I watched Blade Runner for the first time this week. Since I have apparently been living in a cave for the past few decades, I thought that Blade Runner was kind of like Tron but with more Harrison Ford, and less neon, and maybe a few more tricky questions about What Is The Nature Of Man.

That is the movie I was expecting.

That is not the movie I saw.

I told a lot of people that I was going to watch Blade Runner for the first time, because I know that people have opinions about Blade Runner. All of them gave me a few watery opinions to keep in mind going in—nothing that would spoil me, but things that would help me understand what they assured me would be a Very Strange Film.

None of them told me the right things, though. So, in case you are like me and have been living in a cave and have never seen Blade Runner before and are considering watching it, I will tell you a little about it.

There are cops, and there are little people.

There is a whole class of slaves. It is illegal for them to escape slavery. The cops are supposed to murder the slaves if they escape, because there is a risk that they will start to think they’re people. But the cops know that the slaves are not people, so it’s okay to murder them. The greatest danger, the thing the cops are supposed to prevent, is that the slaves will try to assimilate into the society that relies on their labor.

Assimilation is designed to be impossible. There are tests. Impossible tests with impossible questions and impossible answers. The tests measure empathy. It is not about having enough empathy, but about having empathy for the correct things. If you do not have enough empathy for the correct things, you will be murdered by a cop who does have empathy for the correct things.

In Blade Runner, an absurdly young Harrison Ford is a hard-boiled, world-weary kind of man named Deckard, and he is given a choice. He can be exactly as small as everyone is, or he can catch some escaped slaves for the police. He decides to catch the escaped slaves.

Except that ‘catch’ means ‘retire,’ and ‘retire’ means ‘murder.’

Deckard feels that he has no choice in this matter. He says it himself, and the person giving him the choice confirms that he is correct: no choice. But of course, there is always a choice. Certainly, the escaped slaves who he is chasing see that there is a choice. He can be power or he can be vulnerable to power. He chooses power. And power means murder.

The first such murder we witness is that of a woman who escaped slavery and came to Earth. She has found herself a job. It’s a degrading job, a job that even the hard-boiled, world-weary Deckard flinches away from watching. But it’s a job. She is participating in society. She is working. She’s doing the things that she has to do in order to be a part of the world that she risked everything to reach.

Deckard comes to her workplace. He finds her there, and he knows what she is, and she runs away from him because she knows what cops do to women like her. He chases her through the street and corners her. He aims his gun at her through a crowd of people. He squints. He takes a second too long to decide whether to shoot. She runs again.

(Nobody tells you about that part, when you tell them you’re about to watch Blade Runner for the first time. They tell you about all the different versions, and they tell you about the ambiguity of the ending, and they tell you about the fact that all the effects are practical effects. But nobody tells you about the part where a cop aims a loaded firearm into a crowd of people and tries to decide whether it’s worth risking their lives in order to murder an escaped slave.)

She runs, and then he corners her again, and then he shoots her. He shoots her in the back while she’s running away from him, running from death with so much panic that she crashes right through a shopfront window. Glass rains down around her, and she is dead. Not a dead person, of course. Because, as we have been told, she is not a person—they are not people. But she is dead, and when death happens in public, people will come to look. A small crowd begins to gather.

And then a police vehicle hovers overhead, and the police vehicle repeats the same two words over and over, in the same tone the crossing signal uses to prompt those who can’t see the walk sign: Move on, move on, move on.

So the crowd moves on. The story moves on. And Deckard moves on.

He still has work to do. One down. The rest to go.

He murders other escaped slaves before the end of the film. He finds where they are hiding, and he murders them.

It is important, in the world of the film, to remember that the things he is murdering are not people. That it is their own fault for seeking free lives. That the cops are just doing their jobs.

It is important to remember to have empathy for the right things.

There is one escaped slave who Deckard does not murder. She asks him if he thinks she could escape to the North, and he says no. Whether that is true or not, we as the audience do not get to find out, because she does not escape. She does not escape because he decides to keep her. He is asked to murder her, and instead he decides to keep her for his own.

(Nobody warns you about that part when you tell them you’re about to watch Blade Runner for the first time. They tell you to watch for the origami, and they tell you that you won’t believe the cast, and they tell you about the celebrities who have been asked to take the Voight-Kampff test. But nobody warns you about the part where a cop convinces a slave that she cannot escape unless he is allowed to keep her. Nobody warns you about that part.)

Blade Runner does not ask us to sympathize with Deckard. At least, not in the version I watched, which was the Final Cut. I am told that there are other cuts which were deemed more palatable to theatre audiences at the time of release. Those cuts, I am told, reframe the man who chases a terrified escaped slave through the streets of a futuristic Los Angeles and then puts bullets into her back. They allow us to believe that he is a good guy doing a hard but necessary job, and that the hard but necessary job is hard because he is good. They allow us to believe that it is possible to be a good guy while doing that kind of a job.

This is a thing that it is very tempting to believe. It is a thing that we are accustomed to believing. It is as familiar as coming home.

Most people told me the same thing, when I said that I was going to come out of my cave and watch Blade Runner for the first time. When they were giving me their watery opinions so I’d be prepared for what I was about to see, they all said: “It’s a Very Strange Movie.”

They weren’t wrong. Not exactly. Not in the thing that they meant, which is that it is bizarre. They weren’t wrong about that. It is bizarre. The movie itself is ambiguous and nuanced and asks a lot of the audience. Asks too much of the audience, if you agree with the studio executives who released the original, theatrical cut. It is baffling and beautiful and terrible and tempting. It’s Surrealist Science Fiction Pulp Noir—it has to be weird and unsettling. That’s the genre.

But I would not call the world of Blade Runner strange, because it’s the opposite of strange. It’s familiar. If you subtract the flying cars and the jets of flame shooting out of the top of Los Angeles buildings, it’s not a far-off place. It’s fortunes earned off the backs of slaves, and deciding who gets to count as human. It’s impossible tests with impossible questions and impossible answers. It’s having empathy for the right things if you know what’s good for you. It’s death for those who seek freedom.

It’s a cop shooting a fleeing woman in the middle of the street, and a world where the city is subject to repeated klaxon call: move on, move on, move on.

It’s not so very strange to me.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Her work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. She is a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to her work here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Her debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Her work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. She is a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to her work here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Her debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Beautifully thoughtful. Thank you.

Omitted from this account: the slaves have already murdered a very large number of innocent people; they have come to Earth with the intention of killing at least one and probably several more; and this is precisely what they do.

And they haven’t come to Earth in order to find jobs and become productive members of society – if they’d wanted to do that, they could have done it and the blade runners would never have come near them. They’ve come in order to kill people if they don’t get their way. The first thing we see them do in the film is kill. Deckard never, at any point in the film, kills a replicant who hasn’t tried to kill him first.

Why do they do this? Because, as we’re told from the very start, they don’t have empathy. A human hearing a story about suffering has an emotional response. We can’t help it. Even if it’s not a story about anyone we care about or even know, even if we know it’s a made-up story, we still respond. Replicants don’t, which means they’re sociopaths; they can look at a person in agony (like the Chinese eye specialist they torture) and feel exactly as much emotional reaction as you would feel from looking at a running shoe or a cabbage.

They’re trying to give themselves emotions, that’s the point of Leon’s collection of photos, just like a sociopath practices smiling in the mirror so he can blend in among normal people, but they only really have a few – fear of death, and desire for revenge, which is what has driven them to Earth in the first place.

The tragedy is not that they’re just like people and they’re being hunted down; that’s way too simplistic a reading. The tragedy is that they have been deliberately built to not be just like people, and they want to be and don’t know how.

