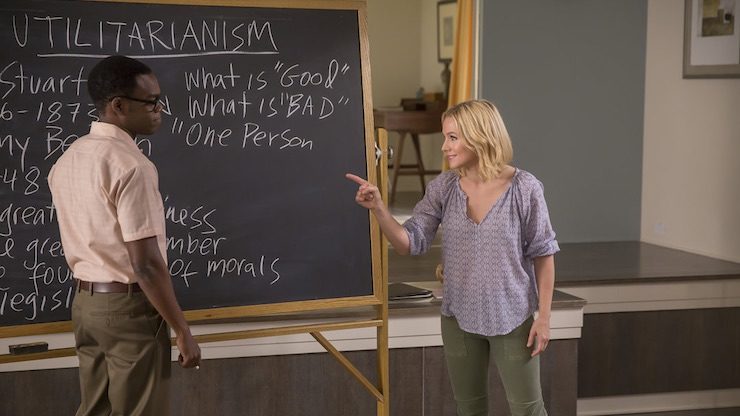

Everyone in the Good Place has lived an exceptional life — everyone, that is, except Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell), who arrives there seemingly by mistake after dying in a freak shopping-cart accident. She is, as she charitably describes herself, “a medium person,” but once she’s in the Good Place she wants to stay, so she enlists her soulmate Chidi to teach her how to be good and hopefully earn her place there. What makes The Good Place (just picking up from its mid-season break on NBC) so brilliant is the ways it explores the moral ramifications of this dilemma without passing judgment on anyone, even Eleanor. She’s arguably the villain of the story, yet we sympathize with her because she represents all of us “medium” people.

In the pilot, Michael (Ted Danson), one of the “architects” of the Good Place, explains that each person’s destination after death is determined by the sum total goodness or badness of every action of their entire life. Most of us can get on board with this concept, which makes no mention of belief in or allegiance to a deity. Eleanor herself listens to this explanation with equanimity, even as Michael goes on to explain that only the very best humans who have ever lived make it into the Good Place—not even Florence Nightingale qualified.

It’s only when Michael begins to recount Eleanor’s supposed accomplishments, like becoming a civil rights lawyer and visiting orphans in the Ukraine, that she realizes there’s been a mistake. Throughout the show we see snippets of Eleanor’s real life on Earth, which consist of taking a job selling fake supplements to the elderly, hurling abuse at Greenpeace volunteers, backing out of a dog-sitting commitment to see Rihanna perform in Vegas, and turning her roommate into a cruel meme and selling t-shirts with her likeness.

No one in their right mind would conclude that this adds up to a good life, but somehow Eleanor has no trouble believing she deserves admission to an afterlife not even Florence Nightingale was worthy of. Even when she realizes a mistake has been made, she has a hard time accepting that she is any less good than the legitimate inhabitants of the Good Place. As she drunkenly observes to Chidi, “these people might be good, but are they really that much better than me?” Of course they are; Chidi was an ethics professor, Tahani organized countless fundraisers for charity, and various secondary characters were tireless social justice crusaders. But Eleanor, in her humanness, sees her thoroughly terrible life as being nearly as good as theirs, even though her actions don’t support this. She becomes our belligerent proxy for the afterlife: she doesn’t belong there, but according to show’s version of cosmic reckoning, neither do we.

Because we come to solidly identify with Eleanor by the end of the pilot, we find ourselves invested in whether she gets to stay in the Good Place or not, which raises a whole slew of moral dilemmas (many of which Chidi breathlessly speeds through in his initial panic on finding out that Eleanor is an imposter). Does allowing a bad person into the Good Place damage its essential goodness? How good can it be for everyone else if some of its inhabitants aren’t up to the usual standards? At the end of the third episode we find out Tahani’s soulmate Jianyu, a Taiwanese monk, is actually a Filipino-American DJ named Jason who is not supposed to be in the Good Place, either. Both he and Eleanor try to keep their real identities a secret—but unlike Eleanor, Jason doesn’t have much interest in becoming good, so Eleanor and Chidi become his de facto handlers, corralling some of his more ill-advised impulses.

Eleanor also discovers early on that giving in to her less enlightened ideas causes problems for everyone; after she throws a tantrum at a welcome party thrown by Tahani, she wakes up the next day to a maelstrom of flying shrimp (she took all the shrimp from the hors-d’oeuvre tray), Ariana Grande songs (a result of her mangled attempt at pronouncing Chidi’s last name), giraffes (she called Tahani a giraffe), and blue-and-yellow pjs (her school colors). In addition to making everyone else unhappy, it comes dangerously close to blowing her cover. So Eleanor has a strong incentive to reign in her bratty behavior and try to get along with everyone—something she never did during her time on Earth.

One of Eleanor’s first self-imposed missions in the Good Place is to expose her beautiful and gracious neighbor Tahani as a fraud. Tahani is “too perfect”—she had to stop modeling because she’s “cursed with a full bosom,” she brings baskets of perfectly baked scones to everyone in the neighborhood, and as Eleanor grumbles at one point, even her hugs are amazing—so Eleanor assumes her goodness is a sham. She can’t stop comparing Tahani to herself long enough to realize the latter is trying to be her friend. Part of Eleanor’s insecurity also stems from a note slipped under her door that reads “You don’t belong here,” and she quickly seizes on the conviction that it was Tahani who wrote the note, despite the lack of any evidence or any indication that Tahani’s motives are less than pure. Tahani gives Eleanor a plant that becomes a barometer for their friendship: when Eleanor’s insecurities get the best of her and she refers to Tahani as a “bench” (swearing is literally impossible in the Good Place), the plant wilts and then later bursts into flame; but after Chidi coaches Eleanor into setting aside her insecurities and accepting Tahani’s friendship, the plant comes back to life and begins to flower.

One of the more intriguing questions the show raises is whether or not there can be mistakes in the afterlife, and implicitly whether Eleanor’s presence there is one of them. As Michael explains, the Good Place is made up of neighborhoods designed by supernatural beings like himself, called architects. Each neighborhood has its own physical and metaphysical rules, its own layout, color scheme, and weather. In a sense, each neighborhood is a tiny, self-contained universe. According to the rules Michael lays out, Eleanor shouldn’t be there; but Michael isn’t all-knowing, so it’s possible that the rules for admission to the Good Place are more nuanced than he believes; or, perhaps, that someone who hasn’t lived a good life can still be admitted to the Good Place for some higher purpose.

Eleanor enters the Good Place as the same not-great person she’s always been, but being surrounded by good people challenges her sense of identity and self-sufficiency in a way that never happened during her life. It’s almost as if Eleanor needed to die and enter the afterlife in order to have any chance at self-knowledge or redemption. As Chidi patiently explains, “knowing others is wisdom, but knowing yourself is enlightenment.” Of course Eleanor responds by making a masturbation joke, but she has already made progress toward thinking of other people as humans with desires and insecurities like her own. Her actions have consequences, even in the afterlife, and she starts learning how to consider those consequences and weigh their cost to everyone rather than just doing what she feels like in the moment. In spite of the fact that the show is set in the afterlife, in a way, the journey it’s been tracing thus far is a journey toward adulthood—not in the boring, bills-paying sense, but in the sense of gradually understanding that you are part of something bigger than yourself.

Ashley Wells writes about film for Fiction Advocate and Tribeca Shortlist. Besides movies, she enjoys cheese, Hearthstone, ancient Rome, and athletes being cute with animals. She lives in Brooklyn and you can find her on Twitter here.