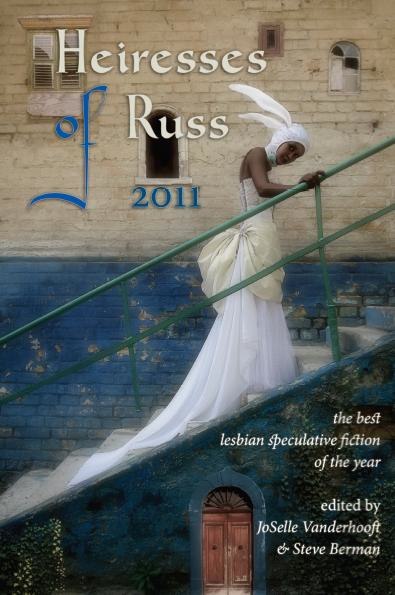

The inaugural installment of a series of books that will be collecting the best lesbian speculative fiction of the previous year, Heiresses of Russ 2011 is Lethe Press’s newest offering, a sister to the much-loved (at least around these parts) Wilde Stories collections. Heiresses of Russ 2011 collects the finest lesbian SF that was published in 2010 and includes such authors as N. K. Jemisin, Rachel Swirsky, Ellen Kushner, and Catherine Lundoff, among others. I was highly pleased by the table of contents and looked forward to being able to dive into the text. Plus, having a yearly anthology of queer women’s spec-fic in honor of the late, great Joanna Russ is pretty appropriate, and fills out the available spectrum of best-of books.

The guest editor for the 2011 anthology was JoSelle Vanderhooft, who has also worked on such books as Steam-Powered and Hellebore & Rue, and the co-editor was Steve Berman, the editor of the aforementioned Wilde Stories collections.

Vanderhooft says in the introduction that these stories are united by a theme of transformation, and I find that her description is completely apt: it’s a useful lens through which to read the following stories.

Story by story:

“Ghost of a Horse Under a Chandelier” by Georgina Bruce is the opener, a YA tale about two young women who are best friends and want to become more. But, it’s also about stories and what stories can do. “Ghost of ” is fabulously metafictional “I don’t want to be yet another dead lesbian in some stupid story. You can do better than this,'” says Joy’s ghost at one point, after the story has gone off track. It revolves around a magic book Zillah owns that changes every time she opens it, Joy’s comic book The Hotel, and their favorite lesbian superhero Ursula Bluethunder (“ a radical black, woman-loving superheroine, whose mission is to establish a lesbian separatist nation with money that she steals from banks using her superior intelligence, strength, and martial arts skills.”) Bruce’s tale is not only an entertaining, twisty piece of metafiction; it’s also touching, filled with moments that many readers will identify with, like looking for secret lesbians in history and literature texts, or wondering how you know when it’s all right to kiss your best friend. The narrative is light and well-crafted, rendering the jumps around in time and place perfectly understandable, and the prose is full of the infectiously engaging, sympathetic voice one often finds in great YA.

Jewelle Gomez’s “Storyville 1910” is a lengthy historical vampire tale set in New Orleans, dealing with issues of race and misogyny. While the message the story has is great, and the spectrum of characters in it is wonderful—especially the bits with the genderqueer performances of masculinity—the prose is somewhat uneven. There are moments of brilliance in dialogue, but the narrative relies too much on flat-out telling the reader details about the socio-historical setting instead of illustrating them evocatively. It’s an interesting take on the vampire mythos, and the world is well-realized—Gomez is a good writer, and this story was a decent read, but it’s not quite there yet for me.

“Her Heart Would Surely Break in Two” by Michelle Labbé is a short lesbian retelling of “The Goose Girl,” wherein the handkerchief is not lost as the princess drinks at the stream, but as she and the handmaid explore each others’ bodies and find their sameness under their clothes, before they trade roles. I quite liked it. The prose is a close cousin to poetry in this story; each sentence is built around sensory details and well-constructed.