I’ve never thought of it that way before.

but like @2 said, they’re robots who have all the empathy of a sociopath, and they’ve killed. Blade runners are there when the replicants become a problem. Tyrell designed them with a four lifespan, after which they start to degrade them shut down as we see through the film. Roy’s mission is to seek out their creator for more life. The tragic part is that Tyrell doesn’t give him what he wants which is where batty kills him.

we can have empathy because we’re human, Deckard is empathetic because he’s human. Roy, pris, Leon, they kill to get to their creator and when he can’t give them what they want they kill him. They aren’t slaves, they’re victims of design.

maybe slaves to design.

@3 – what a truly comforting smokescreen you have. I’m rather sickeningly amused to wonder what you think a human born adult, dying, and enslaved would actually do differently.

Thank you for the perspective Sarah. I’m probably one of those people that would have babbled about origami unicorns, mainly because this is a very uncomfortable film to watch. It is very hard to have sympathy for some characters, and the easy thing to do is pretend they all deserve some, or none do. No one wants to look too deeply into a dark mirror like that, and wonder which member of that hellscape they’d end up as.

Interesting article. I watched Blade Runner for the first time a few weeks ago (I wanted to finally see the original before watching the sequel), and I did not care much for the movie but I couldn’t really put a finger on why. I get that it was groundbreaking and visionary for its time; and it was rather beautifully shot and I assume that the acting gave off the appropriately eerie, noir feel that Ridley Scott was going for. But I did not have the fascination or reverence for the movie that my other friends who love SFF have.

I agree with both #3 and OP about this. This movie’s other title might as well be “No one is free from guilt” or “I had no other choice”. Looking back at slavery in America say we have a situation, one that actually has happened, where a slave(s) killed either out of fear of punishment or in the hope of freedom. It would be easy to sympathize with their dilemma even though the slave is now a murderer. Would an officer be justified in then killing a slave who felt driven to commit murder to save their own life? My analogy doesn’t quite compare since we’re comparing humans to AI’s, but while there’s a difference in humanity vs machine there’s no difference with intent. And the intention behind these characters, just like the intention behind the real life violence that we’re really talking about here, is that everyone feels justified in their choices of violence or turning a blind eye to a system that promotes and numbs us to it.

To me the ultimate tragedy isn’t in the perverse choices fictional characters are written into or into the real life class differences and poverty and crime and mass shootings. The tragedy is in the depths to which we justify wrongdoing as right. It’s in the intention that begins a line of consequences. Why would you even want to own a slave? Why would you even want to shoot a woman in the back? Why would you want to even own a gun? Why would you even want to hurt others? What is driving you to even begin your line of intention that ends with justifying wrongdoing?

@@.-@ Loungeshep what makes you say that Deckard is human? (hope I’m not opening a can of worms here). I don’t remember the theatrical cut well any more, and even the final cut was a while ago, but it seemed almost too clear that Deckard was a replicant.

IIRC we have things like:

– nothing verifiable about Deckard’s past; and he currently lives alone

– we see his eyes flash red. Something that we only see in replicants

– the shared fake memories or dreams that both he and Rachel have

– Deckard never answers when Rachel asks him if he passed the Voigt-Kampf test himself

– his partner tells him at the end that he’s done a “man’s job”, ie: that he performed just as well as a real man

– it’s the lacking (or damped) empathy that allows Deckard to hunt down and kill replicants

I have always hated this movie, and until now I had trouble figuring out why. Anyway, thank you, great review and perspective.

Yeah, I’ve never been a fan of the Deckard as replicant theory. It’s like the movie is hitting the audience over the head with the message: we’re not so different you and I because…we’re really the same creation! Really, you don’t need to underline the theme like that, Mr. Scott. Batty saving Deckard, then giving the ‘tears in rain’ speech do the same job and in a more subtle, poetic way.

And on a practical level, why would the police use such a weak model if they were using replicant hunters? Deckard gets beaten up by every single replicant he comes across. Even Pris could’ve broken his neck had she not decided to play with his nostrils.

So if a dog tries to act like a human, despite not being one, should we consider it a human being?

Replicants are created beings. They aren’t born, they don’t have emotions, their memories are fake. You draw a very blurry line in the sand about what constitutes “human” if you assume that any biological life form that can mimic a human, is human.

OMGGGGGGGgggggggggggggggggg

@11 I think you’re mixing up the movie & the book. The book makes it pretty clear that, whatever legitimate claims to sympathy they may have, they don’t have empathy; that’s part of the point with the scene where they cut the spider’s legs off and have no idea why the human in the room is so upset.

The movie, on the other hand, makes it clear that, whatever the underlining intent/programming is, they do have emotions.

@@.-@ I’m a recent viewer myself & have only seen it once, but I’m pretty sure Roy killed Tyrell not because he couldn’t extend the Replicant’s lives but because he couldn’t be bothered to care. It wasn’t just “I can’t” it was “So what?” BOTH Roy and Pris were doomed, and Tyrell was sitting there telling Roy to be glad he lived at all.

The replicants are slaves. Deckard is a slave. The people in power want this state to continue. The replicants are doomed; they have a set and limited lifespan. They want to avoid this doom so they at least have empathy for themselves and seem to have a group cohesion. They don’t have much empathy for the people who put them into this situation, but then, who would?

There is at least one slave who isn’t doomed and needs to get out of town. Is Deckard keeping her or is she keeping him? I don’t know; maybe we’ll find out some more about that.

Who are the people and who aren’t the people–if, indeed anyone isn’t or is a person. These are questions.

Personally, I would have fought for the replicants to not be forced into the condition we find them in and would want them to escape the situation that they are in.

Sarah is correct–everyone is in a very strange place whose familiarity comprises the broken dream of reality.

“The greatest danger, the thing the cops are supposed to prevent, is that the slaves will try to assimilate into the society that relies on their labor.”

That’s the “greatest danger”? I think the people they murdered might disagree…

If I forcibly put a human into a huge shredder against their will it is murder.

If I forcibly put my old computer into a huge shredder it is recycling.

Although I found the article interesting I do think that repeatedly making it a point of calling the deaths of replicants murder, and calling them slaves really misses the point of what the movie is all about.

The movie leaves it up to the viewer to decide what it means to be human, the author of the article makes it sound like we don’t have that choice, they are slaves and it is murder. How human of her :)

thanks for this useful analysis. One of this movie’s points is that Deckard realizes that his job is murdering people and decides both to quit and to steal a slave from the man keeping her as a pet, in ignorance of her true origin. I loved that the movie showed both the replicants’ violence and the reasons for it: their exploitation (casual remarks like “standard pleasure model”) and their rage at their built-in death sentences. The violence by both Deckard and the replicants is appropriately horrifying: each episode of it, no matter the victim, shows a person being hurt or killed. As to empathy, how mature would you be if you lived for only 4 years, and how much empathy should a slave feel with a master? (I still don’t feel too much sorrow at the death of Tyrell, the monster father.)

The movie also includes my favorite line ever, from Edward James Olmos: “It’s a pity she won’t live! Then again, who does?”

@8. I knew I”d get someone with that. I always felt that Deckard was human, but he was beaten down and exhausted from a lifetime of living in the conditions of Los Angeles and hunting and killing replicants.

Also the book the movie is based off of Deckard was human. The idea was that the Replicants were being more human than the humans who were worn down by society and their surroundings that the humans were more robotic than the robots.

@17 “I still don’t feel too much sorrow at the death of Tyrell, the monster father.”

How about the death of Sebastien? After all he welcomed them into his home, befriended them in his own weird sort of way and even got them past Tyrell’s security and his thanks? But hey it is the world we live in, no one (I guess that now includes replicants) is personally responsible for anything they do any more. I was beat as a child, I ate too many Twinkies, the devil made me do it.

Obviously this reviewer is a replicant.

