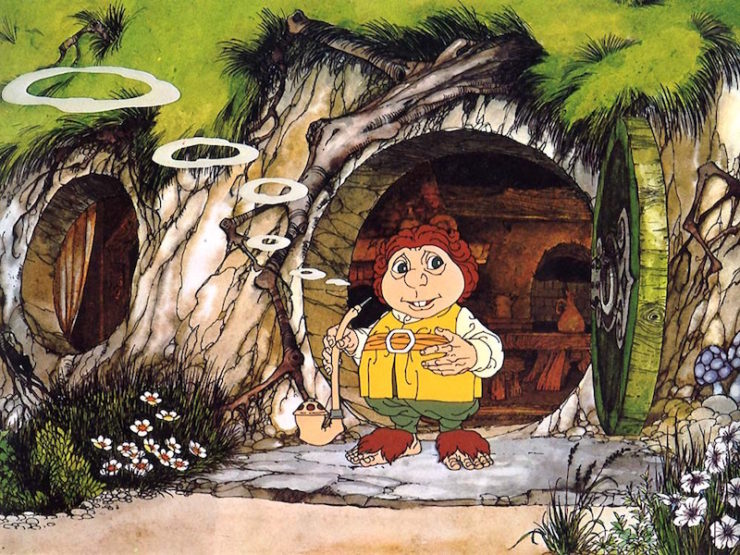

How many of us can recite this line from memory? I admit, I get tripped up in the details, but the first sentence is gold, and the image it conjures up is even better. For me, it’s one part Peter Jackson, one part Rankin/Bass (pictured above), one part the way I imagined a hobbit-hole before I’d seen any movies. Tidy. Cozy. Warm. Wood-lined. Part of a tree, part of the earth, close to all the things I cared so fiercely about when I was a small kid hearing The Hobbit read aloud for the first time.

I have been reading a book about a house—of course, a book about a house is never just a book about a house—and it has left me feeling a little scraped and raw. It’s the kind of book that starts out feeling like a rollicking adventure and then burns away layers until you remember that every house has seen (or will see) things good and bad, seen life and death and the little moments and the large. Fictional houses can seem like havens because we only get to spend a little bit of time with them. But that time, however brief, can be hugely influential.

For me, it didn’t start with hobbit-holes. It started with The Wind in the Willows—specifically, the edition illustrated by Michael Hague, in which everything is rich and saturated and looks as welcoming and comfortable as a well-worn velvet sofa. I haven’t even seen a copy of this book in years and I can still see Mole and Badger and Rat and the rest; I am still shocked that I have not yet cross-stitched the words “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats” and hung them on the wall. (Do I regularly mess about in boats? No. Did I when I was small? Yes, whenever given the opportunity.)

The warrens and homes of The Wind in the Willows were cluttered, but perfectly so. Things had places they were meant to go. Wood furniture, things hanging from the rafters, large tables and roaring fireplaces—put them all in my house.

(Some may have loved Toad Hall more, but to a kid, it was the place you’d be nervous about breaking something. No, it’s a den for me.)

And a den is very like a hobbit-hole, in some ways. Cozy, warm, practical, built for meals and guests. When I got a little older, though, I discovered the other place in Middle-earth that I desperately wanted to live: Lothlórien. Living in the trees! I had never even heard of Swiss Family Robinson, yet was obsessed with treehouses, with the idea of being up, up, up among the secret branches, the ones that in normal trees were too flimsy to hold much weight. Magic trees were clearly different.

But the logistics didn’t really matter. It was just the idea of this golden magical wood that somehow, wise and clever like the elves, had everything a person could need. I imagined it sort of like the forest in my childhood copy of The Twelve Dancing Princesses, all golden and beautifully impractical. I never got around to imagining the elves’ actual homes. Just the trees. Trees that were home—no matter how distant Middle-earth seemed, that I understood.

In elementary and middle school, I encountered a lot of houses that were both basic and beyond my understanding. My idea of New York City was a mash-up of contrasts: the apartments of All-of-a-Kind Family (five sisters in one room!); the expansive, incredible museum in From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler; the magical New York in So You Want to Be a Wizard. I loved The Westing Game and had absolutely no idea how to imagine an “apartment house.” I knew it was on a lake, but I had no idea how big a lake could be. I imagined a sort of tower that was also a house, a hotel that had house-like characteristics. I can still almost see how wrong I was.

And then there was the concept of the beach house. Some of you may have met this concept in a normal sort of way: by being in one. I discovered it in William Sleator’s Interstellar Pig, in which a kid on vacation at the beach meets some very interesting neighbors who are playing an even more intriguing board game.

