A story describes a world. Of necessity, it can only describe part of that world—but we can see the rest of it out there, full of sights and scents and scenery not entirely like but not entirely different from that which is familiar.

A story has a beginning and an end, but those aren’t always—or even often—the beginnings or ends of lives, of longer narratives, of things carried on and carried over, picked up and rejected, chosen and regretted.

A story, as we know, can be just one place to start. We are experiencing, for better or worse, a prequel boom. Mostly it’s on TV, but many of those stories come from (or spill over into) books. And the more of them I watch, the more I wonder: What do we want from prequels, anyway? What are we looking for when we turn back the clock in Westeros, in Middle-earth, on the USS Enterprise and in that galaxy far, far away?

Spoiler warning: There are some slightly vague details about The Rings of Power‘s season finale towards the end.

To tell you the truth, I thought about prequels for days before I remembered that, technically, Star Trek: Strange New Worlds is one. This may be the simple effect of my Star Trek knowledge, pre-Discovery, being almost entirely limited to the movies (and my ninth grade math teacher showing us “The Trouble With Tribbles” to illustrate exponential growth). But it’s also, I think, because there is a direct and immediate connection through the characters. It feels less like a prequel and more like a chapter that we just skipped before. We only take one step backwards—not a century, not even a generation. Just a moment. In a way it’s like that Buffy episode where we go back to her at her previous high school, with a previous Watcher, with Angel stalking her from a car. It just lasts much longer.

Strange New Worlds isn’t trying to convince us of connections that aren’t there, or explain the behavior of characters years down the line. It’s showing us where one very famous relationship began, but it’s also giving us very good reasons to be invested in other relationships around Spock and Kirk. That show can’t work without Captain Pike, without the tensions and affections among his crew. It understands that Spock and Kirk didn’t become Spock and Kirk in a vacuum, that they were shaped by the people around them and the experiences they had—and so it builds into that space, into those question marks.

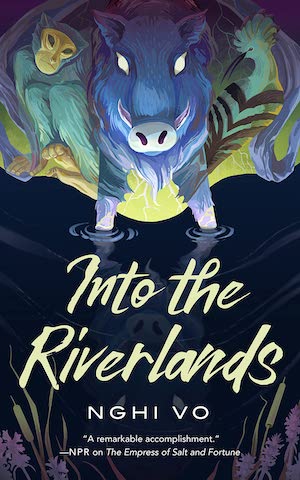

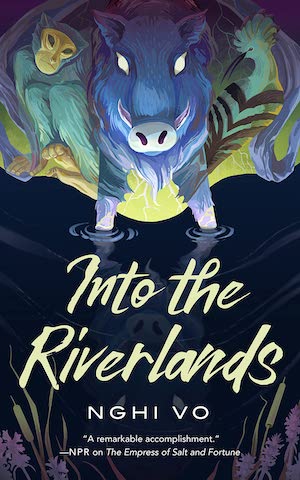

Buy the Book

Into the Riverlands

A good prequel is more questions than answers. Andor has one very solid, looming answer at the end of its story: Cassian Andor dies in Rogue One. There is no getting away from this outcome, but there is the simple fact that when he dies, we know all too little about him. He’s a bundle of questions that Tony Gilroy’s show is taking its time to answer; halfway through the first season, we’re only beginning to grasp how this man winds up sacrificing himself for the Rebellion. But around that, we have to contend with the Empire he’s up against: the fat-cat brass who barely see a given planet’s natives as people; the by-the-book cop who gets in over his head; whatever it is Denise Gough is playing (I really want to know); the tricky maneuvering of people in and closer to power.

Star Wars is, across media, notably good at prequels that don’t feel like prequels. Say what you like about George Lucas’s prequel trilogy—and trust me, I have many things to say—but it rarely feels like it is straining to explain things about Anakin Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi. Instead, it explores who they were to each other, and to those around them, and how that all fell apart as Anakin, traumatized and jealous and needy, was tempted by the Dark Side. The Clone Wars does this even better, eschewing pat explanations for carefully built relationships and situations, struggles and divisions. And Rebels arguably does it even better yet, spinning off a found-family story that only very slowly begins to inch toward the greater canvas with which we’re familiar.

This is often true in Star Wars books, too: They explore moments in character’s pasts which illuminate who they are without offering too-tidy explanations for how their specific characteristics came to be. Master and Apprentice is a character study about the relationship between younger Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon. Leia, Princess of Alderaan imagines a teen Leia (and if you’ve read it, it’s hard to watch the young Leia in Obi-Wan Kenobi without thinking of the teenager she’ll be before long). Ahsoka is a sequel or a prequel, depending on your point of view, and it hones in on her character with a focus we’d never otherwise get to see.