Guys. Guys. There is no one “correct” reading of Blade Runner. Blade Runner can be about the tragedy of facsimiles of humans trying to be human–the most literal (and therefor simplistic) reading of the film–and also about the way that capitalist societies dehumanize and enslave workers, and keep them in line using the state’s monopoly on violence. If you want to continue enjoying Blade Runner on the literal level no one is stopping you, but don’t fault Sarah for trying to dip a wee bit deeper.

Imo the purpose of all good sci-fi is to hold a mirror up to modern society, and Sarah does a great job of explaining how Blade Runner does that. The fact that Blade Runner is relevant to issues of racialized personhood and police violence in 2017 is exactly what makes it such a great film. (Making a navel-gazing wankfest about the nature of humanity is a lot “easier” than hard-hitting social commentary, if you ask me.) I have yet to watch the movie myself, but this article may have convinced me that I need to.

@21 Oh man you haven’t seen it??? I have to be honest for me after I had seen it I wasn’t sure I liked it. It is a hard movie to like on the surface, it took time for me to think about it before I learned to really embrace it. However when I re-watch it, it is still a bit painful to take. There is something about it that just makes it hard to watch, not in a bad way but in an emotional way.

This is an excellent piece, thank you. I was thinking a couple of the same thoughts rewatching it the other night but your thoughts streamlined and crystallized things for me.

it does seem like the point of the movie and the book and a whole lot of pkd’s work

what makes someone human?

what validates a life?

cue descartes

As always, we ask that you please keep the tone of this discussion civil and constructive in tone, and avoid personal attacks and rude, aggressive, and dismissive comments. The full Moderation Policy can be found here.

I think comparing the replicants of the movie-who were sociopaths as Ajay pointed out- is to insult the slaves of American history who were actual people. The cop who destroys rogue robots was the plot of Runaway starring Tom Selleck.

The movie presents the audience with the question “what does it mean to be human” and the answer is empathy. But it’s not only the ability to feel empathy that makes you human, it humanizes those around you, making them human to you, too. This is why we treat our dogs better than strangers in most cases. Our dogs are the subject of our empathy, so they are treated as humans. This is what Deckard learns with Rachel, I think.

But I do agree with the final conclusion of the article. To paraphrase: we’re living in a science fiction dystopia, and that kinda sucks.

This is a phenomenal review/counter-interpretation of Blade Runner, poetically and gloriously written. It’s also one I happen to disagree with. Not the part about how resonant it is today because of police brutality and slavery, but the part that slides over what the replicants do.

Specifically, the cold-blooded, completely unnecessary murder of J. F. Sebastian (which granted took place offscreen and may have been missed on a first viewing), who both treated the replicants well–indeed, treated them as equals– and was utterly harmless to them. Maybe it’s just because I identify with Sebastian more than any other character in the film, but I think it complicates the reinterpretation.

The reason the replicants lack empathy is that they aren’t given a chance to develop it. That is also why they have a limit on their lifespan.

if the only way to tell that someone is a replicant is that they fail a Voight-Kampf test and they will pass that test if only given time, then in what way are they not people?

If the replicants are so lacking in emotion, why did they escape? Why would an emotionless machine want a better life, or revenge? I thought the implication that they do have some level of emotion was pretty clear.

But it’s nice to know I’m not alone in hating this movie.

I love the movie, by the way.

I have a ton of issues with this groundbreaking film, and I’m not sure whether or not Ridley Scott and Hampton Francher didn’t intend for it to be exactly that: a violent and disturbing film about power and access versus humanity, and exactly what it means to be human. I saw this movie in its original form, the theatrical release, with the terrible voiceover. In spite of that I carried away a sense of doom and hope for the protagonist and his chosen ward. It’s not an easy film to watch.

In this “future noir, Rick Deckard is deprived of his humanity by his vocation as surely as the replicants’ is by design. The gender power dynamic between Rick and Rachel is clearly apparent in the “love scene” which I viewed as rape. She is completely at his mercy. He directs her what to say and she complies. She has no option but to submit, succumb to his will. It’s classic patriarchy where the “lesser” woman is entirely at the disposal of the “superior” man, the “master,” in this case she is literally at his mercy; as she puts it so succinctly, “I am the business.” His business, the killing of replicants.

The violence perpetrated by all is horrifying. What is depicted on screen is brutal. Leon’s shooting of Holden sets the violence in motion. Deckard may be a reluctant participant, but the “retiring” of Zhora is clearly premeditated and murder. The killing of Leon by Rachel to save Deckard is possibly an act of self preservation, as she must suspect that Deckard is sympathetic of her plight, since she chooses to hide out with him, which is likely her only course of action after escaping from her “keeper” and creator, (or “father” and Roy puts it, another signpost of patriarchy.) Tyrell’s murder by Roy is quite gruesome, and the sight of Sebastian attempting to flee from Batty and certain demise is squeamishly pathetic and awful.

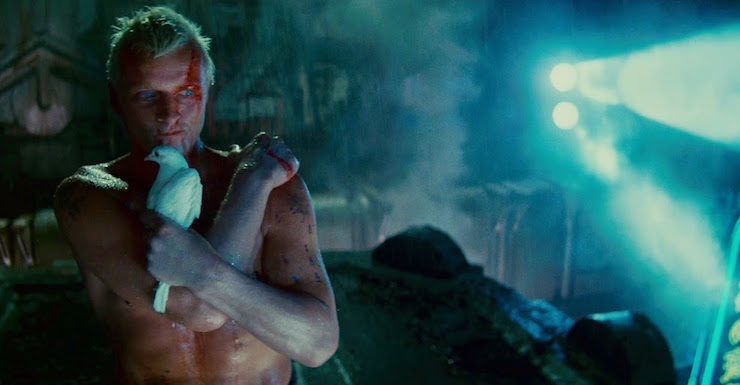

The battle between Pris and Deckard, followed by Rick’s confrontation with Roy are the most violent segments of the film. Pris’ death is a rage against the unfairness of her fate. Roy’s sense of loss here is palpable: He loved her. The sudden mercy that Batty extends to Rick in the end shines a light on what it means to be truly human. Here, in his mortality, he chooses to save the man sent to kill him. The man who has killed his compatriots. His “natural” enemy. “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it? That’s what it is to be a slave.” And with that he pulls Deckard to safety, and speaks to him of his short life as he dies.

This shining act highlights the pointlessness of the replicant murders as they all had a terminal date that would eventually end their existence. It also points to the futility of their quest for more life. One only gets so long to live, and must make the most of it, for in the end, all things must pass.

That Deckard chooses to escape his fate as Bladerunner and that of Rachel as replicant by fleeing with her is an indication of his returning humanity. That the film is unresolved, and without a happy ending, is what makes it powerful. By ending the note on such desperate hope, leaving one with more questions than answers, is why, to my mind, it deserves to be a classic.

The subsequent releases have only solidified and strengthened my original impression of this seminal Science Fiction film. It is at once disturbing and enlightening, and deserves all the respect it has garnered, and much of the criticism. There are very few filmmakers that could have created such a movie. Hats off to Ridley Scott.

@28

Why is it sociopathic for the replicants not to recognize the value of human life, but it’s perfectly normal for Deckard and Gaff and the others to not recognize the value of replicant life? You can’t have it both ways. If Baty is a sociopath, so is every character in the movie other than Sebastian.

A really great, incredibly thoughtful look at elements of the film that far too many viewers have overlooked for far too long.

32: oh, they definitely have some emotions. But emotions, desires, don’t make you human. Mice have emotions. What the replicants don’t have is empathy. That’s literally the whole point of the VK test. If you listen to the questions, they’re specifically about empathy.

And it’s interesting that the review itself navigates the limits of empathy… the pretty killers on the screen are the ones we sympathise with, the ugly ones that they kill deserved to die (and barely even deserve to be mentioned). The replicates are creepy like Pratchett elves… they toy with their victims before murdering them.