Beach houses—the real things—never lived up to my youthful imaginings.

Fantasy is full of homes that a reader may or may not imagine as the author saw them. The house in The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, which I envisioned full of libraries and animals, a mountain house that was isolated but comforting, cozy and stern at once. The weyrs of Anne McCaffreys’ dragonriders—how did we picture those? What did they look like? Why does my brain hold onto a single image of a hallway from a Melanie Rawn book when I can’t remember which book, or why that location might be important?

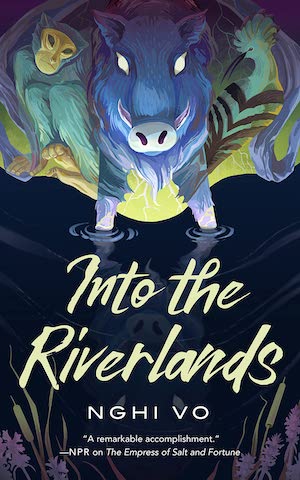

Buy the Book

Into the Riverlands

Somewhere in all of our heads is an utterly feat of impossible architecture, all of these places connected, like an M.C. Escher drawing of towers and forests and clean stone walls.

Where I wanted to live as a teen, though, was slightly simpler: a house that was a cross between the Addams Family house and something you’d find in an Edward Gorey drawing. There is no other explanation for how old Victorians and their ilk danced into my head and settled there. They are not hobbit-holes (though you could make one just as cozy). They are not tree-forts or railroad apartments. But they are still my brain’s highest idea of a perfect house—at least of the kind a person can have.

(Of the magic kind, there is nothing better than Howl’s castle.)

There’s probably a lineup of houses in your head, too. They aren’t always easy to access; I had to think more than I expected about where I had found all my ideas about home and comfort and an ideal use of space. (And this is only what lodged in my psyche early; there’s a whole other list of houses and castles and dens from my more recent years of reading.)

Like so many other things in books, these concepts seep in when you aren’t looking for them. A book is a story about how even the smallest of us can have important roles to play, but it’s also a story about what matters to different people and where they feel safe. How to live comfortably, and how that can mean so many different things. (Let us not forget the raft people of Earthsea!) Some want to be close to the earth. Some want to peer into the distance from the tops of trees. And some make mountain homes far up in the cold north that are still the warmest places of all. What we read shapes how we see the world, what leaps out and what fades back—and colors how we want to live in it.

What does your magical architecture look like?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.

Just a minor correction. The picture above is from the 1977 Rankin/Bass cartoon, not Bakshi.

@1 – Thanks for that! It was actually my mistake – I wrote one and meant the other.

I grew up on Stately Wayne Manor from Adam West’s Batman, and while I do not especially need the house, I totally want the Batcave. And the Batpoles. Likewise, I do not need Disney’s Beast’s castle, but that library….

One thing, though. That is a Rankin/Bass hobbit-hole up top, not a Bakshi hobbit-hole. (Which is, to my mind, as it should be; as I have said elsewhere on this site, that version is definitely my Hobbit.)

[ETA: And crossposted….]

All-0f-A-Kind Family shout out, yay!

Yes, Toad Hall does not sound comfortable…need to read The Wind in the Willows again–it’s been decades.

Hmmm….Rivendell because I could find a corner to myself, the Burrow, and the Room of Requirement (the kitchen would include what I my ideal kitchen would include: an electric range, small fridge, plate racks, place for cook books…and a stand mixer).

I still want a hobbit hole. There’s gotta be a way.

A hobbit hole with a secret passage that goes an inexplicably short distance and connects to Rivendell. And with a big library.

It’s a very much each-to-their-own topic here but, as a kid, I was absolutely enamored of Captain Nemo’s Nautilus in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. A comfortable underwater home that goes places unobserved? Yeah, I still want that one….

Love this! It was also Wind in the Willows for me, and Tom Sawyer. Growing up by water in the woods had something to with it.

I have a suspicion that Tolkien had Mrs Tittlemouse on n mind:

Once upon a time there was a wood-mouse, and her name was Mrs. Tittlemouse. She lived in a bank under a hedge. Such a funny house! There were yards and yards of sandy passages, leading to storerooms and nut-cellars and seed-cellars, all amongst the roots of the hedge. There was a kitchen, a parlour, a pantry, and a larder. Also, there was Mrs. Tittlemouse’s bedroom, where she slept in a little box bed.

For more Gorey-meets-Addams, try the video game Creaks.