Tanith Lee / Esther Garber (Lee writing as Garber)’s contribution is “Black Eyed Susan,” a story which I have reviewed previously here, and will revisit sufficiently to say that it’s handsome, eerie, and well-told, rife with Lee/Garber’s lush descriptions and precise dialogue. It was a favorite of mine from the Disturbed By Her Song collection, and remains a stunning story, playing with the potential reality of its supernatural possibilities while rendering them elusive at the same time. The focus on what it means to be other socially, ethnically, sexually in this story is subtle but pervasive, handled with wit and empathy.

“Thimble-riggery and Fledglings” by Steve Berman is another retelling, this time of Swan Lake, in which the story is as much concerned with a young woman breaking free of a patriarchal system to do her own world-exploring, to learn her own sorceries, and to become herself, as it is the romance between her and the swan-maiden. (The romance, after all, ends in a fickle betrayal of the sorcerous princess by her lover as her lover woos the prince.) The theme of transformations continues here in fine form as the story uses the imagery of birds, shapeshifting, and sorcery to explore ideas about identity and individuality. The angle the story takes on the classic tale is especially intriguing for those familiar with it.

I have spoken elsewhere, repeatedly, about how much I loved Rachel Swirsky’s novella “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window.” This story is an absolute necessity for a collection of the best lesbian spec-fic published in 2010; it’s certainly my favorite. “The Lady ” has an astounding level of emotional complexity and an unwillingness to take the easy way out of its ethical and moral quandaries. The prose is also phenomenal—Swirsky’s skill in constructing multiple worlds/settings out of the finest, most precise details is enviable and breath-taking. The range of themes, settings, and stories contained within this one novella is awesome in the real sense of the word. (It was also nice to see a lesbian story snag a much-deserved Nebula award.)

“The Children of Cadmus” by Ellen Kushner retells the myth of Actaeon, who gazed upon Artemis bathing and was turned into a stag, then hunted by his own dogs. The myth is still there, but the surrounding story fills it out with bittersweet purpose: Actaeon seeks Artemis for his sister, Creusa, who longs to escape the role of a woman in Greek society. His death is the price paid to bring the goddess to his sister, who has loved her. Creusa is also changed to a deer, but after the night has ended Artemis returns her to her human shape and asks for her service, which she gives willingly. The ending is at once satisfying—after all, Creusa has escaped being forced into bed with a man and has been able to devote herself to her love, erotic and otherwise, for the goddess—and deeply sad, as we are reminded of the price her innocent brother paid to bring the story to fruition. “The Children of Cadmus” is rich with poetic voice and imagery, and the new shape given to the old myth is immensely engaging.

Zen Cho’s “The Guest” is one of my favorite stories in Heiresses of Russ 2011. The characters are fully-realized, empathetic, and real, the magic is wonderfully strange, the taste of urban-fantasy to the tale makes it ever so intriguing, and Cho’s prose is concise in all the right ways. The dialogue captures a snapshot of the cultural and social moment the protagonist Yiling lives in that manages to be at once understated and completely clear about issues of sexuality, identity, and gender. The fabulous weirdness of a courtship between a cat and a woman that culminates in a partnership between them when the cat returns to woman-form is just right, and leaves a warm sense of pleasure behind once the story is finished. The matter-of-fact discussion of business, self-worth, and their new relationship that ends the story is the perfect closing scene. “The Guest” is a neatly parceled and expertly built story that does a great deal of narrative work in a small space; it was a delight.

“Rabbits” by Csilla Kleinheincz is a story originally published in Hungarian and translated to English by the author herself. It’s one of the more slipstream pieces, involving a decaying relationship in which one woman has been enchanted by a male magician and the other is fighting what seems to be a losing battle to keep her, while the ghost of their imaginary child slowly turns to a rabbit like Vera has on the inside. Kleinheincz’s prose is smooth and captures the strangeness of her subjects well; Amanda’s reactions and internal monologue are all believable and quite upsetting, as they should be.