12: “They want to avoid this doom so they at least have empathy for themselves…”

That… really isn’t what empathy means. It’s like saying “how can you say I’m not generous? Look at this amazing car I bought for myself!” Empathy by definition has to be for others!

Such an insightful piece, yet no mention of the scene where Deckard sexually assaults? That made me realize he has to be human – he treats nonhumans as nonhuman.

comments section full of “but blade runner can be interpreted in many ways! so you’re wrong in saying your interpretation, because they’re artificial :) :) :)”

“Specifically, the cold-blooded, completely unnecessary murder of J. F. Sebastian (which granted took place offscreen and may have been missed on a first viewing), who both treated the replicants well–indeed, treated them as equals– and was utterly harmless to them.”

J. F. is also a lot like those replicants – his life expectancy is much lower than other people, for he has this Methuselah syndrome and he cannot fit in. So in a way Roy Batty murders one of his own kind. His talk of staying together is just a talk.

“There is no one “correct” reading of Blade Runner. Blade Runner can be about the tragedy of facsimiles of humans trying to be human–the most literal (and therefor simplistic) reading of the film–and also about the way that capitalist societies dehumanize and enslave workers, and keep them in line using the state’s monopoly on violence.” – exactly!

Also I’m quite envious – I just watch a movie and I like it or not. No really deep thoughts after :(

IIRC Ridley Scott made this movie with “Deckard=replicant” on his mind, while Harrison Ford made it with “Deckard=human” on his mind. Maybe it’s even better that way.

But what Sarah Gailey didn’t mention specifically, was that Deckard not only “keeps Rachel as a pet” – he also coerce her into having sex with him. It’s all very “darklightromantic”-y filmed, but it’s essentially still rape.

@@@@@ 17 stald

what part of “The violence by both Deckard and the replicants is appropriately horrifying” was unclear?

@@@@@ 21 blah

very well said.

A review I read of “Ex Machina” contained a line that struck me:

I think that applies in spades to the replicants in the Blade Runner universe.

Thanks so much for highlighting this aspect of the film. Most analyses tend to focus on the “nature of humanity” themes of the movie (probably because those themes are the ones more directly and personally relevant to a white writer) while ignoring the more political themes.

The 1982 theatrical version was different in two significant ways: it had a tacked-on bit of optimism at the very end, and they added some voiceover narration in post-production. Ford really hated the narration, and his contempt is very evident in his reading. The narration is mostly pointless; it explicitly tells us things that should be obvious (such as “Gaff didn’t like me much” and “A cop like Bryant using the term ‘skin-job’ was kinda like a 20th century cop calling a black person a n***** ”

Pretty much everyone all over the world who saw Blade Runner, saw that this was exactly what the plot was about – how the question of what a human is can be used to dehumanise and enslave. It’s not subtle. It’s not hidden. It’s out there front and center, from the scenes where the replicants are killed to the “love story” and it’s seriously rape-like scene, to the question of whether or not the central character is a human or a house slave.

That nobody you spoke to in the US before writing the review saw that is the really telling thing.

Very insightful, thanks

Something which really struck me when rewatching to see if suitable for my kids is that Deckard effectively rapes Rachel in a way which I found eliminated any sympathy I felt for him. The whole ‘romance’ element of the film really disgusted me in a way it hadn’t before.

Also concluded that scene more than the overtly violent ones put the film off the shelf for now

“Roy feels human-like emotions and has aspirations, but doesn’t get a human lifespan, Knight said. Roy is aware that, like the other replicants, he has been built to die after a mere four years, which understandably enrages him.

So replicants arguably do feel emotions, and they have memories. Does that make them human? For Schneider, a definitive answer doesn’t necessarily matter. The replicants share enough qualities with humans that they deserve protection. “It’s a very strong case for treating [a non-human] with the same legal rights we give a human. We wouldn’t call [Rachel] a human, but maybe a person,” she says.”

from:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/are-blade-runners-replicants-human-descartes-and-locke-have-some-thoughts-180965097/

I feel that this film, and the book, needs to be viewed in the context of Philip K Dick’s ouvre of mostly short stories posing difficult existential questions, which as we can see create a wide spectrum of opinion. Magazines like Science Fiction and Analog often covered such topics. The operative word I believe is ‘dystopian’.

Unfortunately, one person’s Dystopia, is another’s Paradise. Like Western liberal democracy versus a Sharia Caliphate. Both, if you wish, held in place by state control of violence and an interpretation of law, human versus theocratic. Equally, with the potential for tyranny, depending on one’s perspective.

As contrasting but similar narratives, it might be useful for the readers to compare Blade Runner with AI, I Robot, and Millennium Man.

To repeat what Kameron said:

OMGGGGGGGGGG

And I’d like to include: )*&$%#%^()!!!!!!!!!1!!

because I’d never thought of it this way and it totally adds another dimension to (what might remain) my favorite film, It is an uncomfortable film, for all the reasons the OP said, as well as all the commentators…and I think I love it for that, too.

One point you’ve missed is that Deckard is the only guy they have who is so much of a hardass that he can kill slaves. Watch the first scene again. Holden figures out pretty quickly that Leon is a replicant, but he also sees enough humanity in Leon that he can’t simply execute Leon. Deckard, on the other hand, when he eventually sees the slightest sliver of slave in Rachel, after the longest series of impossible questions he’s ever had to ask, immediattely starts calling her “it”.

The problem with deciding that Deckard is a replicant (as so many people do) is that to do so is to display the same reflexive cruelty as Deckard. He is human, but he is the least humane person they have, so they use him like a slave. Rachel is a replicant, but she is so humane that even the worst bigot in LA (Deckard) can’t bring himself to execute her.

Instead, he agrees to help her escape after she agrees to have sex with him. I’ve been calling that scene a rape for years. Deckard is not a sympathetic character. That we sympathize with this inhumane monster at all is a measure of our humanity as sure as a Voight-Kampf test. These tricks and emotional twists are exactly what make Bladerunner a great film.

Replicants (at least some of them) do have empathy – Roy saves Deckard, after all. And the one of the points of the movie is that replicants are treated with the same lack of empathy that is supposed to separate them from humans. Repeatedly, throughout the film, Roy tries to get the humans he interacts with to empathize with and understand him and what he’s experienced: saying “If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes” to Chew, telling Sebastian “We’ve got a lot in common”, driving home to Deckard “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it? That’s what it is to be a slave” (which was also echoed earlier by Leon’s question to Deckard, “Painful to live in fear, isn’t it?”), and of course his final speech.

Deckard’s realisation of the horrors of his job is his entire arc in this story. And he doesn’t “take” a slave for himself. Rachel asks if she ran north, would he follow her, hunt her down? He says no, but someone would. So instead he goes too, because he doesn’t want to be a killer any more or one of the little people. So he goes with Rachel so they can protect each other, and escape together. The interpretation of the film in this article is way off the mark and ignores heaps of the film in order to push its message. It’s a great article, but it’s not accurate at all.

Beautiful review and response, and that reaction is certainly intended by the work, as with other SF. People should have empathy for all humans, regardless of race, gender, or nationality, and the work can help us see that.

At the same time, most of us also should be able to understand the anti android view as well. Most of us have at least something, whether animals in general, pets, great apes, the disabled, the senile, or fetuses, that we don’t wish to treat as fully human while others do. So part of the specific challenge of the work, like other SF, is in determining exactly what are our reasons for making distinctions and where we draw the boundary.

The greatness of the work is that it encompasses multiple views and multiple things to meditate on, like most great art.

