I’m admittedly a bit of a soundtrack nerd; in so many cases, the right music can make or break a scene, while the wrong music can ruin the vibe faster than you can say “Ladyhawke/WangChung/GoNinjaGoNinjaGoooo.” (Though you should never actually say that, as it summons unspeakable evil).

Since we’re tackling so many Bowie albums and movies this week, I thought it might be fun to take a look how his music has been used in film and television over the years. It’s interesting to see how a scene can completely recontextualize a particular song, and the heightened emotional impact that music can bring to a moment (or even an entire series, in some cases), and so I’ve rounded up a few of my favorite examples of Bowie’s contributions to both big and small screen soundtracks. And just to make it interesting, I’m not focusing on original, made-to-order compositions, but tracks that existed independently and had a life of their own before Hollywood (or the Beeb) came calling.

It’s difficult to find a better example of the perfect pairing of song and sweeping cinematic sequence than Quentin Tarantino’s inspired usage of “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” in 2009’s Inglourious Basterds. The consummate film geek, Tarantino has built a career out of making movies which constantly refer back to earlier movies, from French New Wave art house films to kung fu and Blaxploitation cult classics, but Inglourious Basterds takes this hyper-referential style even further. It’s a movie about the complicated relationship between cinema, propaganda, historical reality and perceived truth—a war movie that’s actually a commentary on war movies, in which film itself is (literally) used as a weapon of mass destruction, as well as mass distraction.

The scene in question begins with Bowie’s slow, brooding introduction, as the camera follows theater owner Shosanna preparing to greet Hitler, Goebbels, and other Nazi officials for the premiere of a Nazi propaganda film. The vocals and music build into a dramatic crescendo as she sits in front of a mirror, a glamorous woman applying her makeup as if it were warpaint. The gothic artificiality of the scene (the anachronistic music, the movie theater setting, the ritualistic pacing of her movements) purposefully draws attention to the layers of performance at work—actress Mélanie Laurent playing the role of Shosanna Dreyfus, a Jewish woman forced to adopt a fake identity under the name Emmanuelle Mimieux, pretending to be a Nazi sympathizer, her glamorous façade masking the guerilla filmmaker who intends to burn down the theater, killing everyone inside.

The scene in question begins with Bowie’s slow, brooding introduction, as the camera follows theater owner Shosanna preparing to greet Hitler, Goebbels, and other Nazi officials for the premiere of a Nazi propaganda film. The vocals and music build into a dramatic crescendo as she sits in front of a mirror, a glamorous woman applying her makeup as if it were warpaint. The gothic artificiality of the scene (the anachronistic music, the movie theater setting, the ritualistic pacing of her movements) purposefully draws attention to the layers of performance at work—actress Mélanie Laurent playing the role of Shosanna Dreyfus, a Jewish woman forced to adopt a fake identity under the name Emmanuelle Mimieux, pretending to be a Nazi sympathizer, her glamorous façade masking the guerilla filmmaker who intends to burn down the theater, killing everyone inside.

The song itself clearly works in terms of mood as well as lyrically, handily setting the scene for the coming conflagration, but it also contributes to this sense of enforced artificiality and cinematic distance, especially when one considers that it was originally written as the theme to 1982’s Cat People, which was itself a remake of Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur’s 1942 cult classic. Both versions are preoccupied with the dangers of female sexuality, the beautiful woman as predator, unable to control her desire or identity who must either be killed or live as a caged animal. In recycling this song at such a pivotal moment in the film, Tarantino draws on this history, complicating these thematic elements and making them part of the scene—Shosanna might be predatory, but she’s hardly a victim of her own irrational desires.

