Do you read science fiction? Do you care if people call it sci-fi or SF? Do you like hopepunk? What about cli-fi? Do we need that one or is climate a subset of science, bookishly speaking? Is it steampunk’s fault we started mashing words together and calling them genres?

What’s in a name, anyway? What’s a genre? Is it different from a category? What about a label? What about themes and topics and tropes and character types and narrative types and styles?

Why am I asking so many questions? Because people are trying to make “microgenres” a thing, and I have extremely mixed feelings about it.

The first time I saw the word “grimdark,” I thought it was a joke. Not in a snotty, snobby way, but truly, I thought it was someone making a joke about the kind of fantasy where everything is terrible and everyone dies. It took me a long minute to realize that, like steampunk, it was two words stuck together to describe something specific. Not just dark! Not just grim! Both. (It probably says something about my reading habits that this word was already well in use before I encountered it.)

The first time I ran into a genre term at which I looked very askance, it was cli-fi. There are various reasons for this (some of which Jeff VanderMeer touches on in his Esquire piece about climate fiction), but the primary one was that it felt unnecessary. Climate study is scientific. Ergo, it’s science fiction. I didn’t want an extra label.

And yet at this point, there’s enough climate fiction—and it’s been written for years and years and years—that it kind of warrants its own classification. In “Genre: A Word Only a Frenchman Could Love,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, “A genre is a genre by virtue of having a field and focus of its own, its appropriate and particular tools and rules and techniques for handling the material, its traditions, and its experienced, appreciative readers.”

Le Guin is saying this in contrast to an imagined (but not imaginary; this keeps happening) writer setting out to reinvent science fiction, having no idea that their brand-new ideas are nothing of the sort. But it also gets at what makes me resistant to an increasing array of petite or micro-genres: the lack of depth to the field; the lack of history. I want a genre to be a big bucket, a pool in which all kinds of books swim. I don’t need an individual genre for every kind of book I like. Do I love books about women figuring their shit out? Yes. Is that a genre? Lord, no.

This is not to say that there isn’t value and purpose to categorizing books in all kinds of ways. But grouping books by theme or setting or plot points doesn’t make them a genre. It makes them a group. A category, if you will. An idea for a list post. Maybe even a tag, if you’re thinking along certain fandom lines (hello, Tumblr, I love your tags, the more over-the-top, the better).

Over the years I have seen many (too many) discussions about young adult fiction that boil down to: “Is it a genre or is it a marketing category?” It’s emphatically not a genre, to my mind. It encompasses every genre: realistic fiction, mystery, fantasy, you name it. It’s a term that describes books that are written and published with a certain audience in mind, like chapter books, or middle grade books, or even adult fiction. Those are catch-all categories, full of genres. The argument was fundamentally broken, I think, by including the word “marketing.” Did YA grow as publishers figured out how to better market it, as younger people became target markets online, as certain series blew up and made it seem more profitable? Now that’s a question about marketing. But the section is just a category.

My point here is, in part, that maybe we’re afraid of saying “category” because it sounds technical or boring. But categories can be good, actually! And so are themes and types and styles and all the other things we can group stories by that are not genres. What is dark academia if not a vibe? What is first contact if not an event? What is a generation ship if not a terrible idea that leads to all kinds of disaster almost without fail?

(I love generation ship stories, I really do, but I have rarely been as stressed out as I was reading Marissa Levien’s The World Gives Way.)

But am I being fair? Am I resistant to the idea of a microgenre because, as Book Riot notes, “The use of these microgenres, along with other tidbits of information such as categories and tags, feeds algorithms and helps make books discoverable”? Books being discoverable is good. Using microgenres in order to feed algorithms makes me want to break the internet.

Merriam-Webster defines “genre” as “a category of artistic, musical, or literary composition characterized by a particular style, form, or content.” It says nothing about how big or small the category is.

Part of why I want genres to be big buckets may be because I want us to regularly acknowledge that literary fiction is a genre. It’s not some kind of neutral, a genre-free space while everything else gets shunted off into other boxes. There is no un-genre, because genre isn’t a dirty word, no matter how many times people try to use it to indicate all fiction that isn’t so-called literary. The Le Guin piece I quoted earlier was in part about how “the word genre began to imply something less, something inferior, and came to be commonly misused, not as a description, but as a negative value judgment. Most people now understand ‘genre’ to be an inferior form of fiction, defined by a label, while realistic fictions are simply called novels or literature.”

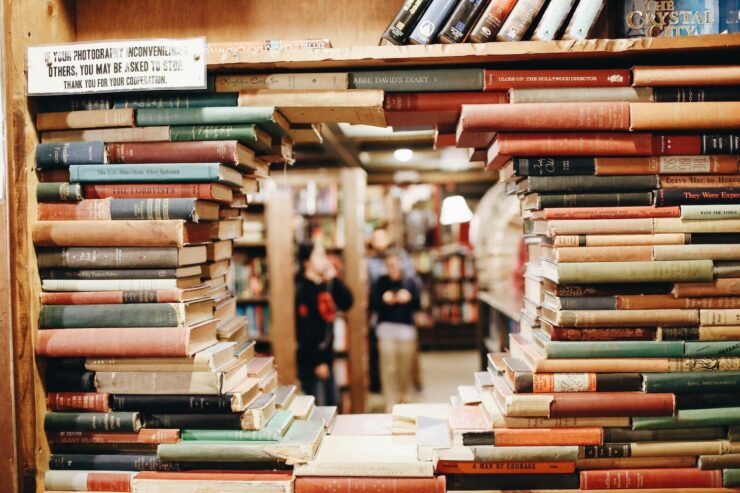

Buy the Book

The Water Outlaws

Haven’t you heard someone sneer, “I don’t read genre fiction”? They don’t mean a specific genre; they mean anything outside the fiction section of the bookstore. The fiction section which, by virtue of how it is chosen and arranged, also exists as a genre.

The lines blur, as we all know. Literary fiction publishers release books full of magic and mystery, and sometimes—though seemingly less often—SFF publishers release books that lean a bit more toward a middle ground. I am not here to argue about what makes a book SFF or not, because the reasoning is sometimes very simple (it depends who published it) and sometimes very arcane, and sometimes nothing more than personal feelings. Vibes, again. So many vibes.

I am here to ask: Does turning everything into a genre help? Is a microgenre different from a subgenre? I somehow have no issue with subgenres—urban fantasy, alternate history, space opera—but if you were to tell me I ought to classify The Book Eaters and The Book of Night as, say, “small-town evil patriarchy” books, I would refuse, possibly impolitely. Would I describe them both as books that deal with evil patriarchy in small(er) towns? Sure. But that doesn’t create a genre.

What I’m resistant to about the idea of microgenres is, in the end, that it feels like hurriedly inventing labels rather than letting things grow into their own shapes. That’s why cli-fi felt so forced, back in the ’90s when it started turning up. Someone really wanted to make cli-fi happen, and it eventually did, but not because they wanted it to. It happened because the books happened (and because climate change happened, continues to happen, will continue to happen until the powerful realize that it is also happening to them). A certain massive retailer may make a lot of mini-genres for it to rank books with; does that mean we want to borrow its language?

Is a microgenre a too-small box or a useful tool?