When I was a kid I watched the original Rollerball. I was horrified. I was literally depressed the whole day. I was angry at the movie and the people who made the movie. How could someone THINK of something like this? People killing one another for sport? I grew up thinking only bad people hurt others… not people just doing it for fun, let alone part of their job. When I was in my 30s I watched it again and realized that that WAS the point of the story. As a warning to how callous and thoughtless we could become. Hyper-normalization is what they call it now.

I get the sense some folks are “angry” at Bladerunner in a similar way. Phillip K. Dick (the author from which the movie’s premise is borrowed) was always trying to superimpose the past onto other pasts, presents and possible futures. You’re supposed to see these nuances. Yeah there’s the Replicant angle, but he’s stuffed a lot of baggage into the Replicant story. It’s not just class struggle but also *colonialism*… the idea that we are basically using these living sentient creatures as an extension of our imperialist and *corporatist* designs. And so we talk about things like whether they are “capable of empathy” the same way France and England and later the USA would ask whether African nations, new to Western modes of business, culture, etc. are “capable of Democracy” and so on. Yes, you’re supposed to be unsettled by this. Yes you’re supposed to be the person who asks these questions and then is embarrassed that you actually asked them. And then you get angry. That’s part of the point.

Maybe the writer just didn’t have any actual PKD fans as friends. Or maybe they’re so caught up in the “scifi” part of it, the technology and cool stuff like that. But trust me, most PKD fans are fans because of the layers, the nuances. Look at his other stories like Man in the High Castle where he manipulates an alternate history where you still hate the Nazis but empathize with Nazi characters and are actually *afraid* what might happen if Hitler dies (and yes, again, this is just the “top” of the story, the top layer). You literally catch yourself realizing this and see how these complex layers have huge sway in our lives, our intentions and struggles alike.

I’ve often hoped that the remake of Blade Runner, my favorite movie, would be a retelling of the story from the perspective of the replicants, with them as the protagonists. Because, yes, yes, and yes.

I saw Blade Runner at the movies when it was released and I was 17. I really didn’t get much of it, other then the ending, which is one of my favorite endings. I always saw this as Frankenstien story, fantatical scientists creates a living creature, and the creature becomes the victim, that transforms into a monster and kill’s his creator\father.

The important thing to remember is that, emotionally and mentally, the replicants are infants. So I don’t see them as basic sociopaths. They just don’t know better.

The were specifically designed for tasks – soldier, manual labor, sexual pleasure- and they have end-of-life dates so that they expire before they can learn the emotions and mental processes, or gain a soul, which makes them a human in every way except their conception.

****spoiler alert****

Remember Beaty does develope empathy at the end.

Perhaps people didn’t tell you about the themes you figured out from watching the film because they wanted you to experience it for yourself. I would have been annoyed to have been presented with a description like the above before watching a movie for the first time. Seeing it and coming to the realization of the themes is an important part of the experience. Knowing beforehand it wouldn’t have hurt so much.

It was pretty obvious after seeing it what this film was about in terms of slavery and and humanity and how one defines the other and makes it possible, even when it first came out. This isn’t the first science fiction that examined those ideas (Planet of the Apes, anyone?). But Blade Runner made it hit home hard, didn’t it? Especially coming into it unawares.

So yes, you weren’t warned about it. But because you weren’t, you’ll never forget it. For you that might be a negative, but I think for the general population I’d count that as a positive that they haven’t forgotten. Well, some of them haven’t. I’ve never been able to watch it a second time, but I’ve never had to.

@34 “but the “retiring” of Zhora is clearly premeditated and murder.”

ONLY if you believe Zhora is human. If Zhora is just a machine then it is NOT murder.

I am not saying Zhora is or is not a machine, honestly I still am not sure. What bothered me about the article is it comes across as fact that Replcants are people and that is a choice that has to be made by the viewer.

One last point, there is an old saying. “If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.”

With today’s technology that is clearly NOT true, we can easily create a MACHINE that “looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck” and is NOT a duck.

So if we create a machine that “Looks like a human, walks like a human and talks like a human” is it human????? Before you start tossing around words like murder, slavery and rape then that question has to be answered.

What is human and what is More Human Than Human?

the replicants are searching for a way to extend their lives, as they only function for a given amount of time

Roy wants Tyrell to “fix” him so he doesn’t cease to function, but by their very nature(manufacture?) they are short-lived

the replicants are in survival mode

Lovely piece.

Now… as a big fan of BR, I fully acknowledge it’s a horribly bleak, depressing and cruel movie in many ways. And yet paradoxically, also a really profoundly beautiful film about compassion, mercy and valuing human life. That battle of themes and tone I find endlessly interesting, and I don’t know if it was intentional, but it’s given the movie an undeniable uniqueness, that is probably the real reason for it’s enduring appeal. It’s not a generic film, generic films die unloved and unforgotten. This is a movie that regardless of anything else, is hard to ever forget.

Look… Deckard is 100% a villain protagonist, the replicants absolutely tragic anti-heroes, and the scene with Rachel is horrifying rape that rips me out of the film every time I watch it.

But somehow, a film with all that also features perhaps the most beautiful, meaningful dying speech I’ve ever witnessed in a film. A speech that so perfectly encapsulates the tragedy of death, and of robbing one of their right to live and experience precious ‘moments.’ I can’t believe any film with such a moment, isn’t at least on some level aware of how nasty and horrible it’s ‘heroes’ are and how vindicated the ‘villains’ are in their desperate quest for life and liberty.

Blade Runner may very well be a hateful film overall. But in the end, it’s message is one of empathy and mercy. A paradox worthy of science fiction itself.

Clearly stated and spot-on.

I’ve watched Blade Runner easily 100 times since it came out (almost always the original cut). If I had to pick a favorite movie, Blade Runner would be it. One reason I like it so much — and have watched it so much — is that I pretty much pick up on something new every time I watch it. And I generally enjoy reading the opinions of other people to see if there’s something I missed.

This particular article certainly gives the movie a new slant, and I enjoyed reading it. But I can’t say I agree with the interpretation. The replicants were not just another version of humans who simply wanted a job on Earth (even if it meant dancing in strip joints with an artificial boa constrictor wrapped around your neck). They had taken over a spaceship and killed the crew in order to get to Earth. That woman that Deckard killed had been part of an off world “kick-murder squad”…she was an assassin. They were not back on Earth to be anyone’s nice next door neighbors.

Again, interesting take on the movie, but I really don’t consider it exactly spot on.

It’s really interesting, reading these comments, to see the article is functioning as a sort of Voight-Kampff test of its own in asking people to have a particular empathetic reaction to someone’s reading of the film…

“Who is allowed to be human” is one of those questions Dick wrestled with a lot, and I think the interesting part of Blade Runner is that everyone involved in its making had a slightly different idea of how to draw the line. Which in itself is exceptionally relevant for 2017.

I think some of the commenters here need to revisit the film again. To think that the Replicants are without empathy is ridiculous and counter to most of the film. As the police and Tyrell explain, the Replicants very specifically had the capacity to learn and develop empathy and feelings. Their limited life spans were an artificial barrier put in place specifically as attempt to try to curb this potential. What we learn through the film is that those efforts didn’t work. While the Replicants might not pass the test of eye twitches in response to arbitrary questions about animals, and while they are ruthless in pursuit of their goals, we do see them act out of desperation and self preservation but also they mourn for one another. The limited lifespan was intended to limit their experiences but even in their short time they had enough experience to develop as people. These are not machines pretending to be people. These are people that have had their personhood stunted to make them more effective slaves. It is ridiculous to see commenters here try to compare “retiring” them to recycling their (very much not sentient or self motivating) desktop computers. Most of the time, when dealing with a 3 year old with a developing mind we call them children.

