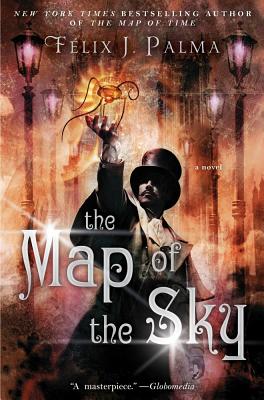

In the author’s acknowledgements appended to the end of The Map of the Sky, both Felix J. Palma and the translator in charge of rendering his whimsical worlds from the Spanish language text into English make mention of “the crushing loneliness of being a writer.” Though indubitably true, this is nevertheless an assertion utterly at odds with the non-stop narrative of the novel, which so entangles its central character H. G. Wells in the lives of others, and the affairs of a nation—nay, an entire galaxy!—that he scarcely has time to take tea.

That said, one imagines our man would far rather the solitude of the writer’s life:

“Herbert George Wells would have preferred to live in a fairer, more considerate world, a world where a kind of artistic code of ethics prevented people from exploiting others’ ideas for their own gain, one where the so-called talent of those wretches who had the effrontery to do so would dry up overnight, condemning them to a life of drudgery like ordinary men. But, unfortunately, the world he lived in was not like that […] for only a few months after his book The War of the Worlds had been published, an American scribbler by the name of Garrett P. Serviss had the audacity to write a sequel to it, without so much as informing him of the fact, and even assuming [Wells] would be delighted.”

The Map of the Sky unfurls with these words, which work overtime here at the outset of this massive melodrama to foreground Palma’s unabashed fondness for the self-reflexive—because Wells would surely object to this text, too—as well as setting its strange but (to a point) true story going.

In the several years since his sensational debut, following which Wells traveled in time to the automaton apocalypse of the year 2000, the writer has attempted to settle down—he continues to follow his creative calling and makes a wife of the love of his life—but when the publication of his new novel attracts attention from all the wrong sorts, history seems set to repeat itself.

Initially, Wells sits down with Serviss to excoriate the aspirant author for his audacity but, ever the gentlemen, he cannot quite bring himself to give the fellow what for. One liquid lunch later, the American sneaks his famous new friend into a secret room under the British Museum: a room indeed full of secrets, wherein the pair are aghast to espy, amongst myriad other marvels, a fin from the Loch Ness Monster, a flash of Henry Jekyll’s transformative concoction… and the dessicated corpse of a Martian.

“Wells had decided to accept as true the existence of the supernatural, because logic told him there was no other reason why it should be kept under lock and key. As a result he felt surrounded by the miraculous, besieged by magic. He was aware now that one fine day he would go into the garden to prune the roses and stumble on a group of fairies dancing in a circle. It was as though a tear had appeared in every book on the planet, and the fantasy had begun seeping out, engulfing the world, making it impossible to tell fact from fiction.”

Thus The War of the Worlds informs much of The Map of the Sky, in the same way as The Time Machine formed the foundation of Palma’s previous pastiche. Yet, this is but a glimpse of what is to come. Nearly 200 pages pass before our unnamed narrator cares to share the remainder of the alien invasion tale around which this novelty novel revolves, because—again in the mode of its successful predecessor—The Map of the Sky is a thing of three parts, and in the first, beyond the prologue’s tantalising tease, the author opts to retell another classic narrative.

These days, Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell is better known as the novella which spawned Howard Hawks’ The Thing From Another World—not to mention John Carpenter’s later, greater adaptation, nor the recent attempt at a revival of the franchise. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Palma conjoins the paranoid narrative threaded through the aforementioned iterations with the concerns of active Arctic exploration, such that The Map of the Sky‘s opening act rather resembles that Dan Simmons tome, The Terror.

At the behest of Jeremiah Reynolds, whose Hollow Earth theory has attracted the interest of various investors, the Annawan—captained by a fellow called MacReady, and counting amongst its crew a young Edgar Allen Poe—makes good time to the Antarctic, where Reynolds suspects the entrance to our world’s interior must be. But when the long polar winter begins and the ship becomes frozen in, they bear unwitting witness to the last voyage of a flying saucer, whose pilot—a monster able to assume the form of any of the stranded sailors—I dare say does not come in peace.

Eventually, the author ties elements of this opening act to The Map of the Sky‘s overarching narrative, yet I fear part one—for all that it’s a bit of fun—puts the book’s worst foot forward. The plucky panache of Palma’s elaborate prose is, alas, woefully unsuited to the atmosphere of unearthly terror he aims to recapture. There’s simply nothing insidious about The Map of the Sky‘s first act, surrounded as it is by such silliness.

But hey, two out of three ain’t bad, and The Map of the Sky regains lost ground when our lamentably aimless and still anonymous narrator returns to Wells, reeling from the realisation that “from the depths of the universe, intelligences greater than theirs were observing the Earth with greedy eyes, perhaps even now planning how to conquer it.” Here and hereafter the verve and vibrancy of Palma’s prose flows more appropriately; in this relaxed atmosphere, the author’s arch assertions do not stand apart so starkly; and though The Map of the Sky‘s characters are often comically cack-handed, they muddle through the alien invasion in a winning way.

In fact, in this section, and the book’s final third—which returns readers to a central perspective from The Map of Time—The Map of the Sky comes alive. There’s a whole lot of plot, but even as it accrues it’s exhilarating—relentlessly referential yet unerringly entertaining—meanwhile the sense and sensibilities of the ladies and gentlemen on whose padded shoulders rests Earth’s continuing existence endears deeply. In the interim, a blossoming love story is sure to warm your cockles, and the going is never less than lively because of the biting banter between certain stalwarts of the series.

Apart a shaky start, The Map of the Sky is a superb and eminently accessible successor to Palma’s last, sure to satisfy newcomers whilst appealing equally to returning readers. Come the cacophonous conclusion, one can only wonder as Wells does:

“He had written The Time Machine and then discovered he was a time traveler. He had written The War of the Worlds only to find himself fleeing from Martians. Would he become invisible next?”

Here’s hoping!

Niall Alexander reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for Tor.com, Strange Horizons and The Speculative Scotsman. Sometimes he tweets about books, too.