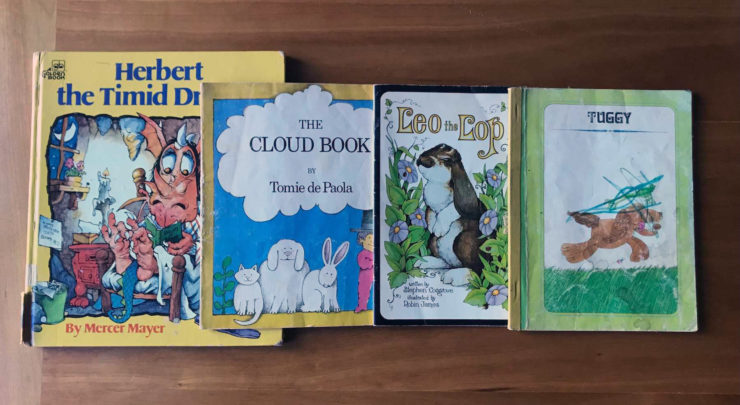

The book I’ve owned the longest has zero cachet, zero cool, zero name recognition. It is not an old copy of my beloved The Castle of Llyr, or a well-worn copy of Mercer Meyer’s Herbert the Timid Dragon. It is an early reader called Tuggy, unexpectedly stamped “Bailey Hill High School” on the inside cover, in between scrawls of crayon.

Tuggy is a book meant to teach a very young reader words. I would not remember that it was part of my learning-to-read process, except that I still have it, tattered and ink-stained, on a shelf with other ancient, ragged children’s books, including Leo the Lop and Tomie dePaola’s The Cloud Book, thanks to which I once knew the names of a lot more clouds than I do now.

There’s no real reason for me to have these books. They don’t say much about me, other than that—like so many kids—I like stories about animals and the world around me. They’re bedraggled copies, not the kind of thing a person collects. I don’t have kids to pass them on to. You could say they’re sentimental, unnecessary, even clutter.

But they mean something to me. They’re part of my story. And isn’t that, when you boil it down, why we keep anything—most of all books?

I’ve been thinking about personal libraries because someone in a high-profile paper recently wrote a piece against them. To a bookish person, this seems so baffling a position as to be an outright troll, and at first I was resentful that I took the bait. But then I sat and looked at the wall of books in my house—there are several of these, to be honest, but one is the main wall, all the books my partner or I have actually read—and thought about what’s on that shelf, what isn’t, and how anything got there at all.

My first library was a single shelf of books on a board held up by cinderblocks—books I had been given as a child; books I had purloined from my parents’ shelves and made my own; books I will never know the provenance of. I was so enamored of libraries that I put little pieces of masking tape on the spine of each, each labeled with a letter and number, just like in the real library. This was poorly thought out, as any new addition to the library would not fit in the numbering system, but I was in elementary school. Foresight was not my strong point.

When I was young, I kept every book, even the watered-down wannabe Tolkien fantasies I didn’t like that much. Since then, I’ve moved numerous times; spent four years in dorm rooms with nowhere to store more books than strictly necessary; lived briefly overseas and made difficult choices about which books would come home with me; stored books on the floor, in milk crates, in apple crates, in bookshelves passed along from neighbors or handed down from relatives; in Ikea shelves of every shape and size; and, in one case, in a petite wooden bookcase that I do not remember getting. It’s the perfect size for my craft books, fairy tale books, references and folklore. It’s the one place I shelve read and unread books side by side, a collection of inspiration, aspiration, and ideas that I reorganize every so often.

I don’t keep everything anymore. The first time I got rid of books, I was a college kid with my first bookstore job, and I was disappointed in a much-hyped Nicholson Baker book that did absolutely nothing, so far as I could tell. I didn’t want it. This was a wild new feeling, wanting to be rid of a book—so wild, at the time, that I remember it all these years later.

I don’t remember what I did with it, but I no longer have the book.

What goes makes up your story as much as what stays. Sometimes, when I look at my shelves, all I see are the books I didn’t keep: the first edition of The Solitaire Mystery that I never got around to reading, and so let go; the second and third books in series that I liked well enough but was never going to reread; books I worked on, in various publishing jobs, but just never had a copy of. They’re ghost books, hovering around the edges of the shelves, whispering into the pages of the books I did keep.