Instead, she’s an auteur, an artist, pretending to play a role while secretly controlling the script, and without giving too much away, her vision ultimately prevails. Unfortunately, finding a decent video of the scene online is difficult; you can check out this one, but beware of major spoilers after the 2:40 mark; as a compromise, here’s “Cat People” played over the image of Laurent in formal assassination attire, ready to take out some Nazis:

Of course, Tarantino is just one of many directors who have mined the Bowie songbook over the years and hit gold in all kinds of different genres: John Hughes used “Young Americans” in Sixteen Candles, but more importantly, he lifted a verse from “Changes” and used it as the epigraph to The Breakfast Club, thereby enshrining David Bowie forever in the hearts of angsty suburban teens for generations to come. Bowie tunes serve as musical set pieces in both A Knight’s Tale, an action-adventure film (albeit an unconventional one) and wacky, postmodern jukebox musical Moulin Rouge. A slightly modified cover version of “I Have Never Been to Oxford Town” is used to good effect in Starship Troopers (Bowie, a Heinlein fan who once talked about making a film version of Stranger in a Strange Land, must have been pleased).

Then there are the indie directors, from Lars von Trier (who has mentioned being “fascinated” by Bowie in interviews, and used Bowie tracks in both Breaking the Waves and Dogville) to David Lynch, who actually cast Bowie in a typically bizarre role in Fire Walk with Me, as well as using two different versions of the Bowie/Eno collaboration “I’m Deranged” to score the opening and closing scenes of Lost Highway. The song wasn’t written for the movie, predating it by a couple years, but it may as well have been, with its disturbing intensity and sense of heavy melodrama.

On a much lighter and inexpressibly twee-er note, director Wes Anderson based the entire soundtrack to 2004’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou around late-60s and 70s-era Bowie songs. The acoustic, Portuguese cover versions of many of the songs by Brazilian performer (and Life Aquatic cast member) Seu Jorge lend a softer, stripped-down beauty to Bowie’s rock and roll originals, and imbue the film with a mellow, dreamlike quality throughout. As much as I enjoy the covers, though, the shining moment of the film might be Bill Murray’s jubilant end-credit strut over Bowie’s version of “Queen Bitch,” as his crew gathers around him in a clever nod to the iconic ending of Buckaroo Bonzai:

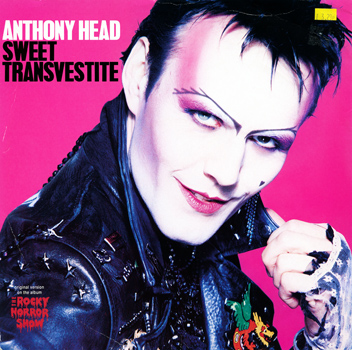

Moving on to television, I have to admit that I was convinced, before doing any research, that there were a bunch of Bowie songs featured on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, although it turns out that’s not the case. It’s such a music-centric show, and you just know Giles is a huge glam fan, but as far as I can tell, only one Bowie song ever made in on to the show’s soundtrack, and it’s the relatively obscure “Memory of a Free Festival” off of Space Oddity, which failed miserably as a single when it was originally released in 1970.

It’s a great choice, however, for the scene in “The Freshman” in which Buffy barges in on the beginning of Giles’ rapidly developing mid-life crisis. The first episode of Season 4, “The Freshman” finds Buffy struggling to adapt to college life, while Giles tries his hand at being “a gentleman of leisure,” although it’s clear that neither of them are really ready to move on without the other. The built-in nostalgia of the song and the fact that it’s not a more obvious choice both work in terms of the scene in a way that a more recognizable hit song probably wouldn’t have; as is, it’s quite a nice touch. And for what it’s worth, Joss Whedon would eventually score a few more fanboy points by including a supervillain named “Dead Bowie” in Doctor Horrible‘s Evil League of Evil

It’s a great choice, however, for the scene in “The Freshman” in which Buffy barges in on the beginning of Giles’ rapidly developing mid-life crisis. The first episode of Season 4, “The Freshman” finds Buffy struggling to adapt to college life, while Giles tries his hand at being “a gentleman of leisure,” although it’s clear that neither of them are really ready to move on without the other. The built-in nostalgia of the song and the fact that it’s not a more obvious choice both work in terms of the scene in a way that a more recognizable hit song probably wouldn’t have; as is, it’s quite a nice touch. And for what it’s worth, Joss Whedon would eventually score a few more fanboy points by including a supervillain named “Dead Bowie” in Doctor Horrible‘s Evil League of Evil

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Doctor Who and Torchwood have both made use of the song “Starman,” although my favorite subtle, Bowie-related Who moment comes from the Hugo Award-winning 2010 episode “The Waters of Mars,” in which the Doctor finds himself at the first human colony on the Red Planet: Bowie Base One. Well played, RTD…well played.