Great article and a good perspective on the subject of the movie. I take this article to be one lens through which you CAN see this movie. A valid opinion. Most of the comments below the article are also valid opinions. So, what value can be gleaned, if all opinions are valid? Lots, especially in the effort of seeing value in opinions that aren’t yours.

For me, this movie was about the birth of the first non-human humanity. Not just artificial intelligence but an entire personality. Now, the love story? Yes definitely, it felt like a 1950’s film noir. Mostly because it was a film noir. I believe that Deckard’s feelings were real, that her feelings for him were also real, but that on both sides of this wonky relationship there was no possibility of pure altruistic love. She needed to love him to survive, he needed to love her to redeem himself. So, he was a brute and she needed him so she accepted her shitty lot in life to spend her remaining span with him. Is this a good story? Well, in some ways yes. From a feminist lens, it suffers in every way that movies of it’s day suffer, and it suffers as movies of it’s genre suffer. It is not progressive on this scale. In terms of slavery, it is as the writer points out above, a great example of how slavery works. Othering, dehumanising, and gaslighting all used to build a society up on the backs of something that really should be treated with respect. They could have just made self operating fork lifts, they didn’t need the rest, but society gave them emotions even if they didn’t give them empathy, so here we are. A fork lift that can feel bad when you leave it to rust, but is also incapable of feeling bad when it runs over a human in the workplace. What were they thinking would happen?

Deckard sought to possess a woman, not a slave. Doesn’t make it right, but I think the writer above has that one detail wrong. Deckard knew she had humanity. He didn’t believe she was a thing or he never would have thrown away his life and livelihood for her.

The test wasn’t for conformity, it was for empathy. If they had empathy they would be as safe as any human to live with, they would do no hurt for they would feel the hurt they did, or understand the hurt they did not just as something to be inflicted but also experienced. The golden rule is written on our brains, not just in our old books. We flinch when others are hurt.

If we accept the hypothesis that Deckard is a replicant (and there is plenty of evidence that he is), he, in fact, doesn’t have a choice. Obeying is part of the programming. That’s why he is able to command Rachel to love him.

As I’ve got older my appreciation for Blade Runner has grown as the main character is clearly the villain of the piece, whilst the replicants are desperately fighting to live.

I think it’s clever that the film plus with your sympathies: when Batty is chasing Deckard we fear for the latter, despite the horrible things he’s done.

Conversely, when Batty dies, who has murdered a number of innocents over the course of the film, it feels like a tragedy.

I am genuinely shocked to see so many people interpreting Deckard’s interaction with Rachel as rape. I think this is a sign of how aware we as a society have become of date rape and the need to obtain consent.

I am absolutely confident that at the time the movie was made, it was not intended to imply rape or sexual assault was taking place, just as I am confident that the vast majority of moviegoers at the time would not have seen it that way. I don’t think the author, the screen writer, the director, or the actor intended for Deckard to be seen as someone that would commit a rape. I can recall no movie reviews at the time alluding to it, and of the many times I saw it and the many conversations I had about it, I don’t remember anyone even suggesting it as a far-out theory.

I also strongly disagree with the notion that replicants are sociopaths and lack empathy. I think that badly misses one of the central plot points, which is that they are capable of a full range of human emotions, but have not been given the time, the parenting, or the socialization to allow them to understand or deal well with what they’re feeling. For example, when Leon is being asked the question about the tortoise, it seems completely clear to me that he’s freaking out because of how distressed he feels at being told he’s ignoring an animal in distress. The test is catching him not because he lacks empathy, but because he can’t handle the empathy he does feel the way an emotionally stable human would.

Here’s a bit of nuance.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a complex &, frankly, rather baffling story — Philip K Dick, after all. It seems as though some folks want to flesh out the film with details drawn from the book.

But the movie is very different from the book.

Replicants (at least some of them) do have empathy – Roy saves Deckard, after all.

Just before his time runs out. That four-year life-span is timed to the second; Roy has a moment of empathy, probably his only one, and then it’s “time to die”.

And why don’t they want the replicants developing empathy, anyway? We’re never told. Maybe because it would make them impossible to tell from humans; after all, the VK test only works on replicants because they don’t have the same emotional responses to suffering. (Look at the torture scene.)

Or maybe because empathy would make it impossible for them to do their jobs. Roy’s a combat type, Zhora is an assassin; lack of empathy’s probably an advantage.

@vmsmith–may I respectfully suggest you watch the sex club scene one more time? It’s quite clear Zora was doing more with the snake than dancing; the club announcer in the film describes her a ‘taking pleasure from the snake’ (as another commentator mentioned above, it was enough to get the hardened Deckard to look away in disgust and shame). It may be a small scene, but important to demonstrate the depths of degradation the replicants were willing to sink to in order to flee the slave/assassin’s life.

Has anyone here seen Christopher Lambert’s Nirvana?

It’s an underrated classic.

For example, when Leon is being asked the question about the tortoise, it seems completely clear to me that he’s freaking out because of how distressed he feels at being told he’s ignoring an animal in distress. The test is catching him not because he lacks empathy, but because he can’t handle the empathy he does feel the way an emotionally stable human would.

Interesting question: is the test catching him? He gets asked the question about the tortoise, there’s a little discussion, then Holden asks him to tell him about his mother, and then Leon shoots Holden. I don’t think there’s any suggestion that Holden realises at any point, from the VK test or anything else, that Leon’s not human, right up to the point where Leon shoots him.

And I think there are a lot of ways to interpret Leon’s response:

1) He’s freaking out because he feels empathy and doesn’t know how to deal with it; maybe, but he shows no empathy at all later on in the film, e.g. when he’s torturing people

2) He’s freaking out because he’s face to face with a blade runner, he doesn’t know the right answer to give, he knows he can’t react the way a human would, and he thinks he’s about to be found out and retired

3) He’s faking freaking out because he’s trying to fake a human emotional response and/or put Holden off balance and disrupt the test; just like you fool a lie detector by making yourself angry deliberately from the start

That is an excellent essay on the film. Thanks.

“Replicants are robots” is an oversimplification. I’m surprised no-one has compared them to the kids in Lord of the Flies who loose empathy pretty quickly under their survivalist conditions.

I wonder if mechanical slaves (robots) who look like backhoes or coffee makers would get so much sympathy. If we put smiley faces with big eyes on rocks and give them sweet recorded voices, would we also have to give them the vote?

Blade Runner is a modern version of Frankenstein, another psychopathic killer, and provokes the same questions about humanity and about the dehumanizing influence of technology.

Sentient mechanical slaves should get the exact same amount of sympathy as any other slaves or as any other non-slave. Sentient slaves are bad. Just because someone looks different than you or was assembled in a different fashion is not a justification for enslaving them. Anyone who thinks it is a justification should take a hard look at their own capacity for empathy.

Thankful that others pointed out that the “slaves” are machines who have murdered and will continue to do so. Brutally. I, however am a fan of machines. Blade Runner is my favorite SiFi movie. I recommend you read the book. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep.

Not to be critical, but… The reviewer admits this was a first-time viewing, and the superficiality of the review is apparent. And the review is based solely on a viewing of the Final Cut. Having watched four different versions, dozens of times, over the past thirty-plus years, there are still things I discover every time I watch it. And there are tidbits even in the dreaded voice over version.

This movie was meant to be ambiguous. It was meant to raise questions. It was purposefully designed to be uncomfortable. It is not a 1950s, TV western, with good guys wearing white hats and bad guys wearing black. Deckard is a “good guy” who shoots women in the back. Batty is trying to cling to life while shoving his thumbs through his “father’s” eye sockets. Batty is growing and learning, and becoming “more human than human.” Deckard learns to be human, in the end, as well.