I started keeping reading lists as a way to keep track of all the books I read but didn’t keep, but they don’t offer the same sensation as actually looking at the books: being able to pull them off the wall, page through them, remember what it was that drew me to them or made them stick in my memory. Some old paperbacks have the month and year I finished them penciled in the back. A very few have gift inscriptions; some are signed, mostly from events I once hosted. There is one book that’s moved with me for twenty years that I absolutely hate. I loathe this book. It is about indie rock bands in the ’90s, and not a single word of it rings true. But I keep it because I read it and hated it, and my musician friends read it and hated it, and the memory of all hating it together is a weird joy that I think of every time I see its stupid cover on my shelf.

What you get from a book stays in your head, but it isn’t always immediately accessible. I’m terrible at remembering plots, but paging through chapters brings things back. I remember feelings, weird flashes of imagery, characters I loved or wanted to kick. My books are a practical resource—I look at them when I’m writing, when I’m trying to recommend a book to a friend, when I’m thinking about what kind of book I want to read next—but they’re also a story. They’re a story about reading Perfume in college, and loving it so much I won’t give up my cheap paperback even though my partner’s beautiful hardcover sits right next to it. They’re a story about loving someone who adores an author I’ve barely read; dozens of books I don’t know anything about share shelf space with my favorites, with the books that helped make me who I am.

Buy the Book

A Marvellous Light

The library is a story about how much I love my books: enough that I’ve been willing to move hundreds of them across the country multiple times. They’re a story about how I categorize them: unread in one space, YA in another, all the mass markets stacked on the topmost shelf, lightweight and easy to get down. (I kind of envy friends whose libraries exist in a state of chaos that is rational only to them.) The books are a story about what I used to read and what I read now, about the few books I’ve been carting around since college (Jose Donoso’s The Garden Next Door, which every year I intend to reread) and the ones I read the minute I got them (Becky Chambers’ A Psalm for the Wild-Built) and the ones I absolutely had to have my own copy of after getting them from the library (Nalo Hopkinson’s Midnight Robber).

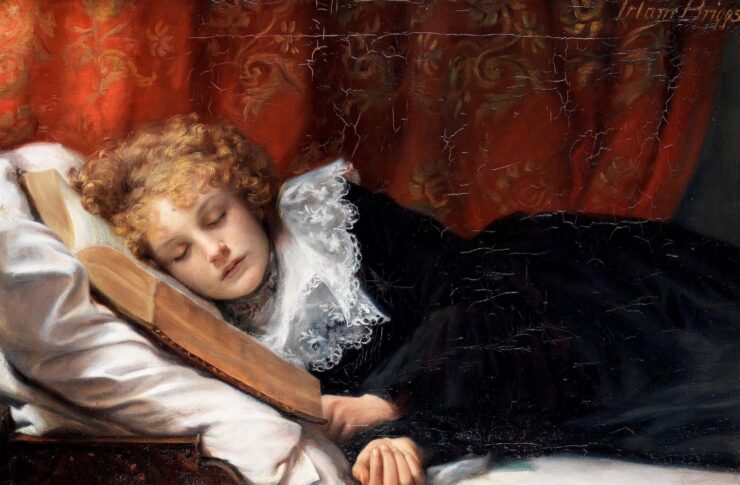

Why do we keep anything? Why do we choose anything? Everything we do says something about who we are, what we value, even if all we can say in a given moment is that we’re tired and worn out and just need soft pants and a book we know every word of already, a book we could follow along with while half asleep. You don’t have to keep books to be a reader. And you certainly don’t need a reason to keep them. But if you grew up on stories, if your memories are infused with what you read where and when and who you talked about it with, books aren’t that different from photographs. They remind you how, and when, and why, and what you did with that knowledge, and how it fits into your life even now.

You could substitute records, or movies, for books; more likely, you have some of each. If you are a collector at heart, you collect things that matter. And for some of us, that’s stories, most of all.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.

When my wife was a child, she taped index cards in the backs of her books because that’s what libraries did, and checked them out to her stuffed animals. I think she really wants to be your friend now … ?