Catherine Lundoff’s “The Egyptian Cat” is serviceable but not a favorite of mine; the story follows a thread that is quite predictable and includes one too many scenes that could be ticked off of a “paranormal romantic mystery” checklist. I was hoping at first that the prevalence of predictable characters, twists, and themes intimated a parody, but the story does seem to take itself seriously by the end. The characters are more engaging; the heroine is an editor of cat-related horror stories and has all the inner commentary one might want on the subject, for example. The prose is absolutely fine; Lundoff’s narration is quirky and often amusing. I simply wasn’t won over by the plotting.

“World War III Doesn’t Last Long” by Nora Olsen is a post-apocalyptic story in which one woman treks across New York to see her lover, though she’s been told to stay inside by the government programs because of potential radiation. The hints are heavy that the actual problem has more to do with government conspiracy than World War III, but the main story is her decision to risk going outside so she can tell Soo Jin in person that she loves her. It’s a short, sweet story with a nice background setting that Olsen puts together well with few details.

And finally, the closing story of Heiresses of Russ 2011 is “The Effluent Engine” by N. K. Jemisin. Jemisin’s story is exactly what I like in a rollicking spy-tale: political intrigue, twists and turns, and women with ambition, drive, and power doing really cool things. This story is set in the antebellum South in New Orleans, and the protagonist is a Haitian woman trying to find a scientist who can help her country get the edge on the French by creating a way to use the material produced from rum distillation. The commentary on race, power, gender, and sexuality in this story is complexly woven into the engaging, fast-paced plot; the end result is a tale that’s both gripping to the last and has something serious to say in its thematic freight. Jemisin’s handling of her subjects is deft, and the historical setting is well-illustrated for the reader without overuse of informational dumps. I loved it, especially the amusing and brilliant role-reversal at the end, wherein the shy Eugenie boldly takes hold of Jessaline for a kiss and declares that she’ll make enough money as a free scientist that she can set up house for them and let Jessaline retire from spying. That last scene is the perfect touch, keeping the story from the more stereotypical territory of the butcher, tougher woman seducing the femme and overwhelming her more delicate nature (hah); instead it posits them as equals in ambition and desire. Handsome prose, exciting characters, and crunchy thematic freight “The Effluent Engine” has it all, and shows that steampunk stories can do quite a lot with their scientific backgrounds.

Heiresses of Russ 2011 works well within its theme of transformations to put together a coherent, satisfying collection of lesbian SF published in 2010. While all of the stories had something good to offer, the highlights of the volume are Rachel Swirsky’s inimitable “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window,” Zen Cho’s “The Guest,” and N. K. Jemisin’s “The Effluent Engine.” The Swirsky is one of the best novellas I’ve read in years and more than deserves its central spot in Vanderhooft & Berman’s collection; Zen Cho’s story is concise, strange, and lovely, likely to stick with me thanks to its engaging characters, tantalizing hints of world-building, and fabulously weird lesbian courtship; and N. K. Jemisin’s fun, fast, thematically complex offering was the perfect close to the anthology.

The range of voices and takes on queer women’s subjectivity contained in this book are definitely worth mentioning, also: there are international stories, several works by writers of color, and a variety of generic categories represented, including historicals, YA, and steampunk. A large part of this collection is made up of mythical re-tellings, which are a perfect choice when considering stories about transformations and shapeshifting. The classic stories that these ideas came down to us in are worth revisiting with an eye to the potential queering of the past. The writers who have done so in their stories here did it with style, creativity, and a certain panache that’s required to make an old tale new again.

Overall, I was pleased with the theme and content of Heiresses of Russ 2011. It’s a great addition to the yearly best-ofs, gathering queer women’s voices in a way that the genre has needed for some while now. Lethe Press continues to press forward in publishing a larger and larger variety of queer SF each year, and this is one of my favorite additions to their catalogue. JoSelle Vanderhooft and Steve Berman have done a good job pulling this book together and making a perfectly coherent, readable whole out of 2010’s best lesbian SF. I look forward to the 2012 edition, and many thereafter.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.