But the thing these stories have in common is the thing they share with Strange New Worlds: They’re only years or generations apart. They are not trying to stretch threads across centuries, let alone millennia. Two hundred years is a brief enough period that echoes from one story may convincingly appear in another. Narrative threads and tropes and callbacks and references that stretch thousand years, on the other hand, can be a direct hit to the suspension of belief.

Every viewer, of course, is going to find something different to love or be annoyed by in a show. Frankly, it is annoying me that I find House of the Dragon to be a more solid series than The Rings of Power, the latter being the one in which I would much prefer to be invested. But where Rings has to work around thousands of years and a tangle of rights issues to tell its story, House has only to walk a tricky line between being Game of Thrones Part II and being its own monster.

If it feels too much like more of the same, that may be less because it’s a prequel, and more because everyone in Westeros is terrible and moments of grace are all too few. House of the Dragon knows that we’re starting with a certain amount of info: That the Targaryens are a dramatic disaster family, full of dragons and drama and incest and infighting; that the Iron Throne is a dangerous place to sit; that all anyone seems to have to do with themselves in this world is scheme, bicker, and murder (sometimes with a side dish of expository sex or gratuitous violence). And so instead of trying to tell a different story, the show tells the same story but with different characters. It could, perhaps, use more characters we can get a little bit invested in, but if you want scheming and bloodshed, it certainly delivers. And it does so without trying to draw too-neat threads to those characters who will show up 200 years down the line. We know the names and the haunted castles, and that’s enough.

But what to make of The Rings of Power? I wanted to love this show. I was a Tolkien-obsessed child, albeit one who could never make it through all the appendices. (I tried and tried!) I wanted narrative, not history. So I am not the person to tell you exactly what happened when and which details the showrunners are creating from whole cloth. (Thankfully, we have Jeff LaSala for that.)

But I am a person who looks at this show and thinks: Did it have to be like this? Did everyone have to have a tidy little motivation and a parallel in the Third Age, the stories we know? Will I ever forgive the show for the suggestion that Isildur’s horse went to go find him, just like his descendant Aragorn’s horse did in the Peter Jackson movies a zillion years later? Would I have put an iota of thought into the question of whether one of these characters was Sauron if there had been anything else to talk about? Is that really all it took to trick Celebrimbor into forging the rings?

One thread of the many tangled up in this show is a thread that is really about character, and it’s the story of Elrond and his bestie Durin and Durin’s most excellent wife Disa. It inches up to wanting to explain “and this is why Legolas and Gimli are Like That!” but these characters pull it back every time, locating the real differences between elves and dwarves (dramatically different sense of time and humor, for one) and finding ways to illustrate that via personality. This isn’t giving little harfoot Nori a very Sam-like friend, or doing some really strange things with the orcs. It’s remembering that a prequel is a story about people we haven’t met yet—or that we only know later. I can believe that Elrond was once an awkward messenger boy between his king and that of the dwarves far more easily than I can believe that Sauron played a “just rule by my side” move with Galadriel and then left her in a stream.

What I wanted from this show was to see a different time in Middle-earth, not to see repeated images and forced connections. (Why is the Balrog there?!?!?) It feels like a story that’s fighting itself, trying to do too many things at once and never letting us settle in with anyone—and fighting the inevitable comparisons with Jackson’s trilogy while also leaning hard into creating resonance with those familiar images.

What do we want from any of these stories? Is it the comfort of the familiar, just slightly changed? It is for the world to get bigger, and all of us little harfoots venturing out to see more of it? Is it a new perspective on a familiar tale? The first prequel I ever recognized as such was Wicked, which at first got my hackles up and then became one of my favorite books. It doesn’t explain how the Wicked Witch of the West came to get murdered by Dorothy Gale; it explores who she was, and what the world that made her was like. (One doesn’t wind up in an isolated castle with a bunch of flying monkeys because one was having a good time of it.)

I want a prequel to show me something I didn’t expect, or give me a new understanding of something I loved or hated. I want it to push the boundaries of the world, or show me that the world wasn’t entirely how I understood it. (I have mixed and vague memories of The Magician’s Nephew, but it certainly changed my view of Narnia.) I want it to feel like a story that needed to be told as much as the previous tale did—not, as Vulture’s Kathryn VanArendonk so perfectly put it, like “efforts to make and remake things that were already successful and serve them to audiences again, like last night’s roast chicken turned into today’s chicken salad.”

What do you want from a prequel?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.