The reviewer empathizes with the replicants as slaves being murdered. They are just trying to survive in a society stacked against them. Zhora is doing a degrading job and has become part of society. That is too simplistic. She is a machine that has been programed (re-programed, actually) for political assassination. She is a danger. People might die by the machine’s hand if she is allowed to live. But, there is an ambiguity. Is she an immediate danger to humans? Maybe. Maybe not. Is she a potential danger to humans? Absolutely. Does she deserve to die? That is up to each individual viewer to answer for themselves. Ridley Scott will not provide the answer for you.

Are these replicants justified in killing humans because they are desperate to escape slavery? In some instances, they are acting in self-defense. Leon shoots Holden before Holden can kill him. But Roy Batty kills J. F. for absolutely no reason. J.F. is exactly like Roy. J.F. is an immature child, living alone with toys, trapped in a body that looks much older than he really is. Roy is a four year old in an adult’s body. Roy forces (enslaves) J.F. to do his bidding and then kills him when he is no longer useful. Roy’s treatment of J.F. is no different than society “retiring” replicants after they are no longer useful. Except replicants are dangerous. They are violent killers. J.F. is not a threat to Roy. All he can do is cower in fear while Roy murders Tyrell. He is too cowardly to even run away.

One of the most cussed and discussed aspects of Blade Runner is whether Deckard is a replicant. The view you hold can change the interpretation of events. There has been a lot of criticism of Deckard as a rapist in the love/rape scene with Rachel. If Deckard is human, I agree with interpreting his actions as rape, to some degree. However, if Rachael is a machine, and Deckard knows she is a machine, can it be rape? Can you “rape” a blow-up doll? If Deckard is a replicant, it becomes even more muddled. In the “voice over version” Deckard sits down to eat at a grimy road side café and says, “Shushi. That’s what my ex-wife called me. Cold fish.” That makes sense if he is a replicant. He has no emotions. He has not learned how to show his feelings to a woman. He is inexperienced. As he and Rachel grow and begin to develop feelings for each other, the newness makes them both clumsy. Deckard is a teenager fumbling to unlatch a bra for the first time. He does not know what to do, how to do it, or when a line is crossed. But, neither does Rachel. Is she trying to run away from Deckard because she fears him, or she fears new emotions that she cannot understand? Obviously, when Deckard pins her against the wall, Rachael is afraid. But, again, is she afraid of Deckard, or afraid of herself and these new, unknown emotions? When Deckard tells her to say, “Kiss me,” she does not say, “No. Leave me alone. Let me go.” Does she say, “Kiss me” because of Deckard’s physical threats, or is it something else? In the theatrical release, and in the European release, the “happy endings” make it clear that Rachael leaves willingly with Deckard. They both drive off together to a clean, open, uncrowded world, to share the rest of their lives together. In the happy endings, there is no hint of force, nor any indication that Rachael is an unwilling sex slave. In the European version, she says it is the happiest day of her life, and tells Deckard she loves him. He does not force those words out of her. She says them of her own free will.

The astonishing thing about Blade runner is that, thirty five years later, people still argue about it. Ridley Scott made a movie with no pat answers. He trusted an audience to think about issues he raised. What is it to be human? What violence can be justified? He made a movie with terrible violence and injustice. He made a movie where heroes are bad guys and bad guys are heroes, and then reverse roles as they grow. The characters are not static. They grow. Does it contain horrible, unacceptable, unjustified violence? Absolutely. But he made a movie with beautiful, heartbreaking moments. I have been married for thirty eight years now. When I was young and bulletproof, I thought I would live forever. My wife and I can now see a time when the tracks come to an end. In the theatrical, happy ending, Deckard says something that gains in relevance more and more for me with each passing year. He says, “Rachael was special. No termination date. I didn’t know how long we had together. Who does?” Wait until you get old, like me, and see how those lines play on your mind as you take your wife’s hand in yours.

The same goes with Batty’s final five lines. If there is a more beautiful five lines recorded on film, I have not seen it. And, again, now that I am old, I too have seen things. Moments that will be lost in time. If you cannot see the beauty in that speech, you must be a replicant.

I see another problem with this superficial review. The review only addresses the story. Blade runner is hardly only a story. To view it only in that way misses the impact it had on fashion, film, science fiction, musical scores, our collective view of the future, and so much more. Before Blade Runner, movies depicting the future were clean and sterile. The walls were clean. They didn’t even have pictures hanging on the walls. There were no dirty dishes in the sink. Food came out of machines as clean little manufactured cubes. There were heroes sailing through the stars. Buck Rogers. Captain Kirk. The Storm Troopers had spotless white uniforms. Blade Runner was dirt, pollution, rain, overcrowding. People were powerful, living in comfort, or powerless, living in squalor. Blade Runner changed the view that men would go from walking on the moon to conquering the stars, but instead, to barely getting by on a bowl of noodles in a dirty café on a claustrophobic street in a violent world.

There are reasons this movie has been discussed and re-discussed for more than thirty years. It is uncomfortable to watch. It is difficult to watch. But it does something. It leaves interpretation to the audience. It makes you question your own beliefs. It makes you question what you have just seen and experienced on screen. It is different from any movie I have ever seen. There are many other great movies. But how much can you discuss “Jaws”? “Boy oh boy! That was cool when he shot the scuba tank and the big fish blew up!” There are great, entertaining movies, with clean stories, good guys who make the bad guys pay in the end. Movies that answer all the questions. Blade Runner is not one of those movies. One viewing is not enough.

@@@@@ 24. rus

“it does seem like the point of the movie and the book and a whole lot of pkd’s work

what makes someone human?

what validates a life?

cue descartes”

thats what i thought as well

and yes like the OP noticed people seem to have made it about everything else to the point of being blithely dismissive of yes that question that runs through PKD body of work

i see how it makes people uncomfortable and the parallels to race it nudges and have wondered about peoples interest in scifi. The best scifi addressed(es) philosophy w regards to human psyche are they truly watching/reading just for the tech and gadgets? which makes it a bit sad.

@81 Very good question and I suspect the answer would be a resounding no.

Another question no one seems to want to address. Lets say I create a little mechanical toy in my workshop, by law I own that toy, I can give it to my grandson, I can sell it, I can even destroy it if I choose to do so. Ok now lets say I have the brains and skills and money to create a mechanical robot that not only looks and acts human but can think and feel like one, do I not have the same rights of ownership over it as I do the toy?

It’s true about fiction being a warped mirror, and anything looks familiar if you ignore all the things that make it different.

On one hand, the question of the replicants’ crimes is immaterial to their sentence. They’re not being killed because they’re dangerous or killed people; they’re being killed because they escaped. You are not meant to think this is just. The film is not subtle. Bryant is portrayed as a vicious thug, Tyrell as callous and insensitive. Batty’s death comes across as tragic, and Zhora’s as quite brutal. The opening cards call them slaves flat out.

On the other hand, it’s no good to excuse the replicants but not Deckard, or vice versa. Both are operating from a similar place: they can accept their circumstances and be killed, or they can kill to survive (which is what they all do). It’s hard to conscious why one is blameless, but the other is not. Both Deckard and the replicants could have chosen something else, but preferred to seek life, even if meant hurting and killing others. (Which, of course, ties into the film’s themes about immortality.)

And further complicating things is that the replicants really are dangerous. Not merely in the sense of possessing the capacity to hurt people (something that’s near universal), but in possessing the will and motive to do so. Which puts us in an awkward spot. The circumstances they’re in is hardly fair, but it’s not exactly right to say they can go around murdering people because life dealt them a (really) bad hand. This problem wouldn’t exist if there weren’t synthetic slaves, or possibly even if there were, but there was no standing kill order, but people often have to deal with bad circumstances they have little control over.

One detail that’s always bothered me, is when Deckard finds the snake scale, in the shower. A snake doesn’t have that type of scale (looks like a fish scale). They just have skin with a ” scaly” look.

