Welcome to Close Reads! Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, Paul Morton sets sail for one of Herman Melville’s early nautical adventures, Redburn, and the highly specific, very queer-coded cover Edward Gorey contributed.

At the beginning of his career, from 1953 to 1960, Edward Gorey drew book covers for Anchor, cheap paperbacks of quality literature, available to college students and laypeople. Gorey would go on to become a Great American Weirdo, the illustrator of dozens of books, though I still know him best for the PBS series Mystery!, for which he designed the opening titles. He refined his style and sensibility through the years, but he defined both early on: spare, carefully chosen lines against even sparer backgrounds; a wicked, Edwardian humor. NYRB has reissued some of this work. On Gorey’s cover of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, the Martians are both menacing and awkward, comical bumblers as well as mass murderers.

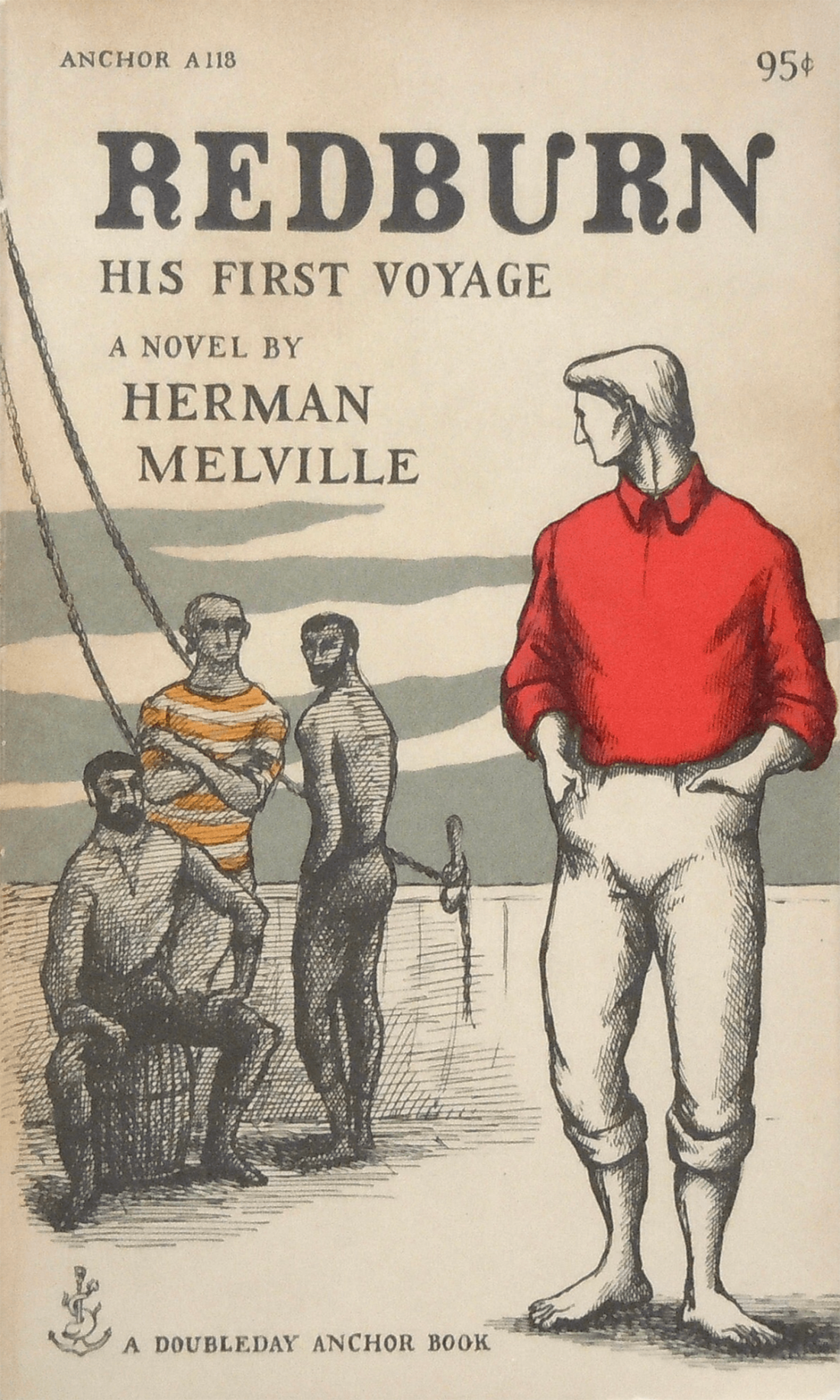

I first learned about these editions some years back, at a bookstore in Vancouver, which kept a full shelf dedicated to the Gorey Anchors. For five Canadian dollars, I bought a 1957 copy of Herman Melville’s Redburn, a novel first published in 1849, which was based on the author’s first voyage out to sea, from New York to Liverpool, one he undertook in 1837 at the age of 18. I was unlikely to ever display the book in my small, cluttered apartment, and I didn’t see myself reading it anytime soon, but the cover intrigued me enough to buy it: a sexual neophyte, the excitement in his crotch suggested in cross-hatching, glancing both curiously and longingly at three older, rougher men, who regard the boy with a combination of lust and contempt. It was a relic from a dark time when any hint of homosexuality was still transgressive.

Gorey had read many if not most of the books he was assigned to illustrate, but his covers were never literal. Instead, as Steven Heller writes in his introduction to Edward Gorey: His Book Cover Art and Design, his drawings “evoked moods or set off sparks of recognition.” I eventually read Redburn, one night when I was eager for a taste of weird America, and no, the cover does not represent any one scene in the book.