I have a lovely t-shirt, embellished with a dragon (a reading dragon, of course), that proclaims “It isn’t hoarding if it’s books”. These are words to live by.

@2 yes

yes indeed

It is an early reader called Tuggy

Mine is Professor Diggins’ Dragons by Felice Holman. I read it in South Texas in 1967 and became absolutely determined to live on the beach in the Northeast so I could have a clambake.

The boardwalk’s in the way or I could see the beach and the North Atlantic, but it’s long years since the clambake was a safe or even legal thing to do.

I think the oldest book on my shelves is a well worn first edition hardcover of The Silmarillion that was a Christmas present when I was 12. Lost the dust jacket long ago. My copy of The Living Sea by Cousteau is of a similar vintage.

My childhood (falling apart) books are eclectic: an Avon paperback of White Fang that I bought at a school book fair when I was 9 (if I open it twill dissolve into a flurry of pages), a large board book of The Snow Queen that is missing its cover (graced by a 3D insert), and a paperback copy of Chicken Soup With Rice that has a picture of the author pasted on the title page. I cut out the picture from the newsprint brochure I got from my teacher and pasted it as instructed on the order form!

I recently found a copy of the Sendak book, same edition as mine, and gifted it to my granddaughter. I look forward to reciting it from memory with her!

Growing up, the single bookshelf in our Washington Heights Manhattan apartment was a shelf under the living room’s easy chair light table. An English and a German / English dictionary, a few novels – in German – constituted the books of an immigrant couple.

When my brother and I started school, my parents decided, at considerable financial sacrifice, to purchase a set of Encyclopedia Britannica from a door-to-door salesman, buying the multi-volume series on a monthly payment plan. Then they supplemented it by buying the book of The Year in Review from 1947 through 1952. It helped us through grammar school and for me became the magic carpet to a life-long passion for books. The Encyclopedia became travel to foreign places and a time capsule as well.

During my grammar school years, I frequented the New York Public Library’s Fort Washington branch on 179th Street, taking out the limit each week. And at Rice High School I began the same process in the school’s library. Years later, one of the Brothers at Rice told me that the Brothers had decided I had set an all-time school record for borrowing books –a rather unusual accomplishment in a Harlem, Catholic Boys high school known at the time for its track and basketball stars.

From the humble beginnings of sports books stuck in my shelf in the bedroom I shared with my brother, my library today reflects my literary wealth. 500 to 575 books – about 545 at the moment. They have all been read at least once. They are my legacy and my treasure, to be shared and left to family and friends.

They carry my name and when I read them the first time. Most are annotated with my comments / observations / agreements / disagreements, or flagged with post its. (I don’t take books out of public libraries anymore. I can’t resist the urge to brand them.)

I don’t use the Dewey Decimal System (and most libraries today have moved away from it), but rather organize my shelves by interest groups. These include: baseball, U.S. history (especially Civil War), religion, opera and classical music, travel books (especially arts and museums), China, biographies, nature and gardening.

A shelf is reserved for author-autographed books, books admired for their content and who authored them. A few noteworthy ones are books signed by George Mitchell, Ed Koch, Madeline Albright, Peter Uberroth and Charles Kuralt.

Among the books that I especially treasure are: Pope John XXIII Journal of a Soul, Hal Borland, Book of Days, Dominique Lapierre City of Joy, any of Pete Hamill, Roger Angell or Fulton Sheen’s books as well as the Thomas Cahill series on early civilization and Jane Auel’s first book Clan of the Cave Bear.

The books are supplemented with shelves filled with librettos, baseball game score cards, selected magazines marked with an S for Save. These include a handful of National Geographics, Fine Gardening, American Scholar, Opera News, the Futurist and any containing articles or commentaries I have had published.

There are very few fiction books, a few historical novels perhaps, and hardly any mysteries, nothing on movies or dance, no classics (Shakespeare, or Greek or Roman mythologies). My library defines me and shows my limitations.

Periodically, I cull my books out and parting is difficult. Those leaving are earmarked for individuals, those with similar interests or to encourage someone’s exploration.

A couple of postscripts which underscore my feelings as well.

