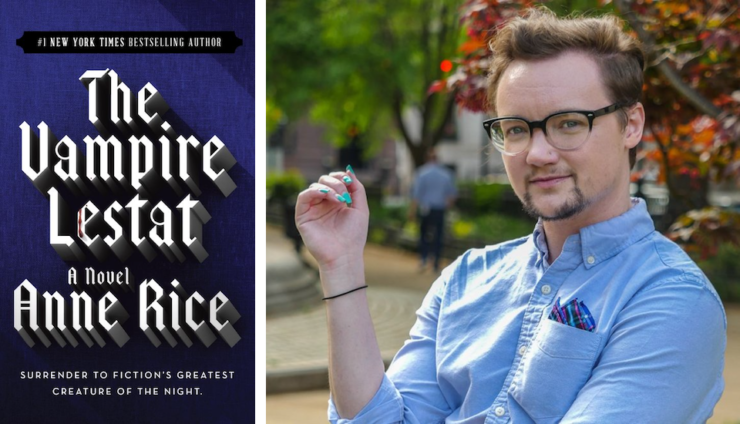

When I was a teenager, my mom gave me a book with a royal blue cover, raised silver lettering, and a spine so broken as to be almost illegible. A mass market paperback with yellowed pages that threatened to liberate themselves from the glue binding them and the distinct scent of old paper. Its outsides rich with phrases like “a voluptuous dream” and “unrelentingly erotic.” Its insides with blood and wine and teeth. With vampires.

I was probably too young to be reading Interview with the Vampire, but I devoured it and the seven other extant books of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles with only one lingering question: did my mom know how gay these books were?

She kept giving them to me—from her bookshelf. From beside the complete works of Michael Crichton and The Lord of the Rings books we’d attempted to read as a family, in advance of the movies. (We didn’t make it through The Two Towers, and can you blame us?)

Unlike our other books, Rice’s vampires were sexy, their world lush. The charismatic dandy Lestat and his emo boyfriend Louis traveled the world from New Orleans to Paris. They slept in the same coffin—they adopted a child together. I dog-eared scenes where the vampires Marius, Master of the household, and Armand, his beloved Amadeo, kissed and caressed—definitely naked and definitely in love.

I remember reading The Vampire Armand and thinking, is this allowed? I’d never read a book where men loved and made love to one another. Voluptuous and erotic, as promised. Did no one else know about this? Did my mother, a certified grown-up, know these books were full of gay vampire fucking?

Back in the late nineties and early two-thousands, I didn’t know any words besides “gay.” Not queer or bisexual or non-binary—any of the words I might use while attempting to describe Lestat de Lioncourt’s gender expression and sexuality, today. He was nebulous. Alluring. I wanted to be his Louis, to be Marius’ Amadeo. I didn’t know that was a thing I could sort-of be until after graduate school. Queer, that is, not a vampire, though, I’d have accepted the Dark Gift in a heartbeat. What was it if not a transformation? One that immortalized their bodies, gifting them supernatural abilities and beauty—I wanted that. I had no idea what to call it.

I’m sure my mother knew the contents of those books. They were used, after all, and she’d handed them to me, telling me generally what they were about. I knew she knew and still it felt like a secret.

Early in my transition, I bought a pack of men’s undershirts. I used to wear them underneath one of the two (women’s) dress shirts I owned and, after work, would unbutton the outer shirt, letting it hang open to expose the clean white cotton beneath. I never felt more masculine than walking through Baltimore City like that. No one else knew, I was certain. I wasn’t injecting testosterone, hadn’t cut my long curly hair, was wearing flowy women’s slacks and black flats.

I was an innocent blue book with Gothic lettering and high-profile blurbs. A mass market paperback, like you might find in the grocery store. I interacted with respectable people, worked in an office with cubicles and a pod coffee maker. I was not a man; my pages did not contain monsters.

That was my secret: like The Vampire Chronicles, no one knew I was gay on the inside.

I did eventually tell my family and friends, did begin those hormones and buy a whole new wardrobe—a shopping spree that would’ve made Lestat proud. Even though I was supposedly freer, the loss of my secret came with restrictions. I had to answer questions. Justify myself. If I was a guy, why was I wearing a long feminine necklace? Was there a reason I decided to wear an undershirt? I couldn’t just wear it, anymore. No one asked my dad why he wore an undershirt and the answer was I didn’t have one. I wore it because that’s what men did and it made me feel masculine.

Because I fucking wanted to.

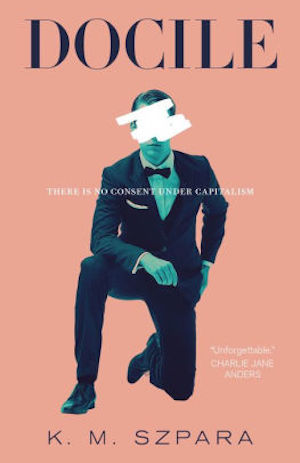

Buy the Book

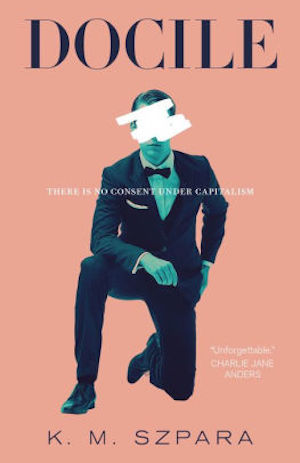

Docile

I didn’t encounter any other queer literature outside of fanfiction for almost a decade. I didn’t know it was harder to publish or where to look for it because, like many readers, I heard of good books from friends or browsing Borders (may it rest in peace) or Barnes & Noble. Most of my friends weren’t queer—I didn’t know I was queer until after I finished writing my first novel (gone but not forgotten).

Working on it, I didn’t know what queer literature could look like. I’d forgotten Anne Rice; all I remembered was fanfiction. I wrote what I thought gay fantasy was supposed to look like—a slow burn with unresolved sexual tension and some chaste making out at the end. Nice soft gay content that follows the same trajectories as many novels I’d read since high school. I put it aside because something was missing. Something with teeth.

I wrote—a new book that was lush and thorny and queer like I remembered of Lestat’s world, but flushed red with what I’d learned from fanfiction. That no trope was sacred. That they didn’t have to wait until the end to kiss; they could fuck in the first chapter, if I wanted them to. I was Akasha, Queen of the Damned, the one from whom all the blood flowed. I had power over my words and myself and my genre.

Years later, I no longer wear undershirts. I stopped once I bought dress shirts from the men’s section, no longer needing a secret to feel validated. I don’t even identify as particularly masculine or A Man unless I’m updating my driver’s license or using a public facility. I use words like queer and femme. I read books with covers that betray their luxurious gay interiors. Write about angry trans vampires who have a complicated relationship with blood. Traumatized debtors who have complicated relationships with trillionaires. Gatekeepers and virtual realities and quests—and they are all queer. They are all me.

When I was reading them for the first time, you couldn’t find Vampire Chronicles fanfiction on the Internet because, as I read on a message board, Anne Rice didn’t approve of it. I never got to write those stories, but that’s okay because I wrote mine. After devouring hers—after desiccating like a vampire who hadn’t fed for a decade. When I wanted more, I didn’t wait for the Dark Gift. I wrote my own.

Hugo and Nebula finalist K.M. Szpara is a queer and trans author who lives in Baltimore, MD. His debut novel, Docile, is coming from Tor.com Publishing in 2020; his short fiction and essays appear in Uncanny, Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, and more. Kellan has a Master of Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School, which he totally uses at his day job as a paralegal. You can find him on the Internet at his website and on Twitter at @kmszpara.