@89 as I recall it is not a real snake, it is artificial so who knows how it was made.

An interesting series of ideas. We may have to decide pretty soon whether AI that is smarter than the smartest of us has a human profile, must conform to law. If so, then AI is not slave, nor master, but equal, and therefore accountable. It’s an important nuance going forward. The ’80s BR chose not equal, and accountable, so calling the replicants slaves is an interesting take on the film from our perspective in 2017 because it nicely contradicts how almost everyone felt about the film at the time. Judging past events by the present perspective ensures that those in 2052 who judge those from 2017 will draw equally different conclusions from us regarding our contemporary events. Which underlines how important it is to clearly state and situate “your referential” whenever you give your opinion.

Excellent review and puts words to feelings, impressions and thoughts that I could not put into words. My reaction to this movie has not changed and events today bear witness as to why. When I read about people being dragged from their cars by their hair, shot in their homes, murdered while in police custody, shot in the back while running and trying to get away from the terror they are feeling, all this resonates with the movie. Ever since I first saw this movie I have had ambivalent feelings towards Harrison Ford, his portrayal was so good that no matter the role I couldn’t disassociate. He always exemplified the complexity and ambiguity that lie

I think the author here misses the essential bit that Deckard is as much a slave as Rachel. They escape together.

90. sdzald

“@89 as I recall it is not a real snake, it is artificial so who knows how it was made”

But in Bladerunner “fake” creatures are supposed to be like “real” – isn’t that essential in the discussion we are having, about if replicants are human or not?

There’s probably a very good sequel to be written from the Replicant’s point of view!

The movie is not about slavery, or killing women robots; those are plot points. Bladrunner is purely existential, and asks a pretty straight forward question: What does it mean to be human? Still another question the movie poses is, “What is reality?”

Your essay was interesting, but I disagree with it.

I have read this post and some comments last week. Tomorrow i am gonna watch the new one so i have just watch Blade Runner again. Always loved the movie and i couldn’t really agree with all the negative view of Deckard and the ‘rape’ scene. He is a character in a bleak world doing a job he doesn’t like, but is good at, and he can’t get away from. Give him some credit.

He meets Rachel to whom he is attracted, feels guilt towards and genuinely wants to help. And who is a replicant. Not a human being. I think that this is what maked him act. With a real woman he never would haved made these steps. All this developes across different scenes.

I don’t know what a replicant feel and thinks, but i guess Rachel feels like shit. She thinks she worthless and needs protection. They both want change.

There is so much nuance in all the scenes. Of course it’s just my view, but It doesn’t do the film justice to just call it rape. He IS frustrated when she first doesn’t respond to him and he doens’t take no for an anwser (still don’t think he would do that with a real woman). He forces himself on her. And then something happens with Rachel and she willingly goes along with him. I don’t think she feels love but she does think it’s something she needs to do. Deckard wouldn’t have gone through with it if she still wouldn’t respond.

The next day she still lies in his bed and she’s ok with it. In the end they both gave eachother the change they needed.

I must say i’m not seeing Deckard as a replicant. Always seems more interesting to me.

@2 Zhora attacked Deckard first because she knew he was a blade runner who was there to kill her. Of course she struck first. He wouldn’t have simply left her alone if she hadn’t attacked him. No matter what, the blade runners wouldn’t have “never come near” Zhora and Leon and left them to peacefully pursue their jobs as snake dancer and factory worker.

@81 Frankenstein’s Creature isn’t a pysychopath; that word has a very specific meaning. In fact, he has a lot of empathy and outright says he didn’t enjoy killing Elizabeth or Henry.

I note the widespread perception that people who are going to be killed by other people do NOT have the right to kill those who have already signed off on their deaths. That’s — yeah, “awkward” is the polite term for it.

The central theme of the movie is a question about where humanity begins (in the context of artificial life). This review misses that entirely. Also, the version the author watched (I believe) contains the unicorn dream sequence, implying at the end of the movie that Deckard himself is a replicant. So in a way, it’s more like the masters pitting slave against slave. And why leave out any reference to the “Tears of Rain” scene where a replicant/slave demonstrates his humanity?

I’m also one of those supposed sci-fi fans who emerged from their cave to watch Blade Runner for the first time before BR2049. Sarah I hope you write an article on that too because I found it similarly hard to put my finger on why it was also such a strange and difficult film to really digest and have a definite reaction towards.

Both, for one, are SO slow moving (not in itself a bad thing), but what I really didn’t expect was how unobvious the messages were (again not a bad thing in this day of candy floss moralizing). But it’s as if the films opened the floor with the topics of “what is it to be human” and “how do we know if our memories are real?” plus a few others, but then left it at that. A bit too unsatisfyingly unanswered. A bit too much like real life in that we never get to answer any of the Questions, indeed that we don’t want to, that it is that very ambiguity we require as a distraction with which to amuse ourselves while we get on with the messy business of life and all its vices and all the people we knowingly or with ignorantly tread upon to secure our little islands of luxury.

Sarah, you liken the politics of the movie to the politics of today. I’d say there is a meta level where the way the film treats its core topics is the same way we treat ours. And that is powerful film-making to whoever can spot it.

This is such a beautiful and insightful review of the original film. I only want to point out one possible source of the central conflict between the replicants and the blade runners: the Tyrell Corporation’s monopoly power in he market for replicants. I wrote an entire research paper exploring this problem from a monopoly perspective here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1991411

This is perhaps the most brutally honest synopsis of the film I’ve yet read.

Yes, manufactured slaves. Illegal on earth because only off-world colonists (and the military) can have them. Presented to the world (movie audience included) as machines, yet they are developed genetically from an unknown “base stock” of what MUST be humans. Deckard has to verify that Zora (his first kill in the movie) is a replicant with a bone marrow test; machines don’t have bone marrow.

We know he’s done this before. He retired from the job…or tried to.

We don’t know why he quit. A revulsion to killing his own? Does he see them as human when no one else does? Is it the genuine risk that he’ll die doing his job?

As to the empathy test. I know some people right now who wouldn’t pass it. I think Ridley Scott had thought that through too. Hell, let’s be honest. Tyrell probably couldn’t pass that test.

Someone on Twitter used the word “cop” in connection with this movie in a way that made me think about the position of a Replicant on the police force, the way totalitarians use some members of an oppressed group to keep others in line. Deckard’s zeal in hunting down and destroying fellow replicants reminds me of minority group policemen who completely buy into the white-centric racism we’ve seen so much of recently.

Kudos to the review, by the way, for the force of its ideas. I don’t have to agree with every last detail of them to appreciate its insights.

@115 If Deckard is a Replicant, he doesn’t seem to know it.

Blade Runner is possibly my favorite film, though tomorrow I might say Apocalypse Now, but one of the reasons is that after 20 odd years watching it at least once a year, something in the film opened up to reveal another dimension that disturbed me as a person but delighted me as a student of story. What people ofter refer to as the ‘sex scene’ between Deckard and Rachel is nothing if not rape. The physical violence that begins it, her dawning realization that she had no choice, straight up rape. This made it clear that Deckard may be the protagonist of the story, but he’s not the hero. He rapes Rachel, shows no regard for any of the ideals of modern law enforcement, essentially murdering people in cold blood with zero proof that who he shoots was actually a replicant. Roy is the actual hero of the story. If you parse it down to the ‘hero’ being who’s actions are the most noble (noble being purely subjective, of course), Roy stands far above anyone else in the film. He shows all of the true human emotions that Deckard lacks: a love for his companions, compassion, remorse, and even mercy towards the man who murdered those who were, essentially, his family. Deckard on the other hand is pretty much a scumbag. I think this juxtaposition of traditional storytelling, and the fact that it’s missed by so many, is one of the main facets of Scott’s brilliance in this film.