On my desk I have a paper weight, engraved with a message from Thomas Jefferson to John Adams in 1815, “I cannot live without books”.

Recently I came across this short essay, written by Yuan Mei (1716-1797) on Student Huang’s Borrowing of Books.

“The student, Huang Yunxiu, asked to borrow some books from me and I, master of Sui Garden, gave them to him with the following admonition: If you don’t borrow books, you can’t read them. Have you not heard about those who collect books? The ‘Seven Categories’ and the ‘Four Divisions’ were imperial collections, but how many emperors actually read them? Books fill the homes of the rich and the honored to the very rafters, but how many of the rich and the honored actually read them? As for all the fathers and grandfathers who have amassed books only to see their sons and grandsons throw them away, there is no need to discuss it.

But it’s not just books that are treated like this; everything under heaven is treated the same way. If we manage to borrow something that is not our own, we worry that someone will force us to give it back and so we fondle it fearfully without end, saying, ‘Today I have it; tomorrow it may be gone and then I won’t see it any more!’ If it’s something that already belongs to us, then we wrap it up and put it on a high shelf, storing it away and saying, ‘I’ll leave it there for the time being and take a peek at it later on.’

When I was young, I loved books but my father was poor, so it was hard to get a hold of them. There was a Mr. Zhang who had a rich collection of books; I went to borrow some from him but he wouldn’t give me any. When I returned home, I had a dream about my unsuccessful attempt to borrow books, which shows how eager my desire was. Thus, when I did get to read something, I invariably remembered it. After I became an official and was established in my own residence, as I spent out my salary the books came pouring in till they were piled up everywhere in great profusion and the scrolls and tomes were covered with silverfish and cobwebs. Later I would sigh with admiration at the attentiveness with which those who borrowed books read them and think how precious the months and years of one’s youth are.

Now Student Huang, you are poor like I used to be and you borrow books like I used to. It would seem that the only difference is that I share my books with you whereas Mr. Zhang was stingy with his books to me. But was I unfortunate to have encountered Mr. Zhang? And are you fortunate to have encountered me? To know whether someone is fortunate or not, it depends on how diligently he reads the books he has borrowed and how swiftly he returns them. To explain my thoughts on borrowing, I am sending this note along with the books.”

The oldest book I own is a big encyclopedia type book of fairy tales i stole from my oldest brother’s library. The first book I would always read when i would go into his room.I told him it would be mine someday :)

I think the oldest book I own is the copy of The Sneetches and Other Stories by Dr. Seuss that Mom read to us/we read as children. It has no spine & the covers are held together with thread. I’m never getting rid of it & I’m not even overly sentimental. But that book is a reminder of my childhood, it’s a reminder of the importance of reading at a young age, & I just really love the stories inside.

My oldest books are probably three very battered volumes of Lord of the Rings with the covers taped on with packing tape. I have other old books lying around my house, but those are the most beloved.

When my parents finally built their own house, they made sure that one of the rooms was a library. We moved just before I turned five. Now 25 years later, that room has no more space for books so we store our books upstairs in our bedrooms and in boxes along the corridor. I am the only one in the house who still collects books. Games and streaming websites have diverted my siblings’ attention from books but if I buy books that they like, they will still read it. So our collection consists of science fiction, fantasy and romance novels that my parents had before their marriage, children’s books that they bought for us to learn reading, series that we read during our respective childhoods, series that I like and still continue to read and an ever-growing collection of light novels and manga translated from Japanese that I can now afford since I am now employed as a librarian.

My first personal books were a set of story books that came with the encyclopedia set my parents got for me when I was very young. I loved those books and took them with me when I got my first apartment at 19. All during college, I kept those books, and all the books I read but after moving all those boxes of books about 20 times I decided to downsize. I have traded physical book hoarding for e-book hoarding. My library is actually portable now and the local library got some great science fiction titles.

The first chapter book I remember reading that hooked me into sf/f was “Do-It-Yourself Magic,” by Ruth Chew. I don’t have the original, but bought an old tattered copy online a few years ago and it has since been happily lording over the rest of my sf/f library as the OG. I used to save all the fantasy books and yearn for a castle-sized library, but nowadays, after many many moves and the realization that I will never own a castle, I only collect the books I want to lend out.