Redburn is, at heart, a thrilling work of reportage. Wellingborough Redburn, the eponymous hero based on young Melville, has more than an intellectual interest in some of his fellow sailors, but the book is mainly interested in the economies of transportation and transcontinental trade in the mid-19th century, how laborers, passengers, consumers, and owners negotiate a system that is beyond any one person’s control. The prose is precise and fine, descriptive and thorough. It is not the baroque or apocalyptic Melville of Moby-Dick or the Civil War poems, nor the proto-modernist Melville of “Bartleby, the Scrivener” or The Confidence-Man. This is Melville as John McPhee.

Still, Gorey might have been thinking of one chapter in the book, 10 of the novel’s 300 pages, the one thirtieth of the book every Melville scholar writes about. Redburn, having disembarked in Liverpool, meets a young man named Harry Bolton, and although Bolton does not appear on Gorey’s cover, his subjects, at some point in their lives, probably took his like for an amour.

He was one of those small, but perfectly formed beings, with curling hair, and silken muscles, who seem to have been born in cocoons. His complexion was a mantling brunette, feminine as a girl’s; his feet were small; his hands were white; and his eyes were large, black, and womanly; and, poetry aside, his voice was as the sound of a harp.

Bolton’s appearance disrupts the narrative entirely and transforms Melville’s prose, turns what has been a controlled study of a capitalist machine afloat on the water into a mystical dream journey to the underground of London. Imagine if Ken Burns made a ten-part series about the shipping industry, hit a crisis of confidence on episode seven, and decided to remake Fellini Satyricon.

Bolton leads Redburn into a “semi-public place of opulent entertainment,” and in describing it, Melville anticipates the Symbolism of the late 19th century. “From sculptured stalactites of vine-boughs, here and there pendent hung galaxies of gas lights, whose vivid glare was softened by pale, cream-colored, porcelain spheres, shedding over the place a serene, silver flood.” Redburn, a solid reporter but a true naif, sees the well-dressed gentlemen, fine waiters, and a “handsome florid old man,” called the Duke, and assumes he is among a noble set. The establishment, Bolton tells him, is known as “Aladdin’s Palace.”

Bolton directs Redburn to remain alone in a room for the night, throughout which he is haunted by mysterious sounds in the distance, “hushed ivory rattling from the closed apartment adjoining.” He suspects he has been drugged, and his nightmare visions are unmistakably phallic: “All the mirrors and marbles around me seemed crawling over with lizards; and I thought to myself, that though gilded and golden, the serpent of vice is a serpent still.”

When Bolton reappears, Redburn asks if he was off gambling. Harry laughs and replies enigmatically. Gambling?—“what two devilish, stiletto-sounding syllables they are!” The once confident and deliberate young man is now manic and he asks Redburn to hold onto a dirk, telling him he has thoughts of suicide.

What happened that night is unclear. Was Bolton servicing a gentleman? Was Bolton attempting to pimp out Redburn? Was Redburn himself violated? Melville doesn’t answer those questions. The boy returns to Liverpool, boards the ship and heads back to New York.

It will not surprise you to learn that prominent scholars, as late as the mid-aughts, have resisted a queer reading. For one, the décor is common to heterosexual brothels of the period. And although it was highly possible that Melville, like most whalers, enjoyed homoerotic adventures during his long journeys on exclusively male ships, it is not so obvious that he sought out similar encounters on land. Moreover, the Aladdin’s Palace sequence is probably based on another’s experience, as it is unlikely that Melville himself ventured beyond Liverpool. Still, there is ample evidence that Melville developed strong romantic feelings towards his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, and his career, all the way up to his very last novel, betrays a profound appreciation for the beauty of the male body. Such critics do the same work of Bolton himself, refusing to name what cries out to be named.

Like Melville, Gorey evokes a homoerotic aura. But he does not depict the decadent pseudo-upper-class world of Aladdin’s Palace, as much as the cruising culture from the period when he was working, a culture that collapsed the class structure of Eisenhower-era America. A curious middle-class teenage boy may have recognized himself on this cover, and he may have bought the book for 95 cents. He might keep a picture of James Dean in his bedroom. He might collect body-building magazines. He might have an immaculate Eagle Scout uniform in his closet. And he might very well spend nights by the railroad tracks or in a particular corner of the town park. Does he ever actually read Redburn? If so, the book may give him a taste for camp. And it may help him question the mores of the economic class just above his own.

I don’t know if such teenagers still exist, avid readers hungry for the transgressive in capital-l Literature. No matter how often I move, I have no plans of ever dropping my Redburn. I hold onto it in memory of whoever among Melville’s few readers in 1849 felt a stirring of excitement when he read those ten pages, and of that teenage boy in 1957, who by the 1970s was organizing chic literary salons in SoHo. It is the glorious task of every generation to reinvent sex for themselves, hopefully for the better.

Sometimes the sub-text is not too sub, as in one scene from Moby Dick, where the sailors are processing the whale oil, squeezing out lumps in the fat by hand, and getting more and more interested in squeezing each other’s hands in the oil. Would love to see the Edward Gorey illustration for that scene.

I’d say that cover is less subtext and more Goodyear-blimp-painted-flesh-tone-with-two-massive-sagging-flesh-toned-spherical-sacks-dangling-below-the-rear-fins-with-“GAY”-flashing-on-the-side-message-board overtext.

Pretty amazing for its time but from my earliest exposure to Melville in junior high I sensed the homoeroticism saturating so much of his work that I wonder if Gorey wasn’t reflecting a vibe everyone else felt.