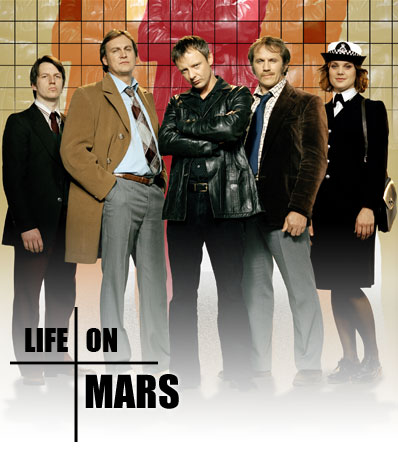

Which brings us, inevitably, to the BBC masterpiece Life on Mars. Beyond borrowing the song for its title, the original series (the one starring The Master John Simm, not the American remake) begins when our protagonist, police officer Sam Tyler, is struck by a car while “Life on Mars” plays on his iPod

only to wake up to the same song playing on an 8-track 33 years in the past, having been thrust back into the 1970s Manchester he grew up in. Or so he believes

the show  continuously plays with the possibility that Sam may actually be insane, or in a coma, and that the 1973 “reality” is an imaginary construct—scenarios which make the use of the Bowie tune all the more brilliant.

continuously plays with the possibility that Sam may actually be insane, or in a coma, and that the 1973 “reality” is an imaginary construct—scenarios which make the use of the Bowie tune all the more brilliant.

The song captures the inherent strangeness of his situation, the troubling disconnect he feels with the people around him, the idea of having lived through these times before, as a child, even the image of “the lawman beating up the wrong guy” fits perfectly—and maybe a little too perfectly. How much do we read into the fact that the song was the last thing he heard before being crushed by a speeding car? Are all the Bowie and glam rock references simply a naturally occurring element of 70s British culture, or do they indicate a reality cobbled together out of memory, Sam’s past experiences filtered through music, movies, and the TV cop shows he grew up on?

The tension, and the not-knowing, fuels the series as much as Sam’s attempts to find his way back to 2006, and music plays an integral part throughout. Not only does “Life on Mars” feature prominently in the first episode and again in the climactic moments of the finale, but the series regularly employs other Bowie songs as well as other glam rock staples from bands like T. Rex, Roxy Music, Mott the Hoople, Sweet, and Slade. The show also has fun with Sam’s obvious delight at being a fan thrown back into glam’s glittery Golden Age. In one of my all-time favorite scenes, he finds himself face to face with Marc Bolan, and the resulting conversation is sweet and sad and funny all at once, as Sam warns his hero to “drive carefully” (Bolan tragically died in a car crash in 1977, at the age of 29):

Meanwhile, the song playing in the background? “The Jean Genie” which also happens to be the self-appointed nickname of Sam’s hard-drinking maverick superior, DCI Gene Hunt. Coincidence? Not bloody likely.

Life on Mars took the concept of Bowie-as-soundtrack to a whole new, amazing level by integrating his music into the fabric of the series itself—a practice which continued in its sequel series, Ashes to Ashes. It’s a stellar example of how music can be used to deepen and create meaning and dramatic tension onscreen, and we can only hope that Bowie’s iconic status and incredible range as a musician and songwriter will continue to inspire such memorable and innovative material, as long as writers and directors endeavor to combine his distinctive sound with their vision.

Bridget McGovern knows when to go out. And she knows when to stay in. Gets things done.