Yes! So want the Beast’s library! Any book that mentions a library with not a lot of detail, that is the library I picture.

I want the Beast’s library attached to a hobbit smial that has ceilings high enough for me and a garden full of fragrant roses of different kinds.

I also want to be able to go to the current iteration of Callahan’s and back with a snap of my fingers. Knowing that everybody there is committed to being okay to be around, available to help in times of crisis, but willing to ignore you if that’s what you want? For that I could abide the smell of booze.

Yes, the All-of-a-Kind family! I remember the bedroom where four of the sisters paired up in beds, while the fifth, Henny, had her own bed where she dreamed up mischief.

Growing up, I remember reading about the Underground Railroad and desperately wishing our house had been a station with a secret passageway despite the fact it was not nearly old enough. Now, in addition to secret rooms, I’d also like a library/adult-sized jungle gym, kind of like the Beast’s library but cozier, with suspended walkways and tunnels and platforms at different levels with shelves built into all the walls and reading chairs (armchairs, hammocks, etc.) scattered throughout. And a Lothlorien treehouse. And then fill it with cats and poor college students who can live rent-free if they take turns cooking dinner and don’t throw too wild parties.

Now I’m sad I’ll probably never be rich enough to actually build this.

I have that version of ‘The Wind in the Willows’ and it is one of my most treasured books.

Molly… thank you for this. Your mention of Wind in the Willows (reading about Badger’s place whilst lying under the dining room table while a storm raged outside) and “messing about in boats” brought to mind how desperately I, as a child, wanted to live on the “Rodent”, the boat built by Amos the mouse in Amos and Boris. A boat as a home, a cozy cabin en route to adventure after adventure was (and quite honestly still is) endlessly appealing to me.

Growing up I wanted adventure. I wanted to live in Camelot, Minas Tirith, or the Starship Enterprise. I was a small-town kid who knew there was something bigger out there. Now, many years later and retired, I absolutely know what Frodo meant when he said he once wished a dragon would shake things up in his home town, but now, even if he could never go back to it, just knowing it was there and was safe is enough. The perfect place for me now would be Bag End, a comfy home with a good larder where there’s never danger of being late for tea. Hobbits understood hygge before it was a thing.

The Tardis always struck me as the ultimate cubbyhole.

My magical dream home was always James Gurney’s Dinotopia. The tree houses, the waterfall city, and of course, dinosaurs, dinosaurs, dinosaurs. Everyone happy and comfortable and colourful and hanging out with DINOSAURS.

I loved Badger’s house in Wind in the Willows, and also Milly Molly Mandy’s attic bedroom – and the house made of living willow in Enid Blyton’s The Secret Island.

More recently I adored the starship in Becky Chambers’ Long Way to a Small Angry Planet

John Crowley’s Little, Big serves not one, but two dream houses: Edgewood, a labyrinth that leads to Faerie, powered by a magic orrery, and Mouse’s crumbling but equally dreamy dwelling in the City.

As a bonus, we get a book within a book, about –what else– houses!

The first thing that came to mind for me was Redwall. The ultimate fictional idea of home for me, I think. Food and stories and good friends (plus plenty of room to explore, including gardens!).

I always wanted a Secret Garden. :)

I always longed for Rivendell, especially after Jackson’s FotR came out.

But the fictional “home of my heart” has always been Evenmere, the centerpiece of the novel The High House by James Stoddard. A mansion containing countries, a dragon in the attic, a library with portals to other realms–I re-read this book every couple of years and it never gets old.

Kyna @12: Growing up, I remember reading about the Underground Railroad and desperately wishing our house had been a station with a secret passageway despite the fact it was not nearly old enough.

Ha! I grew up in an old farmhouse with multiple buildings on the property that really was supposedly a station, but I sought for a secret room/passageway over and over again without any success. I was sure there must be one, in spite of the fact that these stations often did not have such a well-designed hiding place.

Meanwhile, back to the topic, I don’t think I have a favorite, although I’ve often wished that Frodo and friends had had an opportunity to spend longer in the house in Crickhollow. I wanted to hear more about that area and the house itself.

The Burrow, The Weasley family’s home in the Harry Potter series is a favorite.

I think the house in Clifford Simak’s “waystation” would be cool for awhile. Aliens arriving from space occasionally and as long as you are inside it you don’t age.

I used to feel this way about the depiction of 221B Baker St in the Sherlock Holmes production that stars Jeremy Brett .

Why would you worry about breaking things in Toad Hall? Mr. Toad certainly didn’t