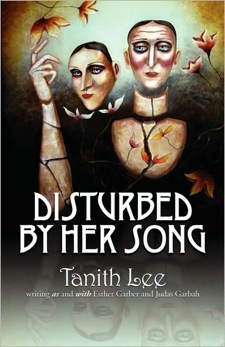

The conceit behind Tanith Lee’s newest collection, Disturbed by Her Song, is a sort of super-textual connection with the characters who Lee is writing as, whose names share her byline: Esther Garber and Judas Garbah. There are stories about the siblings, by them, and stories that they tell to the reader, also. It’s a tangled universe in a thoroughly interesting way. Both Esther and Judas tell stories of queer love and sexuality, as they are both of the particular persuasion, but from very different “angles,” one might say. Judas’s stories tend to be much sadder and stranger.

I must admit the narrative games work well; the voices of the two narrators are sharply distinct from each other and the introduction Lee gives us makes the stories themselves more strange, with a touch of ghostliness and surrealism. It begins the book by taking the reader out of the mindset they’re used to—made-up narrators with an author pulling their strings—and tells the reader, no, this is something different, this is not the same.

As the table of contents will show you, some stories are by Esther, some by Judas, and some by both Tanith and Esther. She addresses the differences in the stories where she is, so to speak, “in conversation” with Esther and the things that are revealed in them that wouldn’t be otherwise. (There’s also another sibling, Anna, who has no stories in the collection but who is mentioned.)

Where another author might make this seem like a gimmick or flat-out crazy, Lee pulls it off with a charm and skill that matches her previous work. As one may have gathered from previous reviews in the Queering SFF series, I have a ridiculous weakness for narrative flair and nuance, writers who play with the very concept of story and narrator. (I love the straightforward things, too, and they are often the very best, but still. I nerd out over creative twisting of the medium.) This book totally, completely satisfies that nerd-urge.

I’m not quite sure what genre I would classify it under, beyond “queer fiction.” The first word that comes to mind is actually “surrealist” in the artistic sense instead of any commonly accepted fiction genre. The imagery that threads through each story is dreamy, weird and often slightly off-balance from the real in a way that can only be described as surreal. So, there it is: perhaps Disturbed by Her Song isn’t speculative fiction, necessarily, as a whole. It has speculative stories, but considered all as one, I’d say it’s queer surreal fiction.

Surreal or speculative or both, the stories are fairly good. The first, “Black Eyed Susan,” is one of my favorites of the collection. It has an almost topsy-turvy dream air to it—a strange hotel in the winter, full of strange guests and stranger employees, where Esther had stumbled into something that may or may not be a ghost story, depending on how the reader chooses to analyze the ending. The uncertainty, the possibility of the supernatural without explicitly proving it, is one of the key themes of this collection. In every story that holds a speculative sway, there are hints and sideways images of the supernatural, but it’s not always clear whether or not the reader—or, the narrators, really—are imagining things. “Ne Que von Desir” for example never says a word about werewolves. It just gives the reader Judas’s memories of the event and the man he encountered, full of wolf imagery and weird occurrences. (This tale also appears in Wilde Stories 2010, reviewed previously.)

Not all of the stories are speculative, though—most are more traditional literary tales (as traditional as queer, erotic fiction can be), about love and humans and miscommunication. There are frequent undercurrents of race and class that weave in an out of several of the stories, often eroticized, in the form of power that one characters holds or may hold over another. It’s a very socially conscious book but manages not to be pedantic despite that—it seems to paint pictures of the world around it, sometimes in uglier colors.

As for the stories that did less for me, “The Kiss” was the least enjoyable of the lot. It’s not a bad story; the writing is precise, but it’s very much a “told story” instead of an immediate narrative. There’s a lack of emotional connection to the lead girl and the moment of tension that lends the story its discomfort (the rapacious male crowd, incited to violence) defuses so quickly and easily that it gives the reader barely a moment to feel fear or unease. I disliked the last line, also; it seemed a bit trite to add on the speech, “I lied.” The final image—of the girl returning to her apartment, where there is no father and never was, and kissing the lipstick print—is much more effective on its own, without the final line. If that seems nitpicky, it’s only because the language and sentence structure in the rest of the book is so very precise that it seems jarring to have that particular misstep at the end of a story.

Overall, especially to fans of Lee, I would recommend this collection. For the fans of surreal, dreamy literature that still manages to have precise and evocative imagery, too. The stories have a touch of the erotic without leaning to erotica, but they also have overtones of isolation, despair, and the pressure of an unforgiving and unwelcoming society—themes prescient to many a queer reader. I give Disturbed by Her Song an A- as a whole: good work, reliably gorgeous, and with only one story I really didn’t care for. (One caveat: perhaps a little difficult to engage with for someone who isn’t interested in poetics or surreal narratives. It’s much more a “literary collection” than a speculative one.)

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.

I’ve heard Tanith Lee’s name floating around but I’m not sure where to begin in reading her work. Any recommendations?

@welovetea: For the novels, try the Flat Earth series, which is currently being reprinted. For short stories, there’s a two-volume release of selected stories, TEMPTING THE GODS and HUNTING THE SHADOWS.

@welovetea @Craig Laurance Gidney

That would probably by my recommendation, too. Or, “The Secret Books of Paradys.”